Pressure valves are the unsung heroes of modern industrial systems. Every day, these devices prevent catastrophic failures in everything from home water heaters to massive oil refineries. When system pressure climbs beyond safe limits, a pressure valve opens to release fluid and protect equipment. Without them, pressurized systems would be ticking time bombs.

This guide breaks down the complex world of pressure valves into practical knowledge. Whether you're troubleshooting a leaking valve, selecting the right type for your application, or trying to understand the difference between a PSV and PRV, you'll find clear answers rooted in engineering fundamentals and industry standards.

What is a Pressure Valve and How Does It Work

A pressure valve controls or limits pressure within a fluid system by releasing excess pressure when it exceeds a predetermined setpoint. The core principle is straightforward: spring force holds the valve closed until fluid pressure generates enough force to overcome the spring and lift the valve disc. Once open, fluid escapes until pressure drops below the closing point, and the spring reseats the valve.

The critical engineering balance happens at the valve disc. On one side, spring compression creates a closing force. On the other side, fluid pressure acting on the disc area creates an opening force. When the opening force exceeds the closing force, the valve lifts. This relationship follows the basic equation: Pressure × Disc Area = Spring Force at setpoint.

Modern pressure valves incorporate sophisticated features beyond this simple force balance. The huddling chamber design, found in many safety valves, creates a sudden "pop" action. As the valve begins to lift, fluid rushes into an expansion chamber beneath the disc. This chamber has a larger surface area than the inlet, so the same pressure now acts on a bigger area. The result is an immediate increase in lifting force that snaps the valve fully open. This pop action is critical for gas and steam services where gradual opening could allow dangerous pressure buildup.

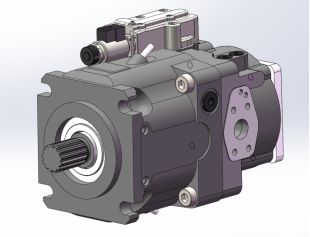

Direct-acting pressure valves rely entirely on spring force for closure, making them simple and reliable. The spring sits directly on top of the valve disc or stem. These valves respond quickly to pressure changes but have limitations. They can be affected by back pressure on the outlet side, and they may "simmer" (slight leakage) when operating pressure approaches the setpoint because closing force becomes minimal.

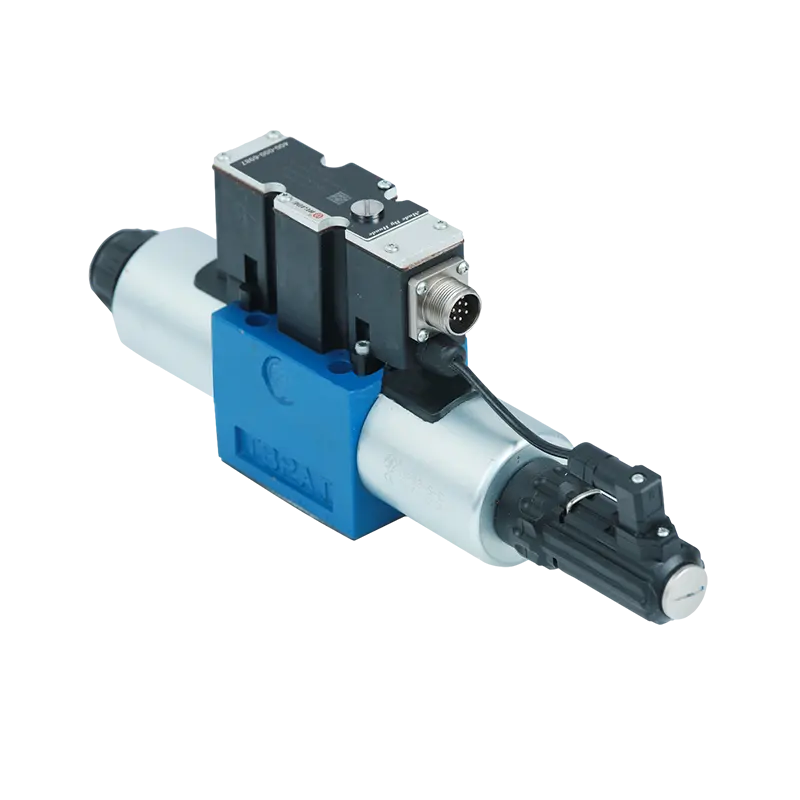

Pilot-operated pressure valves solve many direct-acting limitations through clever engineering. A small pilot valve controls pressure in a dome chamber above the main valve piston. System pressure feeds into both the inlet and the dome, but the dome has a larger surface area. This means the main valve stays tightly sealed with zero leakage even at 98% of setpoint pressure. When pressure reaches the setpoint, the pilot valve vents the dome to atmosphere. The pressure imbalance opens the main valve. This design excels in high-pressure applications and situations with variable back pressure.

Types of Pressure Valves: Understanding the Critical Differences

The terms "pressure safety valve," "pressure relief valve," and "pressure reducing valve" are often used interchangeably, but they serve fundamentally different functions. Mixing them up in your system can lead to equipment damage or worse.

Pressure Safety Valves (PSV)

Pressure safety valves are designed specifically for compressible fluids like steam, gases, and vapors. The defining characteristic is their snap action or "pop" opening behavior. When system pressure hits the setpoint, the valve doesn't gradually crack open. Instead, it slams to full lift in milliseconds.

This rapid full-stroke opening happens because of the huddling chamber or reaction lip design. As the disc begins to lift, expanding gas flows into a chamber where it acts on a larger surface area. The sudden increase in lifting force causes the valve to pop completely open. The valve stays wide open until pressure drops significantly below the setpoint, typically by 2-4%. This pressure difference between opening and closing is called blowdown.

The pop action and large blowdown are not design flaws. They're essential safety features for gas systems where pressure can rise exponentially. A slowly opening valve wouldn't relieve pressure fast enough to prevent an explosion in a gas-filled vessel. The rapid opening dumps massive volume quickly, killing the pressure spike before it becomes catastrophic.

PSVs commonly operate at 3% overpressure for single-valve installations per ASME Section I requirements. This means if your vessel's maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP) is 100 psi, the safety valve setpoint might be 100 psi, but the system pressure will reach 103 psi before the valve fully relieves.

Pressure Relief Valves (PRV)

Pressure relief valves are the workhorses for incompressible fluids, primarily liquids like water, oil, and hydraulic fluid. Unlike PSVs, PRVs open proportionally to pressure increase. As pressure rises above setpoint, the disc lifts gradually. Flow rate through the valve increases proportionally with the pressure overshoot.

This proportional action prevents water hammer, the destructive pressure wave that occurs when liquid flow stops suddenly. If you installed a pop-action PSV on a liquid line and it suddenly opened, the rapid pressure drop could create shock waves that crack pipes and destroy fittings. The PRV's gradual opening and closing protects piping systems from these hydraulic shocks.

PRVs typically operate with 10% or 25% allowable overpressure depending on the code (ASME Section VIII allows 10% for a single valve). The closing action is equally gradual, with the valve reseating smoothly as pressure drops back toward setpoint.

| Characteristic | Pressure Safety Valve (PSV) | Pressure Relief Valve (PRV) |

|---|---|---|

| Fluid Type | Compressible (gas, steam, vapor) | Incompressible (liquid, oil, water) |

| Opening Action | Rapid "pop" to full lift | Gradual, proportional to pressure |

| Mechanism | Huddling chamber creates lift amplification | Simple force balance (spring vs. hydraulic pressure) |

| Closing Behavior | Rapid closure after blowdown (2-4% typical) | Progressive reseating as pressure decreases |

| Primary Hazard Prevented | Explosive gas expansion | Hydraulic rupture/overpressure |

| Typical Overpressure | 3% or 10% (depends on code) | 10% or 25% (depends on code) |

Pressure Reducing Valves

Pressure reducing valves serve an entirely different function than safety or relief valves. While safety valves are normally closed and only open during overpressure emergencies, reducing valves are normally open control devices. They throttle flow to maintain a constant downstream pressure regardless of upstream pressure variations or flow demand changes.

Direct-acting reducing valves use downstream pressure working against a spring-loaded diaphragm or piston. If downstream pressure rises, it compresses the spring and closes the valve element. If downstream pressure drops, the spring pushes the valve more open. These valves are cost-effective but experience "droop" (pressure drop) under high flow conditions because the spring-diaphragm system has limited force capacity.

Pilot-operated reducing valves deliver superior accuracy by using a small pilot valve to load the main valve diaphragm. This amplification of control force allows the valve to maintain tight downstream pressure tolerances even with massive flow swings. You'll find pilot-operated reducing valves in chemical processing plants, natural gas distribution networks, and large water supply systems where precision pressure control is non-negotiable.

Common Pressure Valve Problems and Troubleshooting

Understanding failure modes helps you diagnose issues quickly and implement correct fixes rather than expensive trial-and-error repairs.

Valve Chattering

Chattering is the rapid, violent opening and closing of a pressure relief valve. The sound is distinctive: a machine-gun rattling that can be heard across an entire facility. This failure mode is widely considered the most destructive because it hammers the valve seat and can pulverize valve internals within hours.

Oversizing is the most common cause of chattering. When you install a valve with too much flow capacity for the actual relief load, it opens and instantly drops system pressure below the closing point. The valve slams shut. Pressure rebuilds immediately and the cycle repeats hundreds of times per minute. The solution requires replacing the valve with a smaller orifice size that matches the actual relief requirement.

Excessive inlet pressure drop also causes chattering through a different mechanism. API 520 Part 2 specifies that piping pressure loss between the protected vessel and valve inlet must not exceed 3% of set pressure. If inlet line losses are higher, here's what happens: The valve opens, flow begins, and pressure at the valve inlet drops below closing pressure due to pipe friction losses. The valve closes. Flow stops, pressure recovers, and the valve reopens. This cycle continues until something breaks. The fix requires increasing inlet pipe diameter or relocating the valve closer to the vessel.

High back pressure in the discharge system can also trigger chattering. When discharge pressure pushes back against the valve disc, it effectively adds to the closing force. The valve's actual opening pressure becomes higher than its set pressure. As soon as the valve opens and flow begins, discharge pressure spikes from sudden flow, and the valve snaps shut. Installing a pilot-operated valve or bellows-sealed valve eliminates back pressure effects on valve performance.

Valve Seat Leakage (Simmering)

Leakage before the valve reaches set pressure is called simmering. You'll see steam wisps from a safety valve vent or hear a continuous hissing sound. This condition wastes product, violates environmental emission limits, and progressively damages the seat through erosion and wire-drawing.

Operating too close to set pressure is a primary cause. ASME Section VIII recommends operating at least 10% below set pressure. When you operate at 98% of set pressure, closing force becomes nearly zero. Any vibration, thermal expansion, or minor pressure spike can momentarily lift the disc and start the leak. Once leakage begins, the escaping high-velocity fluid cuts a groove in the soft seat metal. The leak becomes permanent. Lowering operating pressure or increasing the valve set pressure (if safe) stops simmering before seat damage occurs.

Debris on the seat is another common source. Dirt, weld slag, pipe scale, or gasket material particles lodge between the disc and seat, preventing tight closure. During new system startup, construction debris is almost guaranteed unless extensive flushing procedures were followed. The solution involves removing the valve and manually inspecting and cleaning the seat and disc. Lapping compound can restore the sealing surface if damage is minor, but deep grooves require replacement parts.

Misalignment of the valve stem or guides causes uneven loading on the seat. If the disc doesn't sit perfectly flat, it will leak. This is particularly common after rough handling during installation or maintenance. Checking spindle verticality and guide clearances usually identifies the problem.

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Valve Chattering | Valve oversized for actual relief load | Replace with smaller orifice valve |

| Valve Chattering | Inlet pressure drop exceeds 3% of set pressure | Increase inlet pipe diameter or relocate valve |

| Valve Chattering | Excessive back pressure | Switch to pilot-operated or bellows valve |

| Simmering (Leakage) | Operating pressure too close to setpoint | Lower operating pressure or increase setpoint if safe |

| Simmering (Leakage) | Debris on seat or disc damage | Dismantle, clean, lap seat or replace damaged parts |

| Simmering (Leakage) | Valve stem misalignment | Check and correct spindle verticality |

| Fails to Open | Corrosion welding disc to seat | Remove valve, dismantle, and chemically clean |

| Fails to Open | Chemical scaling or polymerization | Remove and chemically clean or replace internals |

| Fails to Open | Mechanical damage (bent stem) | Replace damaged components |

| Low Opening Pressure | High ambient temperature | Adjust cold differential test pressure (CDTP) |

| Low Opening Pressure | Spring relaxation or fatigue | Replace spring |

Failure to Open

This is the most dangerous failure mode because the pressure valve fails to perform its primary safety function. When pressure reaches dangerous levels and the valve remains closed, you have seconds before catastrophic failure occurs.

Corrosion is the leading cause of stuck valves. When a carbon steel valve sits idle for months in a humid or corrosive environment, rust forms at the disc-to-seat interface. The oxide literally welds the surfaces together. By the time overpressure occurs, the spring force is insufficient to break the corrosion bond. The valve never opens. Preventing this requires regular lift testing using the manual lever, but only when system pressure is at least 75% of set pressure to avoid seat damage from forcing the disc open against full spring compression.

Chemical scaling and polymerization cause similar sticking. Process fluids can leave deposits that harden over time. This is particularly common in hydrocarbon services where polymerization gradually glues the valve shut. Regular removal and bench testing is the only reliable prevention method for critical services.

Mechanical damage like bent stems or jammed guides also prevents opening. This typically results from improper installation, rough handling, or freeze damage in outdoor installations. Physical inspection during scheduled maintenance identifies these issues before they become critical.

Pressure Valve Selection and Sizing Guidelines

Choosing the wrong pressure valve is worse than having no valve at all because it creates a false sense of security. Proper selection requires matching valve characteristics to service conditions and calculating required relieving capacity.

Determining Required Relief Capacity

The first step in valve selection is calculating the relieving load, the mass flow rate the valve must handle during the worst-case overpressure scenario. This requires process knowledge that goes beyond simple system volume. API 521 provides calculation methodologies for different scenarios.

Fire exposure on a pressure vessel generates enormous vapor volumes as heat vaporizes liquid contents. The API 521 fire relief calculation considers vessel surface area exposed to flame, insulation type, and fluid properties. A typical fire case might require relieving 50,000 pounds per hour of propane vapor from a storage tank. Undersizing this valve even slightly means the vessel will rupture before adequate relief occurs.

Cooling system failure in a chemical reactor can cause runaway reactions that generate massive gas volumes. The relief calculation must account for reaction kinetics, heat generation rate, and vapor production. This is where chemical engineers earn their pay because relief load calculations for reactive systems require detailed thermodynamic modeling.

Blocked discharge scenarios occur when a pump continues running with a closed valve downstream. The pressure relief valve on the pump discharge must handle full pump flow at shutoff head. This is typically a liquid service requiring PRV rather than PSV selection.

Orifice Sizing and Flow Coefficients

Once you know the required relieving capacity, you select valve orifice size using API 520 Part 1 sizing equations. For gas and vapor service, the equation accounts for compressibility effects, molecular weight, temperature, and the valve's certified flow coefficient. The calculation determines the minimum required effective discharge area.

API 526 standardizes orifice designations from D through T, with each letter representing a specific orifice area. This standardization allows direct replacement between manufacturers. A "J" orifice is a "J" orifice whether you buy from Crosby, Anderson Greenwood, or Leser. The actual dimensions are published in API 526 tables.

Critical pressure ratio affects gas valve sizing. When downstream pressure drops below 50-60% of upstream pressure (depending on gas properties), flow reaches sonic velocity at the valve throat. The flow becomes "choked" and cannot increase further regardless of how much lower the downstream pressure drops. Sizing equations account for this compressibility effect. Ignoring it leads to dangerous undersizing.

Liquid valve sizing follows different principles since liquids are essentially incompressible. The sizing equation relates flow rate to pressure drop across the valve using a discharge coefficient. The calculation is simpler than gas sizing but still requires careful attention to viscosity effects and potential flashing if pressure drop causes liquid to vaporize.

Material Selection for Service Conditions

Material compatibility determines valve reliability and longevity. Standard carbon steel valves work fine for non-corrosive, moderate-temperature applications. But extreme conditions require specialty materials.

Hydrogen service demands special metallurgy due to hydrogen embrittlement. Hydrogen atoms diffuse into steel crystal structures and reduce ductility, causing brittle fracture under stress. High-strength steels like 440C have failed catastrophically in hydrogen PRV nozzles. Austenitic stainless steels like 316L offer better resistance, but even these require careful selection. For hydrogen refueling stations, valves must survive 102,000 pressure cycles across temperature ranges from -40°C to +85°C. Standard materials simply cannot meet these demands.

High-temperature steam service requires materials that maintain strength above 450°C. Chrome-moly alloys like SA-217 Grade WC9 are common choices. The spring must also withstand the temperature, often requiring Inconel or other high-temperature alloys rather than carbon steel.

Corrosive services may require exotic alloys. Monel (nickel-copper) resists seawater and hydrofluoric acid. Hastelloy (nickel-molybdenum-chromium) handles hot sulfuric acid and chlorine gas. These specialty materials drive valve costs up significantly, but failure costs far more.

Installation and Maintenance Best Practices

Even perfectly selected valves fail without proper installation and maintenance. Following industry standards prevents most common problems.

``` [Image of correct piping installation diagram for pressure safety valve] ```Installation Guidelines

Inlet piping must minimize pressure drop to prevent chattering. API 520 Part 2 specifies maximum 3% pressure loss from vessel to valve inlet. This means short, large-diameter piping with minimal elbows and fittings. A common mistake is necking down from a 4-inch vessel connection to a 2-inch valve inlet using a reducer. The pressure loss through that reducer can easily exceed 3% at full flow, guaranteeing chatter problems.

Discharge piping requires different considerations. For PSVs venting to atmosphere, discharge lines should slope away from the valve to drain condensate. Water pooling in the discharge piping can freeze in cold weather and block the line. The discharge line must have larger diameter than the valve outlet to keep back pressure below the valve's rating. Manufacturers publish maximum allowable back pressure values, typically 10% of set pressure for conventional valves.

Pilot-operated valves tolerate higher back pressure, up to 50% of set pressure in some designs, because back pressure doesn't affect the closing force. This makes them ideal for systems with long discharge headers or shared flare headers where back pressure varies with other valves' operation.

Support the valve independently from piping. The valve should not bear the weight of inlet or discharge piping. Pipe stress can misalign the valve internals and cause leakage or binding. Use properly designed pipe supports adjacent to the valve.

Maintenance Intervals and Testing

Most jurisdictions require periodic pressure relief valve testing. The interval depends on service severity and regulatory requirements. Clean, non-corrosive services might allow 5-year test intervals. Dirty, corrosive, or fouling services require annual or more frequent testing.

In-situ testing uses hydraulic assist tools to lift the valve while it remains installed. This verifies that the disc is free to move and can crack open. However, in-situ testing cannot verify seat tightness or actual set pressure accuracy. It's a basic operational check, not a comprehensive certification.

Bench testing in a certified shop provides complete verification. The valve is removed, disassembled, cleaned, inspected, reassembled, and then tested on a test stand. The test stand gradually increases pressure while monitoring for leakage. When the valve pops open, the opening pressure is recorded. This must fall within ±3% of nameplate set pressure per ASME requirements. Then the valve reseats and the closing pressure is recorded to verify proper blowdown. Finally, seat tightness is tested per API 527, which specifies allowable bubble rates for different valve sizes.

After passing bench testing, the valve receives a new certification tag showing test date, set pressure, and test facility. This documentation proves compliance during regulatory inspections.

Industry Standards and Compliance Requirements

Pressure valve design, testing, and application are governed by multiple standards organizations. Understanding these requirements is not optional; it's legally mandated in most industrial facilities.

ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers publishes the definitive pressure vessel safety standards for North America and many other regions. ASME BPVC Section I covers fired boilers where steam explosions pose catastrophic risks. Requirements are stricter here than anywhere else.

Section I valves must have the "V" stamp, meaning they were manufactured under strict ASME quality control and tested by an authorized inspector. These valves require specific blowdown control, typically 2 psi or 2% minimum, achieved through careful adjustment ring design. The allowable accumulation (pressure rise above MAWP) is limited to 3% for a single valve or 5% for multiple valves. This tight control prevents dangerous pressure spikes.

ASME Section VIII covers unfired pressure vessels like chemical reactors, storage tanks, and compressed gas cylinders. Section VIII valves carry the "UV" stamp and have more relaxed requirements than Section I. Accumulation is allowed up to 10% for a single valve or 16% for multiple valves. Blowdown is not strictly mandated.

The critical point many engineers miss: Section VIII valves cannot be used on Section I boilers. Section VIII valves lack the mandatory blowdown control features of Section I valves, which would cause dangerous chattering and potential valve destruction in steam boiler service. This specification mismatch has caused serious accidents.

| Requirement | ASME Section I (Power Boilers) | ASME Section VIII (Pressure Vessels) |

|---|---|---|

| Application | Fired steam boilers | Unfired pressure vessels |

| Certification Mark | "V" Stamp | "UV" Stamp |

| Blowdown Requirement | Mandatory minimum (2 psi or 2%) | No mandatory minimum |

| Allowable Accumulation | 3% (single valve), 5% (multiple) | 10% (single valve), 16% (multiple) |

| Construction Features | Typically requires dual adjustment rings | Single adjustment ring or fixed design acceptable |

API Standards for Petroleum Industry

While ASME provides construction rules and stamping requirements, the American Petroleum Institute provides practical guidelines for selection, sizing, and operation in oil and gas facilities.

API 520 is the sizing bible. Part 1 provides calculation formulas for steam, gas, liquid, and two-phase flow conditions. Part 2 covers installation details critical for preventing inlet pressure loss and managing back pressure. These are the documents valve engineers reference daily when designing relief systems.

API 521 focuses on system design rather than valve selection. It guides calculation of relief loads for various scenarios: fire exposure, cooling water failure, runaway reactions, thermal expansion, and vapor blowby. API 521 defines the scenarios your valve must handle.

API 526 standardizes physical dimensions and pressure-temperature ratings for flanged steel safety relief valves. This standardization enables interchangeability between manufacturers. You can replace a failed valve with any API 526-compliant equivalent without modifying piping.

API 527 defines seat tightness test procedures and acceptance criteria. It specifies allowable bubble rates during bench testing. This quantifies what "leak-tight" actually means in measurable terms rather than subjective judgment.

API 576 provides inspection and testing guidelines for refinery and chemical plant pressure relief devices. It details failure mechanisms (corrosion, scaling, erosion) and prescribes inspection intervals and methods. This is the operational companion to the design standards.

Environmental and Fugitive Emission Standards

Pressure valves historically were a major source of fugitive emissions, the unintended leaks that release volatile organic compounds and greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Modern environmental regulations are forcing dramatic improvements in valve sealing technology.

API 624 covers stem seal testing for rising stem valves like gate and globe valves. The valve must survive 310 mechanical cycles plus thermal cycles with less than 100 ppm methane leakage detected. This is a pass/fail type test that eliminates poor designs.

ISO 15848 takes this further with different "endurance classes." A Class CO3 valve must survive 2,500 mechanical cycles while maintaining seal integrity. This standard uses helium leak detection for extreme sensitivity. Meeting ISO 15848 requires "Low-E" (low emission) packing technology, typically involving live-loaded packing systems with Belleville spring washers that maintain constant packing pressure as materials compress over time.

These fugitive emission standards aren't optional in many jurisdictions. European Union regulations, US EPA requirements, and corporate environmental policies increasingly mandate Low-E certified valves for all new installations and existing valve replacements.

Applications Across Different Industries

Pressure valves serve vastly different functions across industrial sectors, and understanding application-specific requirements helps in proper selection.

Water and HVAC Systems

Residential and commercial water systems use pressure reducing valves to step down high municipal supply pressure to safe building levels. City water might arrive at 120 psi, but building piping and fixtures are rated for 80 psi maximum. A pressure reducing valve at the building entrance throttles flow to maintain constant 60-70 psi downstream regardless of upstream fluctuations or flow demand.

Water heater safety valves prevent explosion from thermostat failure. If the thermostat sticks and heating continues indefinitely, water temperature rises and steam pressure builds rapidly. The temperature-pressure relief valve (TPRV) mounted on top of the tank opens at 150 psi or 210°F, whichever comes first. This simple device prevents thousands of potential explosions annually.

Cavitation damage is a major concern in high-pressure water systems. When water velocity increases through a pressure reducing valve, static pressure drops. If pressure falls below the vapor pressure of water, bubbles form. As flow slows downstream and pressure recovers, these bubbles implode violently. The collapsing bubbles generate focused jets of liquid moving at hundreds of meters per second. These microjets erode metal from the valve body in a process called pitting. Stage pressure drops using two valves in series or use special anti-cavitation trim designs that break the pressure drop into many small stages and move bubble collapse away from metal surfaces.

Chemical Processing and Refineries

Chemical plants demand pressure valves that handle corrosive, toxic, and reactive materials. Material selection becomes paramount. A valve that works fine in steam service will fail rapidly in sulfuric acid or chlorine gas.

Thermal relief valves protect blocked-in liquid systems. If a section of pipe filled with liquid gets isolated between closed valves and then heated by sun or process heat, thermal expansion creates enormous pressure. Liquids are essentially incompressible, so even a few degrees of temperature rise can generate pressures that burst piping. Small thermal relief valves sized for liquid expansion volumes provide this protection.

Runaway reaction scenarios require careful analysis of relieving requirements. An exothermic reaction with failed cooling can generate gas at accelerating rates. The relief valve must handle not just normal vapor production but also the worst-case vapor generation from the runaway reaction. These calculations require detailed reaction kinetics knowledge and conservative assumptions about cooling system failures.

Oil and Gas Production

Wellhead pressure safety valves protect against sudden formation pressure surges. Production tubing operates at high pressure, and equipment failure can cause sudden pressure spikes. PSVs sized for full formation flow capacity provide the last line of defense against blowouts.

Flare systems collect relief valve discharges from across an entire facility. Multiple pressure valves discharge into shared headers that route all releases to a flare tip where hydrocarbons burn rather than releasing directly to atmosphere. The flare header operates at variable back pressure depending on which valves are flowing. This requires careful engineering to ensure individual valve back pressure ratings aren't exceeded when multiple valves operate simultaneously.

Offshore platforms face unique challenges from weight and space constraints. Every pound of equipment must be lifted by crane or helicopter. This drives demand for compact, lightweight valve designs. Subsea applications add the complication of cold seawater temperatures and high ambient pressures. Specialty materials and designs address these extreme conditions.

Hydrogen and Alternative Fuels

The push toward hydrogen economy presents unprecedented challenges for pressure valve technology. Hydrogen molecules are tiny enough to diffuse into metal crystal lattices, causing hydrogen embrittlement that reduces material ductility. High-strength steels that work perfectly in natural gas service crack catastrophically in hydrogen.

Hydrogen refueling stations require pressure valves rated for 700 bar (10,000 psi) service with extreme thermal cycling from -40°C to +85°C. Standard materials cannot survive 102,000 pressure cycles under these conditions. New austenitic stainless steel alloys and specialized testing protocols are being developed specifically for hydrogen applications.

Seal materials also require redesign for hydrogen. Standard elastomers allow excessive hydrogen permeation. The hydrogen gas dissolved in the seal material can cause explosive decompression when pressure drops rapidly. The dissolved gas expands faster than it can escape, literally tearing the seal apart. This requires specialty seal compounds resistant to permeation and explosive decompression.

The pressure valve industry stands at the intersection of mechanical engineering tradition and digital innovation. While core physics remains unchanged, the context in which these devices operate has transformed. Modern engineers must size valves using API 520 while simultaneously selecting hydrogen-compatible materials resistant to embrittlement, ensuring seals meet fugitive emission standards like API 624 and ISO 15848, and considering integration of acoustic monitoring for predictive maintenance.

Smart pressure valves equipped with IoT sensors are no longer isolated mechanical sentinels but communicating nodes in plant-wide safety instrumented systems. Data analytics predict seal failures 45-75 days in advance, shifting maintenance paradigms from reactive repairs to condition-based interventions that save millions in downtime costs.

As industries transition toward sustainability, pressure valves will play an outsized role in ensuring that next-generation energy carriers, from hydrogen to ammonia, are handled with the same rigor and safety that protected steam and petroleum systems. Market success will belong to manufacturers who combine advanced metallurgy with low-emission sealing technology and intelligent diagnostics, delivering not just hardware but complete safety solutions for the next era of industrial infrastructure.