When you look at a hydraulic or pneumatic schematic for the first time, those boxes, arrows, and lines might seem like an indecipherable code. But directional control valve (DCV) symbols are actually a precise visual language that tells you exactly how fluid flows through a system. Whether you're a maintenance technician troubleshooting a production line or an engineering student studying for exams, learning to read these symbols correctly can mean the difference between a smoothly running machine and costly downtime.

The Foundation: What Directional Control Valve Symbols Actually Represent

Directional control valve symbols follow the ISO 1219 standard for hydraulic systems and ISO 5599 for pneumatic systems. These aren't just arbitrary drawings—each element of the symbol carries specific functional information.

The basic building block is the square envelope or box. Each box represents one discrete position that the valve spool can occupy inside the valve body. If you see two boxes side by side, that's a two-position valve. Three boxes? That's a three-position valve with a center or neutral state.

Inside these boxes, you'll find arrows and T-shaped lines. Arrows indicate flow paths—they show which ports are connected and the primary direction of fluid movement. The T-shaped symbols (sometimes just a perpendicular line) indicate blocked ports where no flow can occur in that particular valve position.

Here's the critical concept many people miss: when reading these symbols, you need to imagine the boxes sliding horizontally while the port connections stay fixed. When the valve is actuated (say, an electromagnet energizes), mentally shift the entire symbol so the activated box aligns with the port labels. The internal arrows and blocks in that box now show you the new flow pattern.

Decoding Valve Nomenclature: The x/y Format

You'll often see valves described as "3/2 valve" or "4/3 valve." This shorthand tells you two things instantly:

- First number (x): Number of ports (connections to external piping)

- Second number (y): Number of positions (switching states)

A 2/2 valve has two ports and two positions—typically used for simple on/off control like opening or closing a single-acting cylinder. A 5/2 valve has five ports and two positions, commonly used in pneumatic systems to control double-acting cylinders with separate exhaust paths.

| Valve Type | Ports | Positions | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2/2 | 2 | 2 | Single-acting cylinder control, on/off isolation |

| 3/2 | 3 | 2 | Single-acting cylinder with return spring |

| 4/2 | 4 | 2 | Double-acting cylinder, simple extend/retract |

| 4/3 | 4 | 3 | Double-acting cylinder with neutral center position |

| 5/2 | 5 | 2 | Pneumatic cylinder with independent exhaust control |

Hydraulic Port Identification: The Letter Code System

In hydraulic directional control valve symbols, ports are marked with letters that indicate their function in the energy circuit.

Standard Working PortsPort P (Pressure): This is where high-pressure oil enters from the pump. It's the energy input. In symbol analysis, whether P is blocked or connected to other ports determines the entire system's unloading strategy.

Port T (Tank): The return line back to the reservoir. This is typically low pressure, though excessive back pressure at T can affect valve shifting and should be monitored.

Ports A and B (Work Ports): These connect to your actuator—the cylinder or motor doing actual work. Standard convention is that when P connects to A, the cylinder extends. When P connects to B, the cylinder retracts.

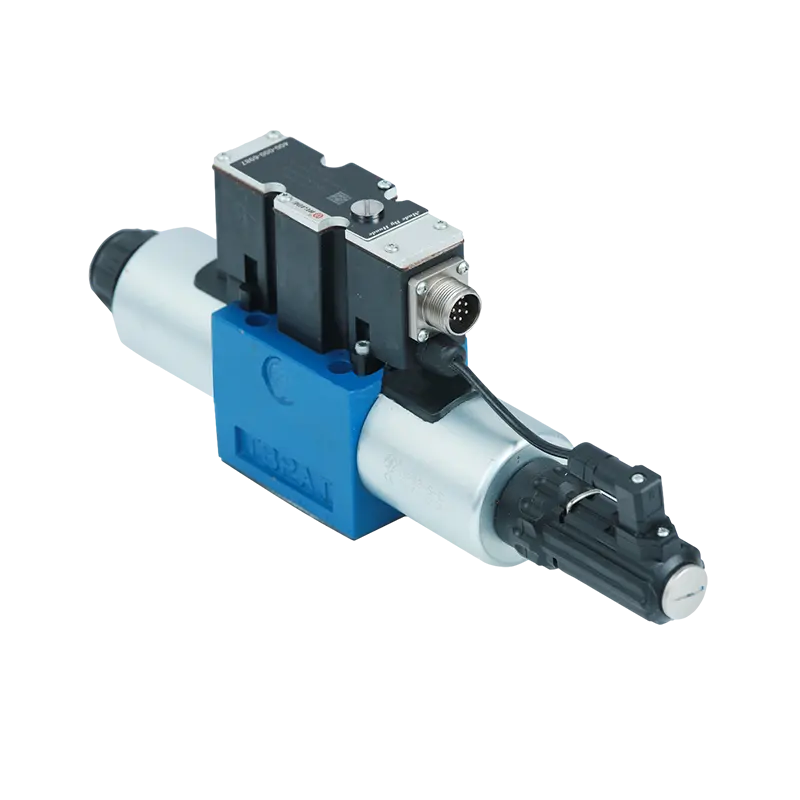

Port X (External Pilot Supply): When you see an X port, you're looking at a pilot-operated valve. The main spool is too large to shift with just an electromagnet, so it uses hydraulic pressure to move. X provides this control pressure from an external source.

Port Y (External Pilot Drain): This separate drain line for pilot oil prevents problems when the main T port has high back pressure. If pilot return oil had to push against 30 bar of back pressure, the solenoid might not generate enough force to shift the valve.

Port L (Leakage Drain): Appears mainly in motor symbols or some spool valve configurations. It drains internal leakage from the spool clearances back to the tank to prevent pressure buildup that could blow out seals or damage the valve body.

Actuation Methods

Symbols indicate not just what the valve does, but what causes it to shift. These are drawn on the sides of the boxes.

- Solenoid (Rectangle with diagonal line): Electrical actuation.

- Spring (Zigzag line): Returns the valve to neutral or a specific position when power is lost.

- Lever/Pedal: Manual operation by an operator.

- Pilot (Triangle): Hydraulic or pneumatic pressure shifts the valve.

Understanding Center Positions (4/3 Valves)

For 3-position valves, the center box represents the "neutral" state. This is critical for safety and system design.

- Closed Center: All ports blocked. Cylinder is locked in place; pump flow is blocked (requires relief valve).

- Open Center: All ports connected to Tank. Cylinder floats; pump unloads to tank (saves energy).

- Tandem Center: Ports A & B blocked; P connected to T. Cylinder locked; pump unloads to tank.

Understanding these symbols transforms a schematic from a confusing drawing into a clear roadmap of system logic. Start with the boxes, follow the arrows, and check the port labels—it's the universal language of fluid power.