Adjusting a pneumatic flow control valve isn't just about turning a knob clockwise or counterclockwise. It's about understanding the thermodynamic behavior of compressed air, the friction characteristics of cylinder seals, and the critical difference between meter-in and meter-out control strategies. In industrial automation, where a 100mm bore cylinder at 0.6 MPa can generate nearly 4700 newtons of force, improper adjustment can result in damaged equipment, wasted energy, or even safety hazards. This guide provides step-by-step procedures grounded in fluid mechanics principles and field-proven troubleshooting methods.

Understanding Pneumatic Flow Control Valve Types

Before making any adjustments, you must correctly identify the valve type installed in your system. Misidentification is the primary cause of cylinder malfunction in pneumatic circuits.

Unidirectional vs Bidirectional Flow Control Valves

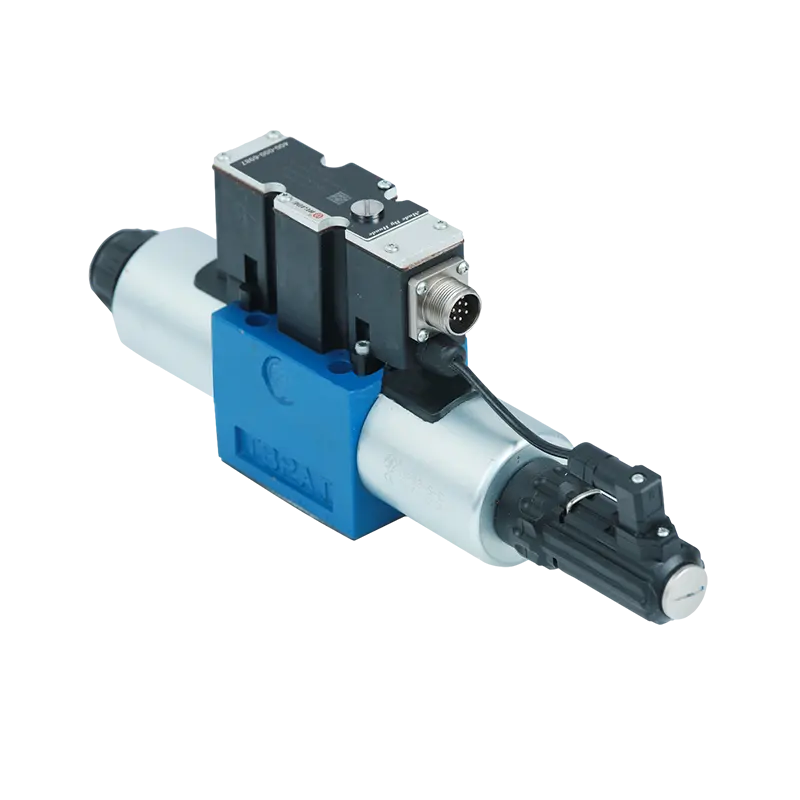

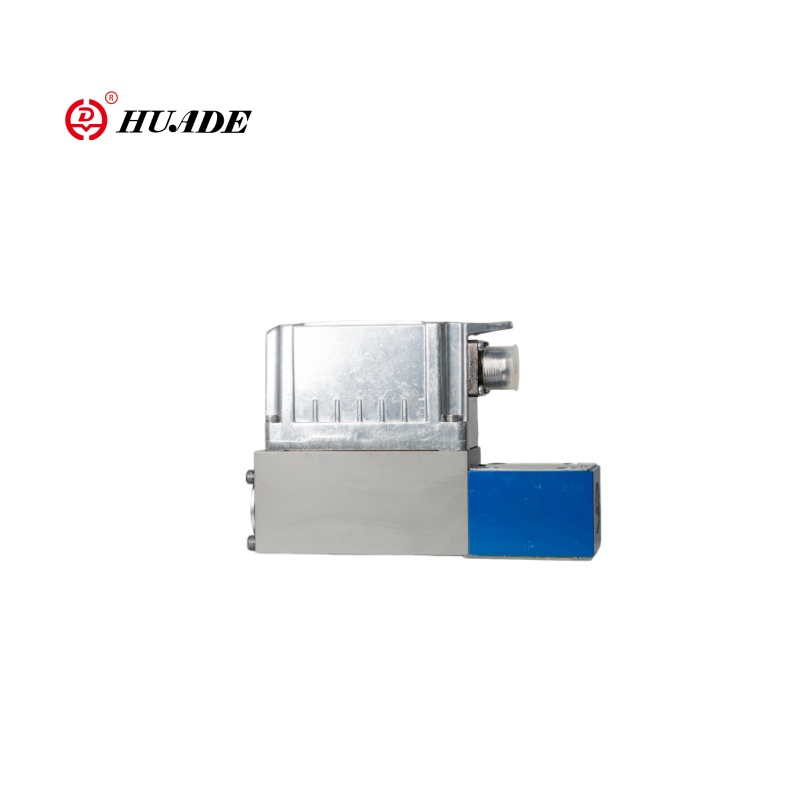

Most industrial speed control applications require a unidirectional flow control valve (also called a throttle check valve), not a simple bidirectional needle valve.

Unidirectional Flow Control Valve Structure:

Contains two parallel flow paths. The metering path uses an adjustable needle valve to create controlled restriction, while the bypass path contains a check valve that opens for reverse flow, allowing unrestricted fast return. This design allows the cylinder to move slowly in one direction (controlled extension) while returning quickly in the opposite direction.

Bidirectional Flow Control Valve:

Restricts flow in both directions equally with no internal check valve. When misused for cylinder speed control, it prevents rapid pressure buildup on the inlet side, causing weak cylinder startup and potential failure to overcome static friction (stiction).

| Feature | Unidirectional (Throttle Check) | Bidirectional |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Structure | Throttle orifice + check valve (parallel) | Throttle orifice only |

| Flow Resistance | One direction restricted, reverse free-flow | Both directions restricted |

| Typical Application | Cylinder speed control (meter-in/meter-out) | Air motor speed control, constant damping |

| ISO Symbol | Includes check valve symbol | No check valve symbol |

Installation Position: Port-Mounted vs In-Line

Port-mounted (banjo type) valves screw directly into the cylinder port. This minimizes dead volume between the valve and piston, providing faster pressure response and better motion rigidity. The downside is difficult access in compact machinery.

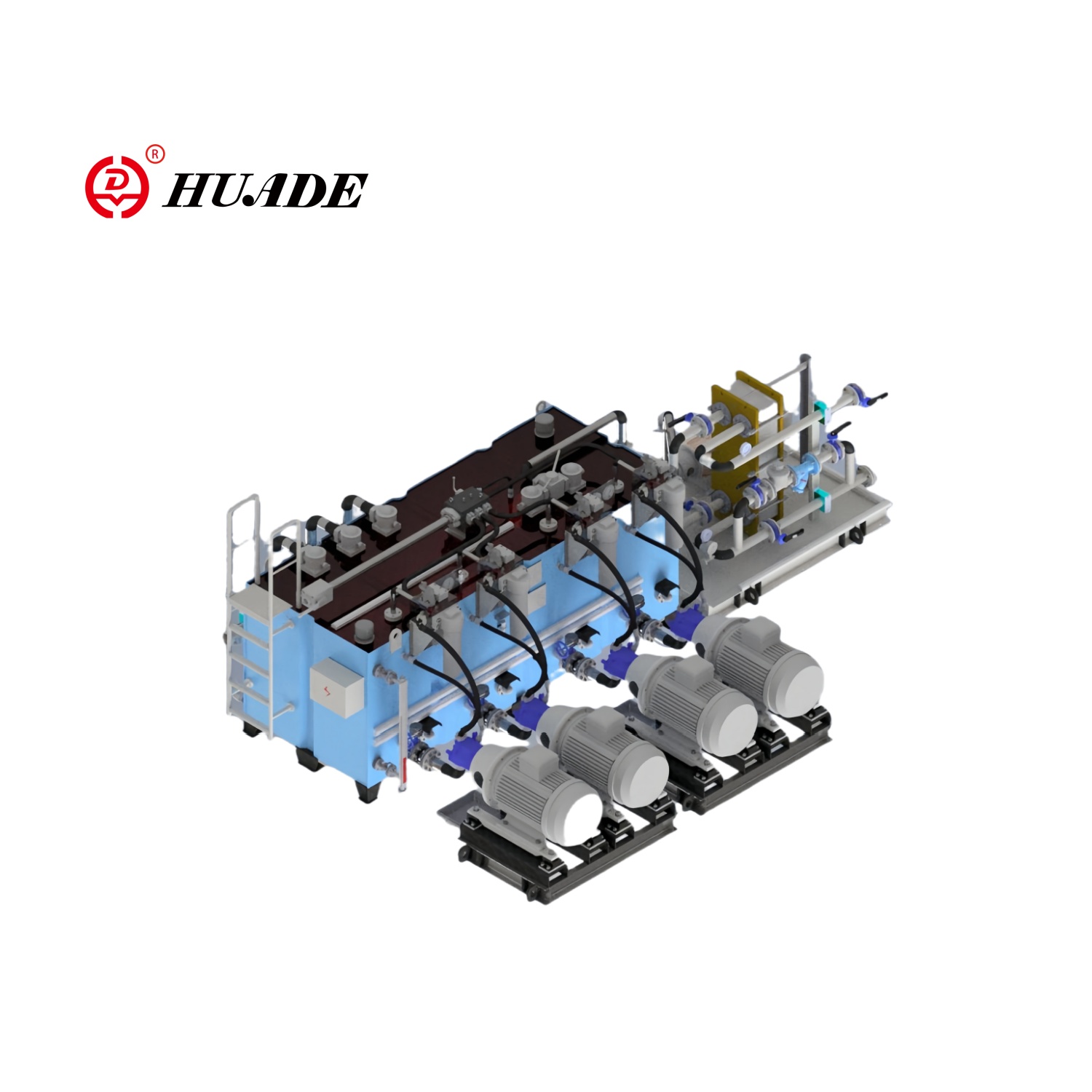

In-line valves install in the pneumatic tubing between the directional control valve and cylinder. They offer convenient centralized adjustment but introduce a "capacitance effect" problem. Long flexible hoses expand under pressure, storing air energy. This causes spongy response or oscillation at the end of stroke, particularly noticeable in meter-out control configurations.

Meter-In vs Meter-Out: Choosing the Right Control Strategy

The fundamental decision in pneumatic speed control is where to place the throttle valve: on the inlet side (meter-in) or exhaust side (meter-out). This choice determines not just how the cylinder moves, but how stable it moves under varying loads.

Meter-Out Control: The Industrial Standard

In meter-out control, the flow control valve is installed on the exhaust side of the cylinder. The inlet side uses the check valve bypass for unrestricted full-flow charging.

The piston reaches force equilibrium between inlet pressure and exhaust back pressure. This back pressure acts as a high-stiffness "air spring" or pneumatic brake. It makes the cylinder insensitive to load variations, prevents free-fall in vertical applications, and effectively suppresses stick-slip crawling.

Meter-In Control: Limited Application Scenarios

In meter-in control, the throttle valve restricts air entering the cylinder while the exhaust side vents directly to atmosphere with no restriction.

Since there's no exhaust back pressure, once the piston breaks through static friction (which is typically 2-3x higher than dynamic friction), the net force becomes excessive. The piston suddenly accelerates forward (lunges). As volume expands rapidly, inlet pressure cannot keep up and drops, causing the piston to slow or stop until pressure rebuilds. This cycle repeats, creating severe stick-slip oscillation.

| Application Condition | Recommended Strategy | Physical Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| General horizontal push/pull | Meter-Out | Provides optimal speed stability and load disturbance rejection |

| Vertical load (downward motion) | Meter-Out (mandatory) | Prevents gravity-induced free-fall and runaway conditions |

| Single-acting cylinder | Meter-In | Physical limitation - no reverse chamber for exhaust throttling |

| Micro cylinders / small bore | Meter-In | Exhaust chamber volume too small to establish stable back pressure |

| Energy efficiency priority | Meter-In | Eliminates back pressure power loss (trades control quality) |

Safety Protocols Before Adjustment

Projectile Hazard: Many older valves lack internal retaining clips. Over-loosening under pressure can eject the needle like a bullet. Never position your face in line with the valve axis.

Gravity Drop Hazard: For vertically mounted cylinders, over-loosening the exhaust throttle essentially removes the "brake," causing instant load drop. Physically support all vertical loads before adjustment.

Residual Energy: Even after shutting off air supply, high-pressure gas remains trapped. Use a dump valve to exhaust all residual pressure before any disassembly.

Pre-Adjustment System Health Check

Confirm the system is in an adjustable baseline state before turning any screws. Check air supply pressure (typically 0.4-0.6 MPa), verify air quality (oil sludge blocks orifices), test for leaks (which defeat meter-out control), and ensure mechanical freedom of the load.

Step-by-Step Adjustment Procedure

This standard operating procedure (SOP) achieves smooth, controlled, and efficient motion control.

Step 1: Initial State Setup - Full-Closed Principle

Many beginners leave valves in factory condition (fully open) before applying air, causing destructive slamming. Instead, turn both extend and retract screws clockwise until gently seated (fully closed), then back out 1/4 to 1/2 turn. This ensures minimal air flow for safe initial actuation.

Step 2: Coarse Adjustment

Connect air supply and execute manual jog operation. The cylinder should crawl extremely slowly. Locate the valve controlling extension exhaust and turn counterclockwise slowly (max 1/4 turn at a time) until speed reaches ~80% of target. Repeat for retraction speed.

Step 3: Fine Adjustment

Eliminating stick-slip crawling: If motion is jerky, slightly loosen the throttle to increase speed above the stick-slip threshold, or increase system pressure to improve air spring stiffness.

Balancing strokes: Adjust non-working return strokes to the maximum speed that produces "no audible impact sound" to reduce cycle time without damaging components.

Step 4: Locking and Verification

Tighten lock nuts with a wrench. Warning: Micro valves (M5 ports) require only 0.5-1.5 N·m torque. Excessive torque shears threads. Always run several test cycles after locking to verify the setting didn't drift.

Understanding and Adjusting Cushioning

Flow control valves (speed) and cylinder cushion needles (deceleration) are two completely independent systems that must be adjusted in coordination.

Ideal Cushion State Adjustment - The "Traffic Light" Method

The goal is for the piston to reach exactly zero velocity at the instant it contacts the end cap.

- Over-damped (Yellow Light): Cylinder stalls at the end or bounces. Correction: Turn cushion needle counterclockwise.

- Under-damped (Red Light): Metallic "clack" sound and vibration. Correction: Turn cushion needle clockwise.

- Critical Damping (Green Light): Piston runs at full speed, decelerates smoothly, and stops silently. Action: Lock position.

Critical Note: Whenever you change speed settings or load weight, you must re-adjust cushioning. Since kinetic energy scales with velocity squared ($$E_k = \frac{1}{2}mv^2$$), your previous cushion setting becomes invalid.

Troubleshooting Common Adjustment Problems

Problem: Setting Drift

Symptom: Speed changes throughout the day.

Causes: Machine vibration loosening the needle, or temperature changes affecting lubricant viscosity.

Solution: Use low-strength threadlocker or valves with damping rings; perform warm-up runs.

Symptom: No speed change, then sudden jump.

Solution: Always reach the setpoint through the "tightening" direction to eliminate thread clearance influence.

Symptom: Cylinder moves too fast even with valve closed.

Causes: Internal check valve seal failure (bypass leakage) or oversized valve selection.

Solution: Replace with smaller port diameter valve.

Maintenance and Lifecycle Management

Pneumatic valves are wear items. Internal O-rings and seal pads harden over time. In high-cycle applications (>1000 cycles/hour), inspect valve sealing annually and perform preventive replacement every two years.

Contamination Control: PTFE tape fragments are a common issue. If tape debris enters the line, it jams the needle gap. Use pre-sealed fittings or leave the first thread exposed when wrapping tape.

Conclusion: Adjusting pneumatic flow control valves combines theoretical physics with hands-on engineering judgment. Select the correct unidirectional valve, prioritize meter-out control, follow the "closed-crack-coarse-fine-lock" procedure, and coordinate speed with cushion adjustments.