When engineers design pressure relief systems, they follow rules that prevent equipment failures and protect people. One of the most important rules in this field is the "3% rule" for pressure relief valve inlet piping. This rule appears in major engineering standards like API 520 and ASME Section VIII, and understanding it properly can mean the difference between a safe system and a dangerous one.

The 3% rule states that the total non-recoverable pressure loss in the inlet piping leading to a pressure relief valve should not exceed 3% of the valve's set pressure. In simpler terms, when fluid flows through the pipe toward the relief valve, friction and turbulence cause some pressure to drop. This pressure drop must stay below 3% of the pressure at which the valve is designed to open.

This seemingly simple percentage actually addresses a complex problem in fluid dynamics. When a relief valve opens, it needs a steady supply of fluid at sufficient pressure to stay open and do its job. If the inlet pipe causes too much pressure loss, the valve can start chattering, which means it rapidly opens and closes. This chattering can destroy the valve seat, damage connected piping, and create dangerous situations in industrial facilities.

Why the 3% Limit Exists

The engineering reason behind the 3% rule connects directly to how spring-loaded relief valves work. These valves have a blowdown characteristic, which is the difference between the set pressure and the reseating pressure. Most API 520 compliant valves have a blowdown of 7% to 10% of set pressure.

When the valve opens fully, fluid rushes through the inlet pipe at high velocity. This flow creates friction losses that reduce the pressure right at the valve inlet. If this pressure drop becomes too large, the pressure at the valve disc falls below the reseating pressure even though the protected equipment is still overpressured.

When this happens, the spring force pushes the disc back onto the seat, cutting off flow. As soon as flow stops, the friction losses disappear and pressure recovers, causing the valve to open again. This cycle repeats at frequencies between 50 to 300 Hz, creating severe mechanical vibration.

The 3% threshold provides a safety margin. It keeps the inlet pressure loss smaller than the typical blowdown range, which helps ensure stable valve operation. For example, if a valve has a set pressure of 100 psig and a blowdown of 7%, it reseats at 93 psig. If the inlet loss is limited to 3% (3 psi), the pressure at the valve during flow will be 97 psig, which remains safely above the reseating pressure.

Research by organizations like ioMosaic and the Pressure Equipment Research Forum (PERF) has shown that inlet pressure loss interacts with valve spring characteristics and acoustic effects in the piping. These studies confirm that while 3% is not a physical law, it represents a practical threshold based on decades of field experience with conventional spring-loaded valves.

What Counts as Pressure Loss

The 3% rule specifically applies to non-recoverable pressure losses. Engineers need to understand what this includes and excludes.

Non-recoverable losses come from friction between the fluid and pipe walls, turbulence at fittings like elbows and tees, and entrance effects where fluid enters the pipe from a vessel. These losses permanently reduce the fluid's pressure energy and convert it to heat. The calculation uses the Darcy-Weisbach equation, which accounts for pipe length, diameter, friction factor, and fitting resistance coefficients.

What the 3% rule does not include is static head changes. If the relief valve sits higher than the protected vessel, the hydrostatic pressure difference is a recoverable loss. While this affects the valve set pressure determination, it does not count toward the 3% inlet loss limit. Similarly, velocity head changes in straight sections without area reductions are typically recoverable.

The entrance loss coefficient deserves special attention because it significantly affects short inlet lines. A sharp-edged entrance where pipe connects flush to a vessel nozzle has a resistance coefficient K of approximately 0.5. Engineers can reduce this to about 0.1 by using a rounded or bell-mouth entrance. For a 2-inch inlet line carrying 10,000 lb/hr of steam, this difference alone can account for 1% to 2% of set pressure, making it critical for meeting the 3% limit.

Calculating Inlet Pressure Drop

The proper method for calculating inlet pressure loss follows established hydraulic engineering principles, but several details often cause confusion in practice.

The most critical decision is choosing the correct flow rate for the calculation. API 520 Part II clearly states that engineers should use the valve's rated capacity, not the required relieving capacity for the specific scenario. This distinction matters because relief valves, especially conventional spring-loaded types, snap fully open when they lift. At full lift, the flow through the inlet pipe is determined by the valve's throat area, not by the upstream overpressure scenario.

If an engineer calculates inlet loss using the smaller required capacity instead of the rated capacity, they will underestimate the actual pressure drop that occurs when the valve opens. A valve might be sized for 15,000 lb/hr based on the worst-case scenario, but if its rated capacity at full lift is 25,000 lb/hr, the inlet pipe must be checked at 25,000 lb/hr to properly evaluate stability.

For gas and vapor systems, the calculation must account for density changes along the pipe length as pressure drops. As fluid moves toward the valve and pressure decreases, the gas expands, velocity increases, and additional pressure drop occurs. This creates a nonlinear relationship that simple hand calculations can miss. Software tools like Emerson PRV2SIZE or ioMosaic SuperChems handle these iterations automatically.

Liquid systems require different considerations. While liquids are incompressible, they have higher densities that create larger pressure drops at equivalent velocities. Viscosity effects become important for heavy oils or polymer solutions, where the Reynolds number may be low enough to significantly increase the friction factor. The Colebrook-White equation or Moody diagram provides the friction factor based on Reynolds number and relative pipe roughness.

For two-phase flow situations, which can occur during runaway reactions or thermal relief scenarios, engineers must use specialized correlations. The homogeneous equilibrium model (HEM) or the Omega method recommended by the Design Institute for Emergency Relief Systems (DIERS) calculates the integrated pressure drop accounting for vapor generation and slip between phases.

| Component | K Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sharp-edged entrance | 0.5 | Flush connection to vessel |

| Rounded entrance (r/D = 0.1) | 0.1 | Smooth transition reduces loss |

| 90° standard elbow | 30-40 fD | Equivalent length method |

| 45° elbow | 16 fD | Less resistance than 90° |

| Gate valve (fully open) | 8 fD | Should be locked open |

| Reducer (sudden contraction) | 0.5 × (1 - β²)² | β = diameter ratio |

When the 3% Rule Can Be Exceeded

The engineering standards that establish the 3% rule also recognize that it is not an absolute physical limit. Starting with the 1994 edition, API 520 Part II introduced provisions for exceeding 3% through what it calls "engineering analysis."

This engineering analysis approach acknowledges that the 3% threshold is a simplified screening criterion. Some systems with inlet losses above 3% can still operate stably, while others with losses below 3% might experience problems due to acoustic resonance or other dynamic effects not captured by a static pressure drop calculation.

A proper engineering analysis for exceeding 3% involves two main components: force balance analysis and acoustic analysis. The force balance method examines whether the valve can remain open throughout its lift range. It compares the upward force from inlet pressure (after losses) plus any assist from the huddling chamber against the downward forces from spring preload, backpressure, and fluid drag. If positive margin exists across all operating points, the valve should remain stable.

Solutions When Inlet Loss Exceeds 3%

When calculations show that inlet pressure drop exceeds 3%, and engineering analysis cannot justify the excess, engineers have several options to bring the system into compliance. Each approach has different costs, implementation challenges, and effects on overall system performance.

The most direct solution is modifying the inlet piping itself. Increasing the pipe diameter dramatically reduces pressure loss because friction drop is inversely proportional to the fifth power of diameter. Upgrading from a 2-inch to a 3-inch inlet line can reduce pressure loss by a factor of seven or more. However, this requires replacing piping, possibly modifying the vessel nozzle, and dealing with hot work permits and plant shutdowns.

Modifying the entrance geometry offers a low-cost option for marginal cases. Replacing a sharp-edged nozzle connection with a rounded entrance can recover 1% to 2% of set pressure at minimal expense. This simple change involves machining work that can often be done during a planned maintenance window without extensive piping modifications.

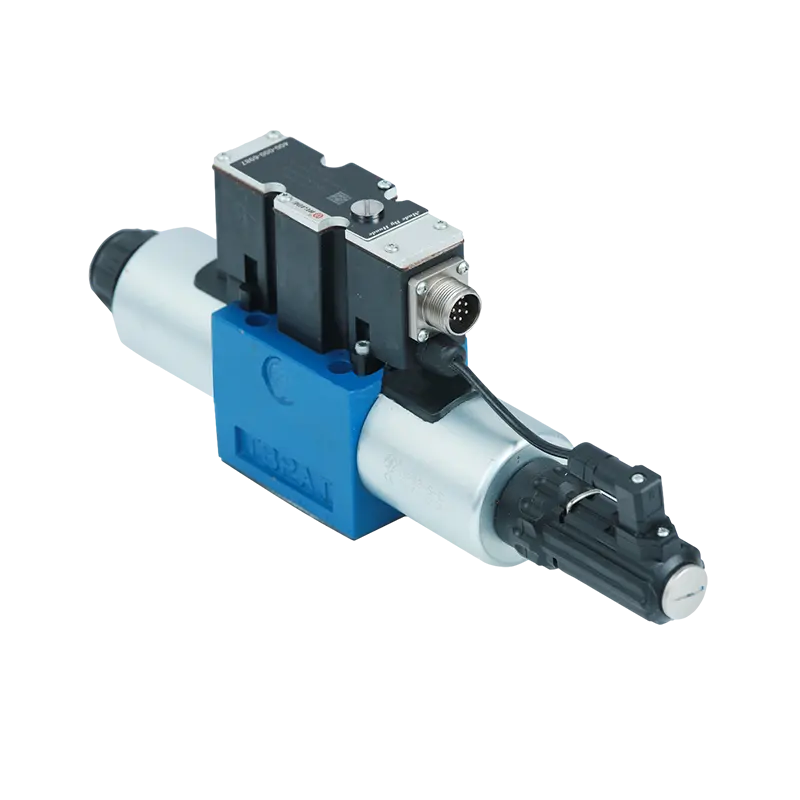

Pilot-operated relief valves (PORV) offer a fundamentally different solution. Unlike conventional valves where the process fluid directly acts on the disc, pilot-operated valves use a small pilot valve to control a larger main valve. The pilot can sense pressure through a remote sensing line connected directly to the protected vessel. This arrangement completely bypasses the inlet piping pressure loss problem because the sensing point is upstream of any inlet losses. API 520 explicitly exempts pilot-operated valves with remote sensing from the 3% inlet loss limitation.

| Solution | Effectiveness | Typical Cost | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase pipe diameter | Very High (ΔP ∝ 1/D⁵) | $15,000-$50,000 | High - requires hot work, shutdown |

| Shorten inlet length | High - reduces friction and acoustic lag | $10,000-$40,000 | High - limited by layout constraints |

| Rounded entrance | Moderate (saves 1-2% typically) | $1,000-$5,000 | Low - machining work only |

| Restrict valve lift | High (ΔP ∝ Q²) | $2,000-$8,000 | Moderate - must verify capacity |

| Increase blowdown | Moderate - increases margin | $1,000-$3,000 | Low - adjustment only |

| Pilot-operated valve (PORV) | Complete solution | $20,000-$60,000 | Moderate - temperature limited |

Real-World Consequences of Ignoring the Rule

The 3% rule exists because violations have caused serious accidents in industrial facilities. Understanding these incidents helps explain why regulatory agencies and insurance companies take the rule seriously.

During an upset in the hydroprocessing unit, a relief valve entered violent chatter mode due to inadequate inlet piping. Within minutes, the high-frequency vibration fatigued the bolting at the valve flanges. Large quantities of flammable naphtha sprayed from the gaps and ignited, killing two operators. The CSB investigation linked the failure directly to instability caused by inlet pressure loss.

During a pop test at 1,650 psig, a valve began chattering violently. The dynamic forces caused the entire valve assembly to shear from its test fixture. The 4.42-pound valve became a projectile that penetrated the ceiling before falling and causing severe injury to a technician.

A propylene distillation column overpressured and the relief valve activated. Chatter caused flange leakage, releasing propylene that found an ignition source. The resulting explosion caused extensive damage and shut down the facility for months.

Regulatory and Legal Aspects

In the United States, compliance with the 3% rule carries legal weight beyond simple engineering best practice. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Process Safety Management (PSM) regulation at 29 CFR 1910.119 requires that equipment comply with Recognized and Generally Accepted Good Engineering Practices (RAGAGEP). OSHA explicitly recognizes API 520 and ASME Section VIII as RAGAGEP for pressure relief systems.

This means that a relief valve installation that violates the 3% rule without documented engineering justification is considered a direct violation of federal safety regulations. During OSHA PSM inspections and National Emphasis Program (NEP) audits, inspectors routinely request relief valve calculation packages. If these calculations show inlet losses exceeding 3% without proper engineering analysis documentation, the facility faces citations that can include substantial penalties.

Best Practices for Compliance

Engineers can avoid 3% rule problems through proper practices in design, installation, and ongoing management. Following these approaches reduces both safety risk and regulatory exposure.

During initial design, locate relief valves as close as practically possible to protected equipment. Select inlet pipe size using rigorous hydraulic calculations rather than rules of thumb. A common error is assuming the inlet line can be the same size as the relief valve inlet connection; for valves 3 inches and larger, the inlet piping often needs to be at least one pipe size larger than the valve connection.

Document all assumptions and calculations in the relief valve design package. If engineering analysis is performed to justify exceeding 3%, this analysis must be documented in detail with all supporting calculations. Implement a management of change procedure that specifically flags relief system impacts—common changes like production rate increases can significantly alter inlet pressure loss.

Practical Calculation Example

Consider a practical example to illustrate the calculation process. A horizontal pressure vessel operating at 150 psig requires overpressure protection. The relief valve is set at 165 psig. The valve selected has an orifice area of 1.838 square inches and a rated capacity of 54,300 lb/hr for saturated steam.

The inlet piping consists of 10 feet of 3-inch Schedule 40 pipe with two 90-degree elbows and a flush square-edged entrance. We need to verify that inlet pressure loss remains below 3% of set pressure (4.95 psig).

Using the Darcy-Weisbach method, we calculate steam density and velocity (approx 203 ft/s). The Reynolds number indicates turbulent flow, giving a friction factor of 0.015. The straight pipe friction loss is approx 1.2 psi. Two elbows add 1.8 psi. The entrance loss is 1.1 psi.

Total inlet pressure loss = 4.1 psig. Comparing this to the allowable 4.95 psig shows the design meets the 3% rule with about 17% margin.

Conclusion

The 3% rule for pressure relief valve inlet pressure loss represents decades of engineering experience distilled into a practical design criterion. While it may seem like an arbitrary threshold, it directly addresses the real physical phenomenon of valve instability and chatter that has caused fatalities and major equipment damage in industrial facilities.

Understanding the rule requires appreciating both its purpose and its limitations. The 3% limit provides a conservative screening criterion that works for most conventional spring-loaded valves in typical applications. Compliance involves proper initial design, careful calculation of all pressure loss components using rated valve capacity, attention to details like entrance geometry, and thorough documentation.