If you have ever adjusted a kitchen faucet to get just the right water flow, you have used the same principle that industrial throttle valves employ every day in systems handling everything from hydraulic oil to natural gas. A throttle valve is a mechanical device that controls fluid flow rate and system pressure by introducing a variable restriction in the flow path. Unlike simple on-off isolation valves, throttle valves are designed to operate continuously at partial openings, converting fluid pressure energy into controlled resistance.

The technical definition becomes clearer when we look at what happens inside the valve body. As fluid approaches the throttle valve, it encounters a movable element—typically a disc, plug, or needle—that partially blocks the flow passage. This restriction forces the fluid to accelerate through the reduced cross-sectional area, following the continuity equation (Q = A × v, where Q is flow rate, A is area, and v is velocity). According to Bernoulli's principle, this velocity increase comes at the cost of static pressure. The fluid's pressure energy converts to kinetic energy at the restriction point, known as the vena contracta. After passing this narrow throat, the high-velocity jet enters the larger downstream passage where turbulence, friction, and flow separation prevent the pressure from fully recovering. This irreversible pressure drop is the fundamental mechanism that gives throttle valves their control capability.

What distinguishes throttle valves from other flow control devices is their ability to maintain stable operation under varying pressure differentials while providing predictable flow characteristics. Engineers specify throttle valves when they need precise flow modulation rather than simple shutoff, making them critical components in applications ranging from automotive engine air intake control to deepwater oil well production management.

The Physics Behind Throttle Valve Operation

Understanding why throttle valves work requires examining the energy transformations that occur during the throttling process. The starting point is the principle of energy conservation as expressed through Bernoulli's equation for steady incompressible flow:

$$P_1 + \\frac{1}{2}\\rho v_1^2 + \\rho g h_1 = P_2 + \\frac{1}{2}\\rho v_2^2 + \\rho g h_2$$

In an ideal reversible process, the sum of pressure energy, kinetic energy, and potential energy remains constant. However, real-world throttling is inherently irreversible. When fluid exits the vena contracta and enters the downstream expansion zone, the organized kinetic energy of the high-velocity jet degrades into random turbulent motion, eddy currents, and molecular friction. This chaotic energy dissipation manifests as heat and acoustic noise rather than recovered pressure. This permanent pressure loss is not a design flaw but the intended mechanism that allows throttle valves to regulate flow.

For compressible fluids like gases, throttling introduces additional thermodynamic complexity through the Joule-Thomson effect. In an adiabatic throttling process where no heat exchange occurs with surroundings, the fluid undergoes an isenthalpic expansion. Most industrial gases exhibit positive Joule-Thomson coefficients at ambient temperatures, meaning they cool down during throttling. This temperature drop is the operational basis for refrigeration expansion valves, which throttle high-pressure liquid refrigerant into a cold low-pressure mixture. However, hydrogen, helium, and neon display negative coefficients at room temperature, meaning they heat up when throttled—a critical safety consideration in hydrogen fuel systems where localized heating could trigger ignition.

The quantification of throttle valve capacity uses the flow coefficient, expressed as Cv in Imperial units or Kv in metric units. The Cv value represents the volumetric flow rate of 60°F water in gallons per minute that produces a 1 psi pressure drop across the valve. For liquid applications, the relationship follows:

$$C_v = Q \\sqrt{\\frac{SG}{\\Delta P}}$$

where Q is flow rate, SG is specific gravity, and ΔP is pressure differential.

This equation reveals the nonlinear nature of throttle valve behavior: doubling the flow through a fixed opening requires quadrupling the pressure drop. This characteristic demands careful valve sizing because an oversized valve operating at 5-10% opening produces unstable control with excessive sensitivity, while an undersized valve risks reaching choked flow conditions where velocity reaches sonic limits and further pressure reduction cannot increase flow rate.

Core Applications Across Industries

Throttle valves serve distinct functions across industrial sectors, each exploiting the fundamental pressure reduction principle in application-specific ways.

Automotive Engine Management: Modern gasoline engines use electronic throttle control (ETC) systems where a butterfly valve in the intake manifold regulates airflow into the combustion chambers. Unlike legacy cable-actuated throttles directly linked to the accelerator pedal, ETC systems employ dual-redundant accelerator pedal position sensors (APP) feeding signals to the engine control unit (ECU). The ECU commands a DC motor to position the throttle plate based on integrated logic that incorporates traction control, cruise control, and emissions strategies. The system includes dual-path throttle position sensors (TPS) with voltage outputs that move in opposite directions—if both signals don't correlate within tolerance, the ECU enters limp mode and restricts engine speed to prevent runaway conditions. One peculiar phenomenon in ETC systems involves carbon accumulation from positive crankcase ventilation (PCV) gases forming deposits around the throttle bore edges, progressively restricting idle airflow. The ECU compensates by adaptively increasing idle opening from perhaps 3% to 5% over time. When technicians clean the throttle body and remove these deposits, the remembered 5% opening now allows excessive airflow, causing elevated idle speed until a throttle relearn procedure forces the ECU to rediscover the physical closed position and reestablish baseline airflow characteristics.

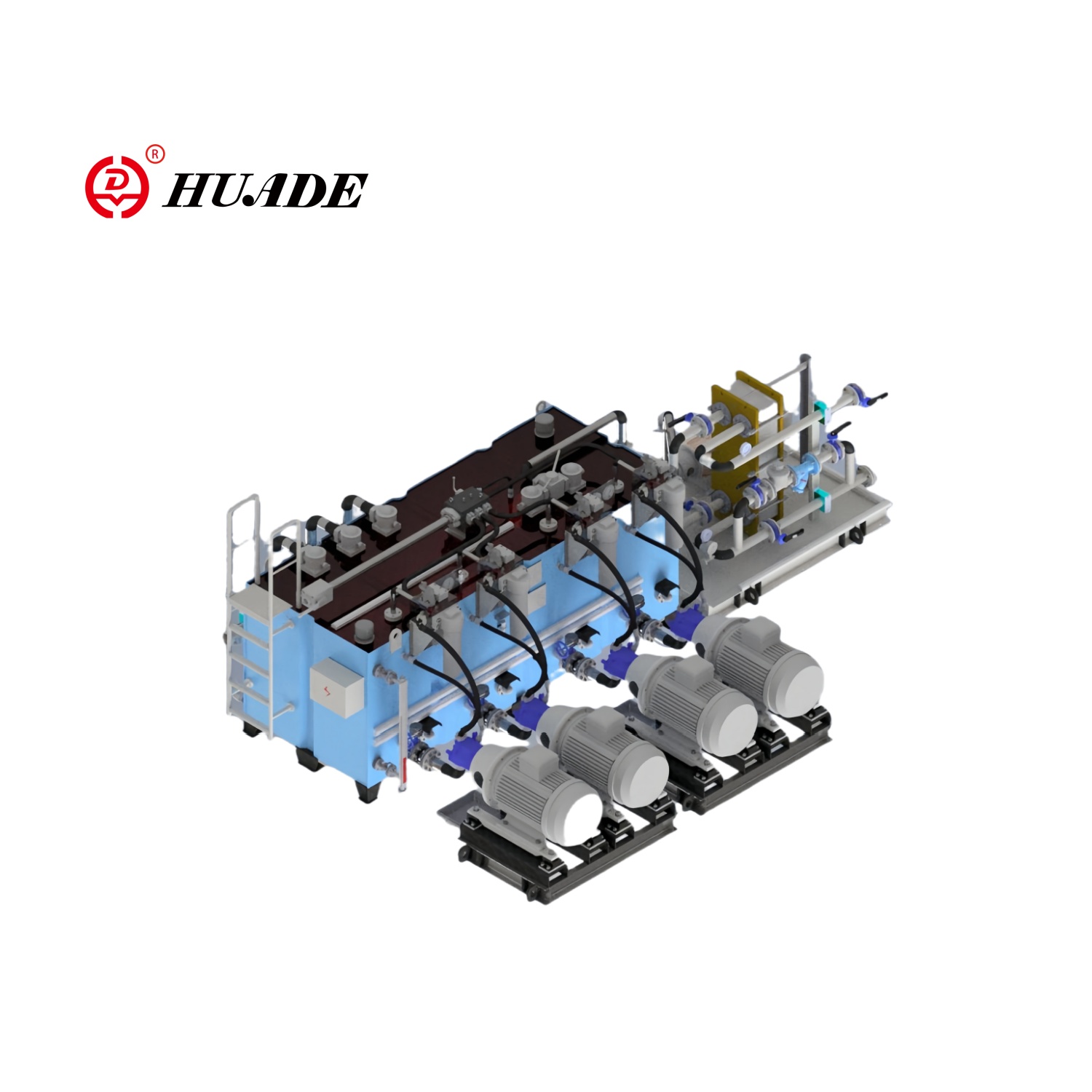

Hydraulic Power Systems: In mobile and industrial hydraulic circuits, throttle valves—often called flow control valves in this context—govern actuator speed independently of pump output. The valve placement in the circuit determines load handling characteristics. Meter-in throttling restricts flow entering the cylinder, suitable for resistive loads where the load opposes motion (like lifting). However, meter-in configurations become dangerous with overrunning loads (lowering a suspended weight) because gravity can pull the piston faster than supply flow enters, creating vacuum conditions and loss of control. Meter-out throttling addresses this by restricting return flow, building back-pressure in the rod-side chamber that acts as a hydraulic brake against the overrunning load. This configuration provides superior motion stability and prevents load drop, though engineers must account for pressure intensification in single-rod cylinders where the area ratio between cap-end and rod-end chambers can multiply pressures beyond relief valve settings, potentially causing seal failure if not properly calculated using the pressure ratio formula: P_rod = (P_cap × A_cap + F_load) / A_rod.

Refrigeration and HVAC: Expansion valves in vapor-compression refrigeration cycles perform the critical throttling function that enables cooling. Thermostatic expansion valves (TXV) operate through elegant mechanical feedback using a three-force balance: the sensing bulb pressure opening the valve (responding to evaporator outlet temperature), opposed by evaporator pressure and spring preload both acting to close the valve. This purely mechanical system maintains optimal superheat—the temperature margin above saturation that ensures only vapor enters the compressor. Modern variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems increasingly employ electronic expansion valves (EEV) driven by stepper motors receiving pulse commands from microcontrollers. These provide micrometer-level needle positioning with millisecond response times, eliminating the hunting oscillations that plague TXVs at low loads and enabling sophisticated feedforward control strategies.

Upstream Oil and Gas: Wellhead choke valves on Christmas trees control production rates from oil and gas wells operating at formation pressures reaching 10,000-15,000 psi. These face arguably the harshest service conditions in valve engineering: multiphase flow (crude oil, natural gas, formation water) containing abrasive sand particles at velocities that turn the sand into a cutting jet. Choke valve trim uses tungsten carbide or specialized ceramics, with designs that direct high-velocity flow toward the pipe centerline to avoid body erosion. The distinction between API 6A (wellhead equipment) and API 6D (pipeline valves) standards is critical—using an API 6D ball valve for wellhead throttling will result in rapid erosion perforation since pipeline valves are designed for isolation duty in horizontal installations with full-bore passages for pig passage, not the vertical high-pressure differential service that wellhead equipment must withstand.

Common Types of Throttle Valves and Their Selection

Different throttle valve designs offer distinct flow characteristics, pressure drop profiles, and suitability for specific service conditions. Understanding these differences is essential for proper application selection.

| Valve Type | Throttling Precision | Pressure Drop | Cavitation Resistance | Typical Applications | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Globe Valve | Excellent (linear stem travel) | High | High (with anti-cavitation trim) | Steam control, boiler feedwater, chemical process | High resistance even when fully open |

| Needle Valve | Extremely precise (micro-flow) | Very high | Moderate | Instrumentation sampling, laboratory flow control | Limited to small sizes (<2 inches), clean fluids only |

| V-Port Ball Valve | Good (characterized flow) | Moderate | Moderate | Slurries, fibrous media (pulp and paper) | Less precise than globe valves |

| Butterfly Valve | Fair (effective 30-70% opening only) | Low | Low (fast pressure recovery) | Large diameter HVAC, cooling water, low-pressure gas | Limited throttling range, poor tight shutoff |

| Gate Valve | PROHIBITED | Very low (full open) | Poor (rapid seat damage) | Isolation only (not throttling) | Throttling causes vibration and wire-drawing erosion |

Globe valves represent the industry standard for precision throttling. Their internal flow path forces fluid through an S-shaped or Z-shaped passage with a right-angle turn at the seat, creating substantial pressure loss. The valve plug moves perpendicular to the seat, establishing a nearly linear relationship between stem position and flow area. This geometry enables accurate flow modulation with predictable response. Modern control globe valves use cage-guided trim where the plug slides within a cylindrical cage with machined openings. The cage serves dual purposes: it provides full-stroke mechanical guidance preventing lateral vibration from unbalanced forces, and the opening geometry determines flow characteristics (linear, equal percentage, quick opening) without changing the valve body or actuator. Simply swapping cages with different port patterns allows characteristic modification.

Needle valves extend globe valve principles to extremely small flow rates using a long tapered needle as the closure element. The fine taper requires multiple stem rotations to produce small flow area changes, creating a mechanical reduction ratio that enables microflow adjustment. These valves commonly handle instrumentation applications and hydraulic damping circuits where flow rates measure in milliliters per minute. However, their small passages limit use to clean fluids and sizes typically remain under 2 inches.

Critical Note: The prohibition against using gate valves for throttling deserves emphasis. Gate valves employ a sliding disc (gate) that lifts perpendicular to flow to provide full-bore passage when open. At partial opening, the gate's bottom edge protrudes into the flow stream, creating a restriction. High-velocity fluid hammering against this edge generates severe vibration known as chattering. More destructively, the concentrated high-speed jet cutting across the sealing surfaces causes wire-drawing erosion—grooves cut into the seat and disc that permanently prevent tight shutoff. Industry standards explicitly prohibit gate valve throttling, yet this remains a common error in field installations.

V-port ball valves modify standard ball valve designs by machining a V-shaped notch into the ball. This contoured opening creates a more gradual flow increase compared to standard balls that produce rapid flow surge at small opening angles. The V-port delivers approximately equal-percentage characteristics where each increment of stem travel produces a flow change proportional to the current flow rate rather than a fixed change. The V-notch geometry also provides a shearing action beneficial for fibrous or slurry services where the sharp edge can cut through suspended solids.

How Throttle Valves Control Flow in Hydraulic Systems

Hydraulic circuit design places throttle valves strategically to achieve specific control objectives. The valve location relative to the actuator determines system response to varying loads and defines safety characteristics.

In meter-in throttling configurations, the flow control valve installs between the pump and cylinder inlet. This arrangement restricts fluid entering the actuator, directly limiting extension speed. Meter-in works acceptably with resistive loads where external forces oppose the desired motion direction—for example, a hydraulic cylinder lifting a weight against gravity. The load pressure assists in maintaining positive pressure throughout the circuit.

However, meter-in becomes hazardous when handling overrunning loads where gravity or other forces act in the same direction as desired motion. Consider a crane lowering a suspended load. If flow control is on the inlet side, gravity pulling the load downward can force the piston to move faster than pressurized fluid enters the cylinder. This creates a vacuum in the extending chamber, causing dissolved air to come out of solution, potentially vaporizing the hydraulic fluid (cavitation), and resulting in complete loss of motion control as the load free-falls. This scenario has caused industrial accidents when operators unknowingly configured circuits with meter-in for lowering operations.

Meter-out throttling solves overrunning load problems by placing the flow control valve in the cylinder's return line. Supply flow enters the cylinder unrestricted while return flow must pass through the throttle restriction. This builds back-pressure in the chamber being exhausted, creating a hydraulic braking force that opposes the overrunning load. The trapped fluid physically prevents the piston from being pulled faster than supply oil enters, maintaining positive control even with heavy suspended loads moving downward.

The safety advantage of meter-out carries a pressure intensification risk that requires calculation during design. In single-rod cylinders, the cap-end (piston-side) area exceeds the rod-end (annulus) area. When retracting under meter-out control with an assisting load, the pressure in the smaller rod-end chamber can be amplified according to the area ratio. If supply pressure is 2000 psi entering a 10 square inch cap area, and the rod area is only 2 square inches, the rod-end pressure can theoretically reach 10,000 psi when supporting a load. If the system relief valve only protects the supply side at 2500 psi, the rod-end chamber may experience pressures far exceeding safe limits, potentially rupturing seals or fracturing the cylinder tube. Proper design requires independent relief protection for the rod-end circuit or careful verification that maximum intensified pressure stays within component ratings.

Bleed-off throttling represents a third configuration where the throttle valve is installed in a parallel branch that dumps excess pump flow directly to tank. Only the flow needed by the actuator enters the working circuit. This achieves high efficiency since unused flow returns to tank at low pressure, wasting minimal energy. However, actuator speed becomes highly load-dependent because varying load pressures change the pressure drop across the bleed-off orifice, altering the flow split ratio. Bleed-off finds application only where loads remain relatively constant and precise speed control is not required.

When You Should NOT Use a Throttle Valve

Understanding throttle valve limitations prevents costly mistakes and unsafe conditions. Several applications demand alternative approaches.

The gate valve prohibition bears repeating due to persistent misuse. Gate valves are exclusively isolation devices engineered for full-open or full-closed service. Their straight-through flow path when fully open provides minimal pressure drop, making them ideal for mainline shutoff. But any attempt at partial-opening throttling subjects the gate to destructive high-velocity erosion and violent vibration. Maintenance costs from replacing prematurely worn gate valve internals far exceed the expense of installing a proper throttle valve in parallel.

Applications requiring absolute zero leakage in the closed position exceed throttle valve capabilities. Most industrial throttle valves employ metal-to-metal seats that achieve FCI Class IV leakage ratings (0.01% of capacity), adequate for process control but insufficient for environmental isolation. When regulations mandate zero emissions during shutoff—for example, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) or toxic services—the circuit requires a separate tight-shutoff isolation valve (ball or butterfly with soft seats) in series with the throttle valve. The isolation valve handles shutoff duty while the throttle valve provides flow modulation during operation.

Cavitation-prone services demand special consideration rather than standard throttle valves. When liquid system pressure drops below the fluid's vapor pressure during throttling, cavitation occurs—liquid flashes to vapor bubbles that subsequently implode when pressure recovers downstream, generating shock waves and microjets with local pressures exceeding 100,000 psi. These repetitive impacts rapidly erode metal surfaces, producing the characteristic rough, pitted texture. The cavitation index (σ) predicts susceptibility:

When σ falls below the valve's critical value, cavitation is unavoidable. Rather than using a standard single-stage throttle valve, engineers must specify multi-stage pressure reduction trim (labyrinth or drilled-hole cage designs) that divides the total pressure drop into many small steps, preventing any location from reaching vapor pressure.

Services containing solid particulates require erosion-resistant materials beyond typical throttle valve construction. Produced water from oil wells, for instance, carries sand that acts as an abrasive cutting jet at throttling velocities. Standard stainless steel trim may fail within weeks. These applications need tungsten carbide or ceramic seats and hardened plugs, or complete redesign using choke-style valves specifically engineered for erosive service.

Finally, throttle valves are inappropriate for flow metering or custody transfer. While a calibrated throttle valve can provide rough flow indication based on pressure drop and valve position, the nonlinear relationship between these parameters and the sensitivity to fluid properties (density, viscosity, temperature) make throttle valves unsuitable where accurate flow measurement is required. Dedicated flow meters (magnetic, ultrasonic, Coriolis) serve metering functions while throttle valves handle control.

Selecting the Right Throttle Valve: Engineering Calculations and Standards

Proper throttle valve selection requires quantitative analysis rather than rule-of-thumb sizing. The selection process begins with calculating the required flow coefficient.

For liquid service, first determine the necessary Cv using actual operating conditions at the valve's typical control point (usually 50-70% open):

For example, a water system requiring 100 GPM flow with 25 psi pressure drop needs: Cv = 100 × √(1.0/25) = 20. The engineer selects a valve size where this Cv value falls in the middle of the valve's range, ensuring adequate control authority at both higher and lower flow conditions.

Oversizing represents the most common selection error. Installing a valve with Cv = 100 in the example above would force the valve to operate at 10% opening to achieve the target flow. At this small opening, minor stem movement produces large flow changes, creating unstable control and potential oscillation. Additionally, the high velocity concentrated at the nearly-closed seat causes accelerated erosion. As a general principle, throttle valves should be sized to operate between 20% and 80% open under normal conditions, with the calculated Cv at 60% travel representing typical flow requirements.

Gas service calculations must account for compressibility and potential choked flow. When gas velocity reaches sonic conditions (Mach 1) at the vena contracta, flow becomes choked—further downstream pressure reduction cannot increase flow rate. The critical pressure ratio defines this limit:

The exact value depends on the gas ratio of specific heats and the valve's pressure recovery factor (FL). Sizing for choked gas service requires manufacturer software that accounts for these complex relationships.

Leak classification defines closed-valve tightness according to ANSI/FCI 70-2 standard, with six classes ranging from Class I (no test) to Class VI (bubble-tight soft seats). The selection depends on process requirements:

| Leak Class | Maximum Leakage Rate | Seat Type | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class II | 0.5% of valve capacity | Double-seated (balanced) | Non-critical utility services |

| Class IV | 0.01% of capacity | Metal-to-metal | Standard process control, most industrial applications |

| Class V | 0.0005 ml/min per inch diameter per psi ΔP | Metal-to-metal (precision) | High-performance control, reduced emissions |

| Class VI | Specific bubble count (drops/min) | Soft seated (PTFE, elastomer) | Tight shutoff, toxic/volatile services (requires separate isolation) |

Metal seats (Class IV) provide the best compromise for most throttle applications, offering acceptable leakage rates while withstanding high temperatures, erosion, and frequent cycling. Soft seats achieve Class VI bubble-tight shutoff but sacrifice temperature capability (PTFE limits around 400°F) and wear resistance. High-performance processes may specify Class V metal seats as a middle ground, though the tighter tolerances increase valve cost substantially.

Material selection must address the specific process chemistry, temperature range, and pressure requirements. Austenitic stainless steels (316/316L) serve as the default for general aqueous and mildly corrosive services. High-temperature steam systems use martensitic stainless (410) for hardness, chromium-molybdenum alloys, or even cast iron for low-pressure applications. Severe service trim may specify cobalt-chromium alloys (Stellite) or tungsten carbide for erosion and galling resistance. The valve body material must meet pressure-temperature ratings per ASME B16.34 standards, with flange connections conforming to ASME B16.5 dimensional standards.

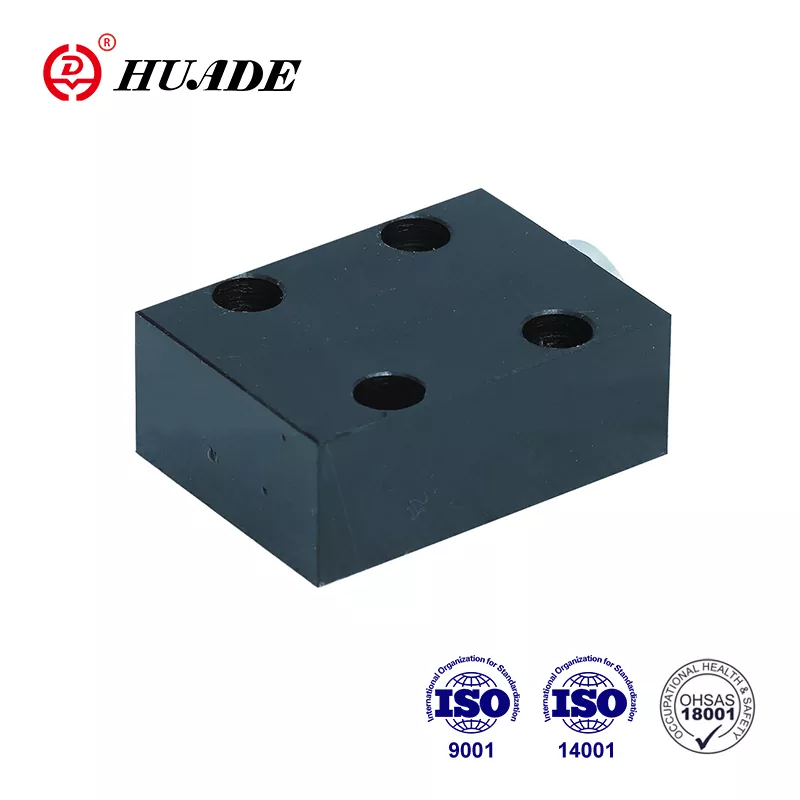

End connection type affects installation flexibility and maintenance accessibility. Flanged valves suit permanent installations in larger sizes (2 inches and up), providing easy removal for service. Threaded connections work for smaller valves (under 2 inches) in low-vibration applications, though thread sealant and proper thread engagement are critical. Socket weld or butt weld connections offer leak-tight permanent installation for critical services but eliminate any removal possibility without cutting pipes.

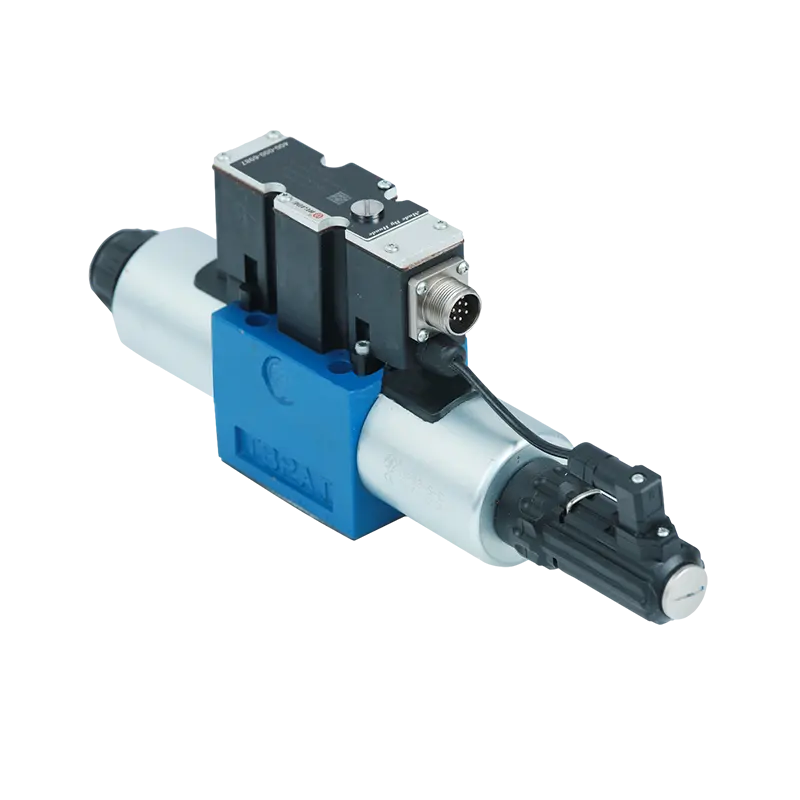

Actuator selection completes the throttle valve specification. Manual handwheels suffice for infrequent adjustment, but process control applications need automated actuation. Pneumatic spring-return diaphragm actuators provide fail-safe action (returning to a defined position on air loss) for control valves in process safety systems. Electric actuators (motor-driven) deliver precise positioning and eliminate compressed air requirements but lack inherent fail-safe behavior without adding spring modules or batteries. Hydraulic actuators generate maximum thrust for large valves or high-pressure differential applications where pneumatic cylinders cannot develop adequate stem force.

The engineer's valve selection documentation should include calculated Cv, specified trim type and materials, leakage class justification, actuator type with fail-safe mode, and conformance to applicable standards (ASME, API, ISA). This disciplined approach ensures the throttle valve matches the application's actual technical requirements rather than defaulting to arbitrary sizing or over-specification.