When technicians search for what makes up a flow control valve, they're usually trying to understand a specific type found in hydraulic and pneumatic systems. The answer reveals something interesting about engineering design: the most common flow control valve is actually a combination of two simpler components working together. This article explains what these components are, why engineers combine them, and how this combination solves real problems in industrial systems.

The Standard Answer: Throttle Plus Check

A flow control valve is most commonly a combination of a throttle valve (or needle valve) and a check valve. This combination creates what engineers call a "one-way flow control valve" or "unidirectional flow control valve."

The throttle valve restricts flow in both directions when used alone. The check valve allows free flow in one direction while blocking flow in the opposite direction. When you combine these two components in parallel within a single valve body, you get controlled flow in one direction and unrestricted flow in the other.

Why Engineers Don't Just Use a Simple Throttle

A basic throttle valve creates resistance in both directions. In a drilling machine, this would mean the drill advances slowly (good) but also retracts slowly (bad). The combined valve solves this by allowing slow feed and fast return.

The physics involves flow equations. For a simple orifice, flow rate $Q$ follows:

$$ Q = C_d \cdot A \cdot \sqrt{\frac{2\Delta P}{\rho}} $$Where $C_d$ is the discharge coefficient, $A$ is orifice area, $\Delta P$ is pressure drop, and $\rho$ is fluid density. Without the check valve bypass, this restriction applies to both directions.

How the Components Work Together

The valve body contains two parallel flow paths:

- Controlled Direction: Pressure pushes the check valve closed. All flow must pass through the narrow throttle. Flow rate is user-adjustable (0-100 L/min).

- Free-Flow Direction: Pressure opens the check valve (cracking pressure ~0.03-0.05 MPa). Most fluid bypasses the throttle, dropping resistance to nearly zero.

| Flow Direction | Active Component | Typical Flow Rate | Pressure Drop |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled (throttled) | Needle valve | User-adjustable (0-100 L/min) | 0.5-3 MPa |

| Free (bypass) | Check valve | Limited only by line size | 0.03-0.05 MPa |

Meter-In vs Meter-Out Control

Meter-Out (Exhaust Throttling): Restricts flow leaving the actuator. Creates back pressure to prevent jerky motion. Standard for pneumatics.

Meter-In (Inlet Throttling): Restricts flow entering the actuator. Prevents runaway loads (e.g., lowering heavy weights). Standard for specific hydraulic gravity loads.

Note: You can switch strategies simply by reversing the valve orientation.

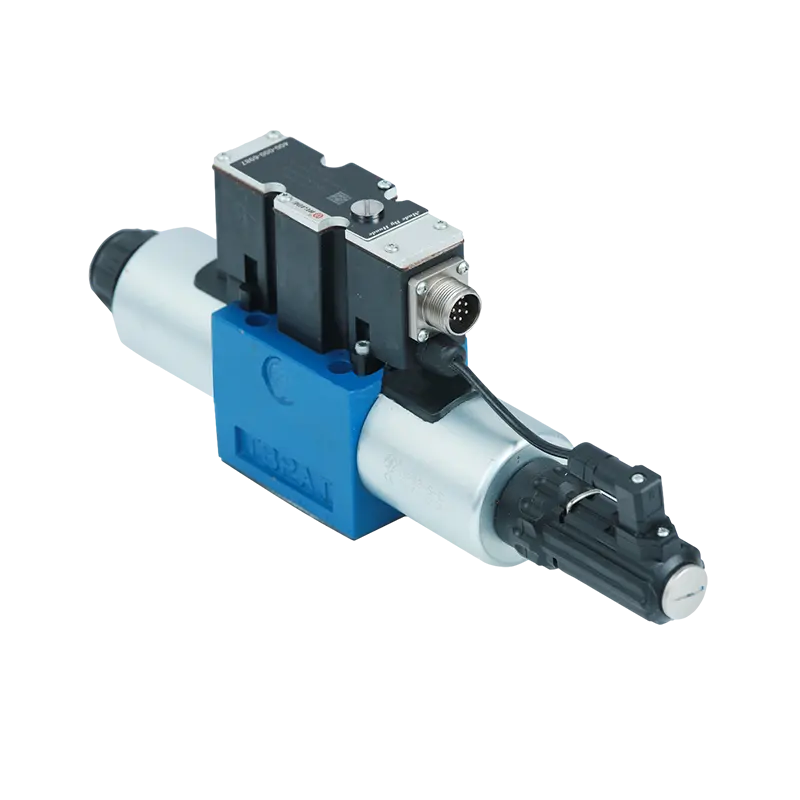

Physical Construction and Materials

Body: Cast iron (hydraulics) or aluminum (pneumatics).

Needle: Tapered steel pin (8-15° angle) for fine adjustment.

Check Valve: Ball or poppet design with a light spring (2-5 N).

Seals: NBR for standard oil (-20°C to +80°C), FKM/Viton for high temp/aggressive fluids.

Advanced Combinations: Adding Pressure Compensation

Basic throttle-check valves suffer from flow variation ($\pm 15\%$) when load pressure changes. Pressure-compensated valves add a third component: a compensator spool.

This spool automatically adjusts its opening to maintain a constant pressure drop across the throttle, keeping flow stable ($\pm 2\%$) regardless of load changes. Temperature compensation (using sharp-edged orifices or bimetallic elements) further stabilizes flow against viscosity changes.

| Valve Type | Combination | Flow Stability | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic throttle-check | Needle + Check | ±15% | Pneumatics, simple hydraulics |

| Pressure-compensated | Needle + Check + Compensator | ±2% | Precision hydraulics |

| Temperature-compensated | Needle + Check + Bimetal | ±3% | Aerospace, mobile equipment |

Troubleshooting and Applications

Common Issues:

- Drift in one direction: Stuck check valve (debris).

- Inconsistent speed: Stuck compensator spool (contamination).

- Leakage at adjustment: Worn O-rings.

Applications: From manufacturing press cylinders (meter-out) to mobile excavator circuits and automated assembly lines. Understanding that these valves are engineered combinations helps in selecting the right type—basic for pneumatics, compensated for precision hydraulics.