When you open a hydraulic circuit schematic and see those curved lines with arrows pointing through them, you're looking at flow control valves. These symbols might seem simple, but they tell you exactly how a machine controls speed, manages energy, and protects expensive components. A hydraulic flow control valve diagram is not just a drawing. It's a language that reveals whether a drilling machine will chatter during breakthrough, whether an excavator arm will drift under load, or whether a system will waste energy heating up the oil tank.

The Physics of Flow Control

Flow control valves work by changing the size of an opening that oil flows through, which engineers call the throttling orifice. This restriction changes how much fluid can pass per minute, which directly controls how fast a cylinder rod moves or how quickly a hydraulic motor spins. The relationship follows a specific physical law: flow rate Q equals the discharge coefficient times the orifice area times the square root of pressure difference divided by fluid density:

This square root relationship means that doubling the pressure difference only increases flow by about 40 percent, not 100 percent.

The diagram symbols for these valves follow the ISO 1219-1 standard, which industrial engineers worldwide use to document hydraulic systems. Learning to read these diagrams means understanding what each line, arrow, and geometric shape represents in physical hardware sitting inside a valve body.

Decoding ISO 1219-1 Symbol Components

A basic throttle valve appears on hydraulic flow control valve diagrams as two curved lines facing each other, creating a narrow passage for fluid. These opposing arcs represent flow restriction. When you see a diagonal arrow passing through this symbol, it means the valve is adjustable. Someone can turn a knob or adjust a screw to change how much the valve opens. If there's no arrow, you're looking at a fixed orifice that cannot be adjusted after installation.

The direction matters critically in these diagrams. A check valve symbol looks like a ball sitting in a V-shaped seat. When fluid flows against the ball, it seals tight. When fluid flows the other way, it pushes the ball off its seat and flows freely. Many flow control applications only need speed control in one direction. For example, a machining table needs slow feed going into the cut but should return quickly. This is where the single-direction throttle valve comes in.

On a hydraulic flow control valve diagram, a single-direction throttle combines the throttle symbol with a parallel check valve symbol. The two components sit side by side, often enclosed in a dashed box showing they're built into one physical valve body. Oil flowing one way gets throttled and slows down the actuator. Oil flowing the opposite direction pushes open the check valve and bypasses the throttle completely, allowing fast return motion with minimal pressure drop.

Pressure compensated flow control valves add another symbol element: a small vertical arrow on the inlet line pointing upward. This arrow tells you the valve contains an automatic pressure regulator built in series with the manual throttle. The pressure compensator maintains a constant pressure drop across the throttle orifice regardless of load changes. Without this feature, when a cylinder pushes against a heavier load, the increased back pressure reduces the pressure difference across the throttle, which automatically slows down the motion even though the throttle setting didn't change. The compensation mechanism fixes this problem by sensing both upstream and downstream pressures and automatically adjusting an internal valve element to keep the pressure drop at exactly 0.5 to 1.0 MPa.

Temperature compensation symbols appear less commonly but matter for precision applications. A small circle or thermometer icon near the throttle symbol indicates the valve uses a sharp-edged orifice design rather than a long, narrow passage. Sharp edges create turbulent flow where the discharge coefficient stays relatively stable despite viscosity changes. As hydraulic oil heats up during operation, its viscosity drops exponentially. In long, thin passages operating under laminar flow conditions, this viscosity change significantly affects flow rate according to the Hagen-Poiseuille law. A sharp-edged orifice minimizes this temperature sensitivity, which engineers call temperature compensation.

Main Categories of Flow Control Valves

Hydraulic flow control valve diagrams show three fundamental valve families, each with distinct symbol characteristics and operating principles.

The Simple Throttle Valve

The simple throttle valve represents the most basic design. Its diagram symbol shows only the adjustable restriction without any additional components. Physically, this valve typically uses a needle-shaped spool with a very small taper angle sitting against a sharp-edged seat. Rotating an adjustment handle moves the needle axially along a fine thread, creating precise changes in the annular flow area. These valves cost less and take up minimal space, but their flow rate changes whenever system pressure fluctuates or oil temperature varies. They work acceptably for applications where load stays constant, like a grinding wheel drive or a conveyor belt, but they cannot maintain stable speed under varying load conditions.

Pressure Compensated Valves

Pressure compensated valves, also called flow control valves with compensation or simply flow regulators, appear on diagrams with that characteristic pressure-sensing arrow symbol. Inside the valve body sits two restrictions in series: the manually adjustable throttle and an automatic pressure regulator. The regulator consists of a spring-loaded spool that senses the pressure both before and after the manual throttle. When load increases and the downstream pressure rises, the differential pressure across the throttle tries to decrease. The compensator spool immediately responds by opening further, reducing its own restriction, which forces the upstream pressure to rise just enough to restore the original pressure drop across the manual throttle. This happens continuously and automatically while the system operates.

The force balance on the compensator spool creates this self-adjusting behavior. The spring force pushes the spool toward the closed position. The downstream pressure (load pressure) also pushes it toward closed. The upstream pressure pushes it toward open. At equilibrium, upstream pressure equals downstream pressure plus the spring force divided by the spool's effective area. By careful spring selection during valve design, manufacturers set the compensated pressure drop to a specific value, typically 0.5 MPa for small valves up to 1.0 MPa for large industrial valves. Because this pressure drop stays constant regardless of load, and because the throttle area is manually set and fixed, the flow rate becomes load-independent. An excavator boom will extend at the same speed whether the bucket is empty or carrying two tons of dirt.

Priority Valves

Priority valves show up in hydraulic flow control valve diagrams as a rectangular box containing a spring-biased spool with three ports labeled P (pump), CF (constant flow or priority), and EF (excess flow or bypass). These valves ensure critical functions receive their required flow first before feeding less critical circuits. The classic application is steering systems on wheel loaders and agricultural tractors. The steering circuit connects to CF, while work functions like bucket tilt connect to EF. A pressure signal line from the steering unit feeds back to one end of the priority valve spool, pushing against the spring. When the operator turns the steering wheel quickly, this signal pressure rises, shoving the spool over to route maximum flow to CF while choking off EF. When steering demand drops, the spool returns under spring force, allowing flow to the work functions. This prevents the dangerous situation where an operator cannot steer because all pump flow is being consumed by a hydraulic hammer or other attachment.

Flow Divider Valves

Flow divider valves, shown on diagrams as a box with two outputs and interconnected throttle symbols inside, force equal (or proportionally split) flow to two or more actuators regardless of their individual load differences. Synchronizing two cylinders pushing unequal loads normally fails because the lower-resistance cylinder runs ahead. The divider contains two precisely matched throttling elements with pressure feedback paths connecting them. If one side sees higher load, its increased pressure communicates through an internal passage to the other side's throttle, which then automatically restricts more to equalize the flow split. Gear-type dividers use two hydraulic motors rigidly coupled on a common shaft, mechanically forcing equal displacement.

Circuit Configuration Strategies

Where you place a flow control valve in a hydraulic circuit fundamentally changes system behavior, efficiency, and safety characteristics. The three classical arrangements are meter-in, meter-out, and bleed-off circuits. Understanding their diagram representations helps engineers diagnose speed problems and select appropriate solutions.

Meter-In Throttling Configuration

In meter-in circuits, the hydraulic flow control valve diagram shows the flow control element positioned between the pump and the actuator inlet. This placement restricts oil entering the cylinder, controlling extension speed by limiting available fluid. The pump continues delivering its full displacement, but excess flow above what passes through the throttle goes over the relief valve back to the tank.

The pressure characteristics become clear when analyzing the forces. The cylinder's inlet pressure equals load force divided by piston area ($$P_1 = F/A$$). The pump side pressure gets clamped at the relief valve setting, typically 15 to 35 MPa depending on application. This creates a large, constant pressure drop across the valve, which generates heat equal to pressure times flow ($$P \\times Q$$). The system runs hot, and the pump works hard against relief pressure even when doing light work.

Meter-in throttling works smoothly for resistive loads where the external force opposes cylinder motion. A milling machine table feeding into a workpiece or a grinding wheel advancing against a casting both represent resistive loads. The motion stays controlled and predictable. However, meter-in creates a dangerous condition with overrunning loads, also called negative loads or runaway loads. Consider a vertical cylinder lowering a heavy weight. Gravity pulls the piston rod downward faster than the throttled inlet flow can fill the extending side. This creates vacuum in the cylinder chamber, causing cavitation damage, erratic motion, and potential load crash. For this reason, engineers never use meter-in throttling for boom-down, forklift-lower, or any application where the load aids cylinder motion. Hydraulic flow control valve diagrams for these applications must show meter-out or balanced circuit configurations instead.

Meter-Out Throttling Configuration

Meter-out places the flow control valve on the actuator's exhaust port. The diagram shows the valve between the cylinder and tank, restricting oil flowing out. The inlet side connects fairly directly to the pump, allowing free filling of the extending chamber. The cylinder moves only as fast as the throttle permits oil to escape from the retracting chamber.

This arrangement creates back pressure in the exhaust side, which provides stiffness and control even with overrunning loads. When gravity pulls a suspended load downward, the throttled exhaust port prevents runaway by holding back pressure. The cylinder effectively brakes itself hydraulically. This makes meter-out the standard choice for vertical drilling spindles, crane boom lowering, and any application needing control of negative loads.

Critical Engineering Consideration: Pressure Intensification

Because the cap end (full area) connects to pump pressure while the rod end (annular area) gets throttled, a force balance shows the rod-side pressure can reach very high values. The relationship follows:

With a 2:1 area ratio (common with standard rod sizes), the rod-side pressure reaches roughly double the pump pressure plus the load pressure component. If the pump runs at 20 MPa and there's a resistive load adding another 5 MPa equivalent, the rod-side pressure hits 45 MPa. This can burst hoses, blow seals, or crack fittings not rated for such pressure.

Meter-out excels at motion smoothness and load holding. The high back pressure eliminates any looseness in the system and prevents stick-slip oscillations that cause jerky motion at low speeds. Machining operations requiring fine surface finish and crane operators needing smooth load placement both benefit from meter-out control. The tradeoff is lower efficiency and higher heat generation compared to bleed-off systems.

Bleed-Off (Bypass) Throttling

Bleed-off circuits show the flow control valve in a branch line parallel to the actuator, creating a shortcut path directly to tank. The diagram depicts pump flow splitting at a tee, with one path going through the valve to tank and the other path feeding the cylinder. This is subtraction control - the valve diverts away unwanted flow rather than restricting actuator supply.

The pump flow splits into cylinder flow plus bleed-off flow ($$Q_{pump} = Q_{cylinder} + Q_{bleedoff}$$). Opening the bleed valve drains more flow to tank, slowing the cylinder. Closing it routes more flow to the actuator, speeding up motion. The crucial difference from meter-in and meter-out is that the pump never needs to develop full relief pressure unless the load requires it. If the cylinder pushes against only 5 MPa of load pressure, the pump only builds 5 MPa (plus a small margin for line losses). Excess flow bleeds off at this low working pressure, not at 20 or 30 MPa relief setting. The power waste equals $$P_{load} \\times Q_{excess}$$, which is substantially less than $$(P_{relief} \\times Q_{excess})$$ in meter-in/out systems.

This efficiency advantage makes bleed-off attractive for energy-conscious applications like agricultural equipment, material handling conveyors, and mobile equipment where fuel consumption matters. The system runs cooler and wastes less energy as heat. However, bleed-off provides poor speed stability because the pump flow changes with pressure (volumetric efficiency drops as pressure rises), and the bleed valve flow also varies with the changing pressure across it. When load fluctuates, speed fluctuates. This limits bleed-off to applications where absolute speed precision is not critical, such as mixer agitators or intermittent shuttle conveyors. Like meter-in, bleed-off cannot safely handle overrunning loads because it doesn't create back pressure to resist load-induced motion. The actuator would accelerate under gravity or inertia regardless of the bleed valve setting.

| Characteristic | Meter-In | Meter-Out | Bleed-Off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valve Position | Between pump and actuator inlet | Between actuator outlet and tank | Parallel to actuator, to tank |

| Load Type Suitable | Resistive only | Resistive and overrunning | Resistive only |

| System Pressure | Constant at relief setting | Constant at relief setting | Varies with load |

| Motion Smoothness | Good | Excellent (high stiffness) | Fair to poor |

| Energy Efficiency | Low | Low | High |

| Cavitation Risk | High with negative loads | Low | High with negative loads |

Advanced Diagram Features for Complex Systems

Real-world hydraulic flow control valve diagrams often combine multiple valve types and add sensing elements to handle sophisticated control requirements.

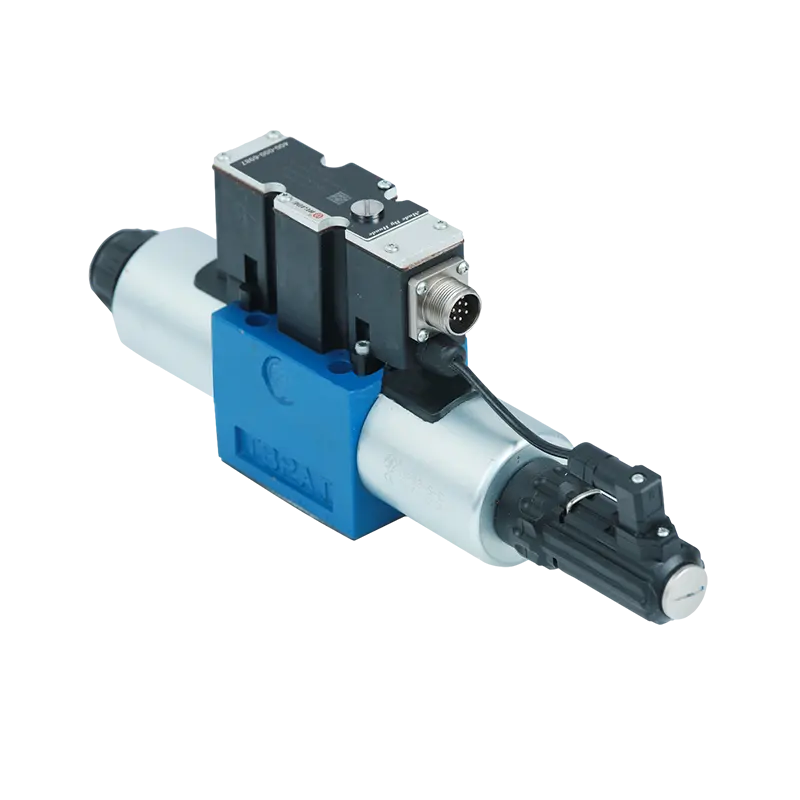

Proportional flow control valves appear on diagrams with an additional box symbol representing the proportional solenoid. This electrical actuator replaces the manual adjustment knob. Current flowing through the solenoid coil creates a magnetic force proportional to amperage, pushing the valve spool to a corresponding position. A 200 mA signal might produce 20 percent valve opening, while 1000 mA gives full flow. Modern proportional valves include linear variable differential transformers (LVDT sensors) that measure actual spool position and feed back to the amplifier for closed-loop control. This allows computer-controlled acceleration ramps, deceleration profiles, and multi-point velocity programs impossible with manual valves.

``` [Image of proportional flow control valve diagram] ```Hydraulic flow control valve diagrams for injection molding machines show proportional valves controlling the injection screw motion through complex velocity curves. The screw starts slowly to avoid jetting, then speeds up for rapid cavity filling, then slows again approaching full to prevent overpacking and flash. The control program might have eight different velocity setpoints across the injection stroke, with smooth transitions between them. The diagram includes position sensors (drawn as small boxes on the cylinder) that tell the controller where the screw is, allowing precise velocity synchronization with position.

Load-sensing priority valves represent an evolution of basic priority valves. The diagram shows an additional signal line (typically drawn as a thin dashed line) running from the steering orbital valve back to the priority valve. This line carries a pressure signal proportional to steering demand. When the operator turns the wheel slowly with no load, the signal pressure is low, maybe 2 to 3 MPa. The priority valve's compensator only opens the CF port partially, sending just enough flow for that gentle steering input while allowing most flow to EF for working attachments. When the operator whips the wheel around at full speed or encounters high resistance in the steering cylinders, the signal pressure jumps to 15 MPa or more. This pressure acts on the priority valve spool against its spring, forcing the valve fully open to CF and nearly closed to EF, ensuring all available pump flow goes to steering. The result is steering that always feels responsive without wasting pump capacity when steering demand is light. This dynamic load-sensing system improves fuel economy compared to older constant-flow priority systems.

Flow divider circuits for synchronized cylinders show internal feedback paths on the hydraulic flow control valve diagram as crossed dotted lines connecting the two throttling elements. One branch might show higher load pressure, causing its throttle element to open slightly. Through the pressure equalization passage, this pressure signal reaches the other branch's control piston, forcing its throttle to restrict proportionally. The two sides continuously adjust to maintain the designed flow ratio, commonly 50-50 for equal cylinders or 60-40 or other ratios for unequal loads. The diagram clearly distinguishes between motor-type dividers (shown with two gear symbols on a common shaft) and spool-type dividers (shown with interconnected throttle elements). Motor-type dividers provide extremely accurate division but cost more and occupy more space. Spool-type dividers suffice for applications like dump truck tailgate synchronization where precision within 5 percent is adequate.

Industrial Application Case Studies

Looking at complete system diagrams reveals how engineers combine flow control valves to solve real operational challenges.

Excavator swing circuits illustrate sophisticated use of meter-out throttling. The hydraulic flow control valve diagram for a 30-ton excavator's slew drive shows the hydraulic motor's drain ports feeding through meter-out throttle-check valves before reaching tank. When the operator starts rotation, these valves restrict outflow, building back pressure that smoothly accelerates the 8-ton upper structure without shock. As the swing approaches target position, the operator returns the joystick toward neutral, and the main control valve starts routing flow back to tank. But the rotating mass has tremendous inertia and wants to keep spinning. The motor now acts as a pump driven by inertia, pushing oil backward through the circuit. The meter-out restriction prevents this free reverse flow, creating braking resistance. Without this feature, the machine would overshoot its target by meters and then oscillate as the operator fought to stop the swinging mass. The diagram also shows cross-connected relief valves between the motor ports. These safety valves limit peak deceleration pressure to around 35 MPa. When emergency braking occurs (operator joystick slammed to neutral), the inertia spike would otherwise create pressure exceeding 50 MPa, which would damage motor seals and bearings.

``` [Image of excavator hydraulic swing circuit diagram] ```Injection molding machine diagrams demonstrate the transition from flow control to pressure control during the molding cycle. The main injection cylinder operates through several phases visible on the hydraulic flow control valve diagram. During mold filling, a large proportional flow valve controls velocity as the screw rams molten plastic into the cavity. The diagram shows flow moving through the valve to the cylinder's cap end while the rod end drains freely to tank. Filling might take 1 to 3 seconds depending on part size. As the mold reaches 95 percent full, a pressure transducer (shown as a small diamond symbol) on the cap-end line detects rising pressure. The controller switches modes. The proportional flow valve reduces to a small opening (shown by decreased current signal) while a proportional pressure valve (different symbol, shown with a pressure spring icon) takes over, holding pack pressure at perhaps 10 to 15 MPa for 5 to 20 seconds while the plastic cools. This pressure prevents sink marks as the polymer shrinks. The mode transition requires both valves to act simultaneously in coordinated fashion, which the diagram captures with control lines (electrical, shown as dashed lines) running from both valves to a central controller box.

Regenerative circuits for fast approach motion appear frequently in press and molding machine diagrams. To speed up a 500-ton press approaching the workpiece before applying forming force, engineers connect the cylinder's rod-end port to its cap-end port through a pilot-operated check valve. This creates a closed loop where oil leaving the rod side (area A₁) flows directly into the cap side (area A₂ = A₁ - A_rod) instead of going to tank. Because A₂ is smaller than A₁, the rod-side discharge exceeds cap-side demand. The pump supplies the deficit (A_rod area flow), but at the speed determined by pump flow divided by just the rod area, which is typically 3 to 5 times faster than normal extension speed. When the ram contacts the workpiece, load pressure rises, which acts on the pilot-operated check valve shown in the diagram. The rising pressure closes the regeneration path, and the circuit transitions to normal extension with full force capability. The hydraulic flow control valve diagram must clearly show this regeneration loop with proper valve orientation, as installing the check valve backward would lock up the entire system.

Diagnostic Troubleshooting Using Diagrams

When a hydraulic system develops speed control problems, the circuit diagram provides a troubleshooting roadmap by revealing pressure relationships and failure points.

Flow drift over time usually indicates temperature-related effects or pressure compensation failure. If a system slows down after 20 minutes of operation, the first diagnostic step is confirming whether the flow control valve has the temperature compensation feature (sharp-edged orifice symbol on the diagram). Standard needle valves without compensation will show flow increases of 15 to 25 percent as the system warms from 30°C to 60°C because the oil viscosity drops exponentially with temperature. Under laminar flow conditions in long throttling passages, flow rate is inversely proportional to viscosity according to Hagen-Poiseuille flow principles. If the diagram shows a temperature-compensated valve (indicated by the dot-and-line symbol or sharp-edge notation), but drift still occurs, the problem likely lies in contamination. Varnish deposits from oxidized oil coat the compensator spool, creating friction that prevents the spool from tracking pressure changes properly. The compensator gets "stuck" in one position, turning an expensive pressure-compensated valve into a basic throttle valve with load-dependent flow.

Checking the actual pressure drop across the suspect valve confirms this diagnosis. Install pressure gauges at the inlet and outlet ports shown on the hydraulic flow control valve diagram. Measure differential pressure under no-load and full-load conditions. A functional compensator maintains constant ΔP (typically 0.5 to 1.0 MPa) regardless of load. If ΔP drops significantly under load, the compensator has failed. The remedy is disassembly and cleaning, or replacement if wear limits have been exceeded. The ISO 4406 cleanliness code for the oil should be 19/17/14 or better for precision valves, meaning no more than 2500 particles larger than 4 microns per 100mL of fluid.

Reverse direction speed problems with single-direction throttle valves point directly to check valve malfunctions. The diagram shows oil flowing backward through the valve should easily push open the check ball and bypass the throttle. If reverse motion is slow, the check ball is stuck closed by contamination, or the check spring has broken and jammed the ball into an intermediate position that partially blocks flow. An infrared temperature gun scanning the valve body often reveals this failure - the area around the stuck check valve runs extremely hot (possibly 80 to 90°C) from the high pressure drop as oil is forced through the tiny throttling gap instead of the check valve's large bypass area. The temperature rise equals pressure drop times flow divided by the specific heat capacity and mass flow rate of the oil, and it's easily measured with non-contact instruments.

Cylinder creeping (slow drift under load) when the directional valve sits in neutral position indicates internal leakage past the flow control valve's spool or seat. This doesn't show on the diagram directly, but understanding the circuit helps diagnosis. If the diagram shows meter-out throttling, the cylinder is locked by trapped oil when the directional valve closes. The high trapped pressure on the rod side creates a pressure difference across the flow control valve even though both its ports connect to blocked chambers. Any wear on the valve spool or seat allows micro-leakage from high pressure to low pressure, and the cylinder slowly drifts. The only solutions are tighter-sealing valves (zero-leak poppet designs rather than spool types), adding a separate pilot-operated check valve (counterbalance valve) to positively lock the load, or accepting the small amount of drift if it doesn't affect operation.

Speed variations synchronized with system pressure changes signal the need for pressure compensation where none exists. If the hydraulic flow control valve diagram shows a basic throttle symbol without the compensation arrow, the valve's flow rate will track the square root of pressure difference. A circuit diagram review showing the system's relief valve setting, pump flow curve, and actuator load profile can predict the magnitude of speed variation. With a 10 MPa relief pressure and 5 MPa load pressure, the available ΔP across a meter-in throttle is 5 MPa. If load pressure rises to 7 MPa during heavy cutting, available ΔP drops to 3 MPa, and flow decreases to $$\\sqrt{3/5} = 0.77$$ or 77 percent of the original speed - a very noticeable 23 percent slowdown. The engineer sees this coming by analyzing the diagram's pressure zones and recommends upgrading to a pressure-compensated flow control valve (with the compensation arrow symbol).

| Symptom | Diagram Clues | Physical Cause | Test Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed decreases as oil warms up | Standard throttle symbol without temperature compensation marking | Viscosity decrease in laminar flow passage | Compare speed at 30°C vs 60°C oil temperature |

| Speed varies with load despite compensated valve | Compensation arrow present but ΔP measurement drops under load | Compensator spool stuck due to varnish/contamination | Measure pressure before and after throttle at no-load and full-load |

| Slow reverse speed through single-direction throttle | Check valve symbol parallel to throttle restriction | Check ball stuck closed or spring broken | IR temperature scan shows hot spot at check valve location |

| Cylinder drifts slowly in neutral position | Meter-out configuration with closed directional valve | Internal leakage past flow control spool/seat under high trapped pressure | Measure drift rate, check for external leaks first |

Reading Diagrams for System Design Decisions

Engineers use hydraulic flow control valve diagrams not just for troubleshooting but as predictive tools during system design to avoid problems before they occur.

When selecting circuit topology, the diagram helps visualize energy flow and loss mechanisms. Drawing the complete circuit with all restrictions shown reveals where throttling losses occur. In a meter-in system, the energy waste equals pump pressure times excess flow going over the relief valve. For a 100 liter/minute pump running at 20 MPa relief pressure with only 40 LPM going to the actuator through the throttle, the heat generation is $$20 \\text{ MPa} \\times 60 \\text{ LPM} = 20 \\text{ kW}$$ of pure thermal waste. This needs a large oil cooler, and the fluid reaches temperatures around 65°C even with cooling. The same application using bleed-off topology might run at only 8 MPa working pressure (determined by the load), making the waste $$8 \\text{ MPa} \\times 60 \\text{ LPM} = 8 \\text{ kW}$$, which is less than half the thermal load. The system can use a smaller cooler, the oil stays at 45°C, pump life extends by years, and electrical power consumption drops proportionally.

Pressure intensification calculations come directly from the diagram's geometry. When a cylinder shows 100mm bore and 50mm rod diameters, the cap-end area is 7854 mm² while the rod-end area is only 5890 mm² (annular area = full area minus rod area). The area ratio of 1.33 means that meter-out throttling will intensify pressure by at least 33 percent. If the pump supplies 15 MPa to the cap end, the rod-end pressure under no external load becomes at least 20 MPa due to geometry alone. Add a resistive load pushing back with 3 MPa, and rod-end pressure reaches 23 MPa. Every hose, fitting, and seal on that rod-end circuit needs a pressure rating above 25 MPa (with safety margin), or failures will occur. Engineers mark these calculations directly on the diagram with pressure annotations showing expected maximums at each location.

The diagram also guides flow valve sizing. Flow coefficients Cv or Kv appear in valve catalogs, indicating the flow rate at 1 bar pressure drop. If the system requires 60 LPM through a pressure-compensated valve that maintains 0.5 MPa (5 bar) ΔP, then working backward, the valve needs $$Cv = Q / \\sqrt{\\Delta P} = 60 / \\sqrt{5} = 27$$ gallons per minute at 1 bar. This determines which model from the manufacturer's range fits the application. Oversizing wastes money and creates slow control response; undersizing causes excessive pressure drop, heating, and erosion.

Understanding how multiple flow control valves interact prevents design mistakes. A common error is placing two throttles in series without recognizing they form a voltage divider equivalent. If valve A has opening area A₁ and valve B has opening area A₂, both in series, the total flow is determined by the smaller opening and the sum of pressure drops. The engineer cannot independently control speed with both valves - adjusting valve A changes the pressure distribution and affects valve B's flow even if B's setting doesn't change. The hydraulic flow control valve diagram must show these series restrictions, and the design should eliminate redundant restrictions or intentionally use them for precise control of the pressure drop ratio.

Conclusion

Hydraulic flow control valve diagrams using ISO 1219-1 symbols provide engineers with a complete understanding of system speed control, energy efficiency, and failure modes before building hardware. The curved restriction symbols tell whether a valve operates as a basic throttle, pressure-compensated regulator, or priority divider. The arrow indicators reveal adjustability and compensation features. The circuit placement - meter-in, meter-out, or bleed-off - determines load capability and efficiency. Reading these diagrams requires understanding both the graphic standards and the fluid mechanics principles behind each symbol. A diagonal arrow means human adjustment. A vertical arrow means pressure compensation. A parallel check valve means single-direction control with free reverse flow.

Engineers select circuit topology by analyzing load direction, required stiffness, acceptable efficiency, and pressure ratings. They diagnose failures by comparing diagram predictions against measured pressures and temperatures. They size components using flow equations and pressure calculations derived from circuit geometry. The diagram serves as a common language between designers, technicians, and troubleshooters, allowing someone in Chicago to diagnose a machine operating in Singapore by reviewing the schematic and asking for specific pressure measurements at marked test points.

Mastering hydraulic flow control valve diagrams means recognizing that every line and symbol represents physical hardware and measurable energy transformations. The squeeze between two curved lines represents molecule collisions in a turbulent jet, temperature rises from friction, and precise speed control that makes modern machinery possible. Whether the application is an excavator boom lowering safely under gravity, an injection mold filling with eight-segment velocity profiling, or a simple grinding table feeding at constant speed, the diagram reveals exactly how flow control accomplishes the task and where problems might emerge.