Pressure reducing valves are critical components in fluid systems that control downstream pressure regardless of upstream fluctuations. Whether you're dealing with a residential water system running at 80 psi from the municipal main or an industrial hydraulic circuit requiring precise pressure control for different actuators, knowing how to adjust pressure reducing valves correctly can prevent equipment damage, reduce energy waste, and ensure system safety.

The adjustment process is not simply about turning a screw. It involves understanding the force balance principle that governs valve operation, recognizing the differences between direct-acting and pilot-operated designs, and following specific procedures based on the medium being controlled—water, hydraulic oil, steam, or compressed air. This guide draws from field-tested procedures across multiple industries to provide you with actionable knowledge for adjusting pressure reducing valves in various applications.

Understanding Pressure Reducing Valves Before Adjustment

The Force Balance Principle

Before you attempt to adjust any pressure reducing valve, you need to understand what's happening inside the valve body. Every pressure reducing valve operates on a force balance principle. Three main forces interact to determine the outlet pressure: the loading force (typically from a calibrated spring), the sensing force (created by downstream pressure acting on a diaphragm or piston), and various friction forces from seals and flow dynamics.

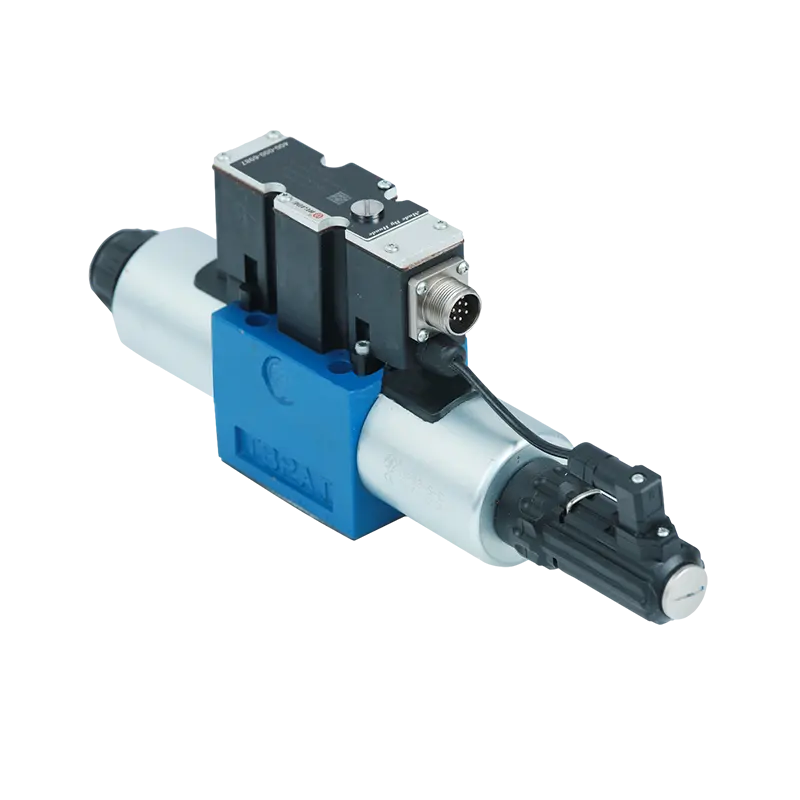

When you adjust a pressure reducing valve, you're changing the loading force by compressing or releasing the main spring. This breaks the existing force equilibrium and forces the valve spool to find a new balance position. In a direct-acting pressure reducing valve, the adjustment screw directly compresses the main spring. These valves respond extremely fast but exhibit significant pressure droop characteristics—meaning outlet pressure decreases noticeably as flow increases.

Pilot-operated pressure reducing valves work differently. Your adjustment affects a small pilot valve that amplifies the signal by controlling hydraulic or pneumatic pressure in the main valve chamber. This design provides superior control accuracy and a flat flow-pressure curve, but it introduces more complex dynamic response characteristics and potential lag. The key difference matters because adjusting a pilot-operated steam valve is essentially tuning a negative feedback control loop gain, while adjusting a home water pressure reducing valve is setting a direct mechanical balance point.

You also need to distinguish between reducing valves and relief valves, especially in hydraulic systems. Relief valves are normally closed and open only when pressure exceeds the setpoint to dump fluid back to the tank. They're installed in parallel with the pump. Pressure reducing valves are normally open and installed in series within a branch circuit to maintain a lower pressure than the main system. Confusing these two can lead to pump overload or actuator control failure.

Tools and Measurement Requirements

Accurate adjustment of any pressure reducing valve starts with proper measurement tools. You cannot rely on guesswork or system behavior alone. For water systems, you need a standard water pressure gauge with hose thread connections, typically reading 0-100 psi or 0-160 psi. The gauge should have a soft seal for outdoor faucet connections.

In hydraulic systems, pressure measurement becomes more critical. You must install the gauge downstream of the pressure reducing valve—on the reduced pressure side—not on the main system side. Many technicians make the mistake of reading main system pressure and wondering why their adjustments have no effect. The gauge should have appropriate pressure range (typically 0-5000 psi for industrial hydraulics) and be installed with isolation valves for safety.

Steam systems require special attention to gauge installation. The sensing line that connects the pilot valve to the downstream pressure point must be properly sloped away from the valve body. This prevents condensate from accumulating in the pilot diaphragm chamber, which would create a water seal and cause severe pressure hunting or oscillation. The slope should be continuous with no low points where water can pool.

| System Type | Primary Tools | Measurement Equipment | Special Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential Water | Adjustable wrench, flathead screwdriver | 0-100 psi water pressure gauge with hose connection | Outdoor faucet access for testing |

| Industrial Hydraulic | Allen keys, torque wrench | 0-5000 psi hydraulic gauge with isolation valve | Lockout/tagout procedures, oil temperature monitoring |

| Steam System | Pipe wrenches, sensing line tools | 0-300 psi steam gauge, thermometer | Warm-up valve, condensate drain capability |

| Pneumatic | Screwdriver or hex key | 0-150 psi air pressure gauge | Vent port access (for relieving type) |

For all systems, you also need basic hand tools to loosen and tighten the locknut that secures the adjustment mechanism. This locknut prevents vibration from changing your settings over time. Always use the correct size wrench to avoid rounding off the hex faces.

How to Adjust Water Pressure Reducing Valves in Residential Systems

Residential water pressure reducing valves are almost always spring-loaded direct-acting diaphragm designs. They're installed on the main water line after the shutoff valve and often include integrated check valve functions. The standard factory setting is typically 50 psi, which balances shower flow comfort against equipment protection. However, you may need to adjust this based on local conditions or specific requirements.

The adjustment process follows a specific sequence that many homeowners miss, leading to frustration when pressure doesn't change as expected. Start by establishing your baseline pressure. Connect your water pressure gauge to an outdoor faucet downstream of the pressure reducing valve. Close all indoor faucets, showers, and water-using appliances like washing machines and dishwashers. The reading you get now is your static pressure. If this static pressure exceeds 80 psi, you must reduce it immediately to protect your plumbing fixtures and prevent premature pipe failure.

Next, perform a dynamic test by opening one faucet and watching the pressure gauge. If pressure drops from 60 psi to 20 psi, this indicates the valve may have a clogged strainer or be undersized for your flow requirements. No amount of adjustment will fix this—you need maintenance or replacement.

The Adjustment Procedure

Once you've confirmed the valve is functioning, locate the adjustment mechanism on top of the valve body. You'll see an adjustment bolt or screw held in place by a locknut. Use your adjustable wrench to turn the locknut counterclockwise until it completely disengages from the adjustment bolt threads. Don't force it if it's corroded—apply penetrating oil and wait.

Now comes the actual adjustment. The core principle is simple: clockwise rotation increases pressure, counterclockwise rotation decreases pressure. This logic comes from the screw thread principle—turning clockwise pushes down on the spring, increasing the force the diaphragm must overcome.

Make your adjustments in small increments. Turn the adjustment bolt only one-quarter to one full turn at a time. Large pressure jumps can stress weak points in your piping or damage the diaphragm inside the valve. After each adjustment, you must perform a critical step that many people skip: pressure relief and stabilization.

When you turn the adjustment bolt counterclockwise to reduce pressure, the gauge reading won't drop immediately. This happens because your downstream piping is a closed system with trapped high-pressure water. To see the new setting, open a downstream faucet and let water flow for 15-30 seconds, then close it. This not only releases the trapped high-pressure water but also cycles the valve through an open-close sequence, allowing internal components to reposition under the new spring tension.

Wait a moment after closing the faucet, then read the gauge again. Repeat this adjust-drain-read cycle until you reach your target pressure. Most experts recommend setting residential systems between 55-60 psi for optimal performance and equipment longevity.

After achieving your target pressure, secure the setting by holding the adjustment bolt steady with one hand while tightening the locknut clockwise with your other hand until it seats firmly against the valve body. Check the gauge one final time to confirm the pressure didn't shift during locknut tightening.

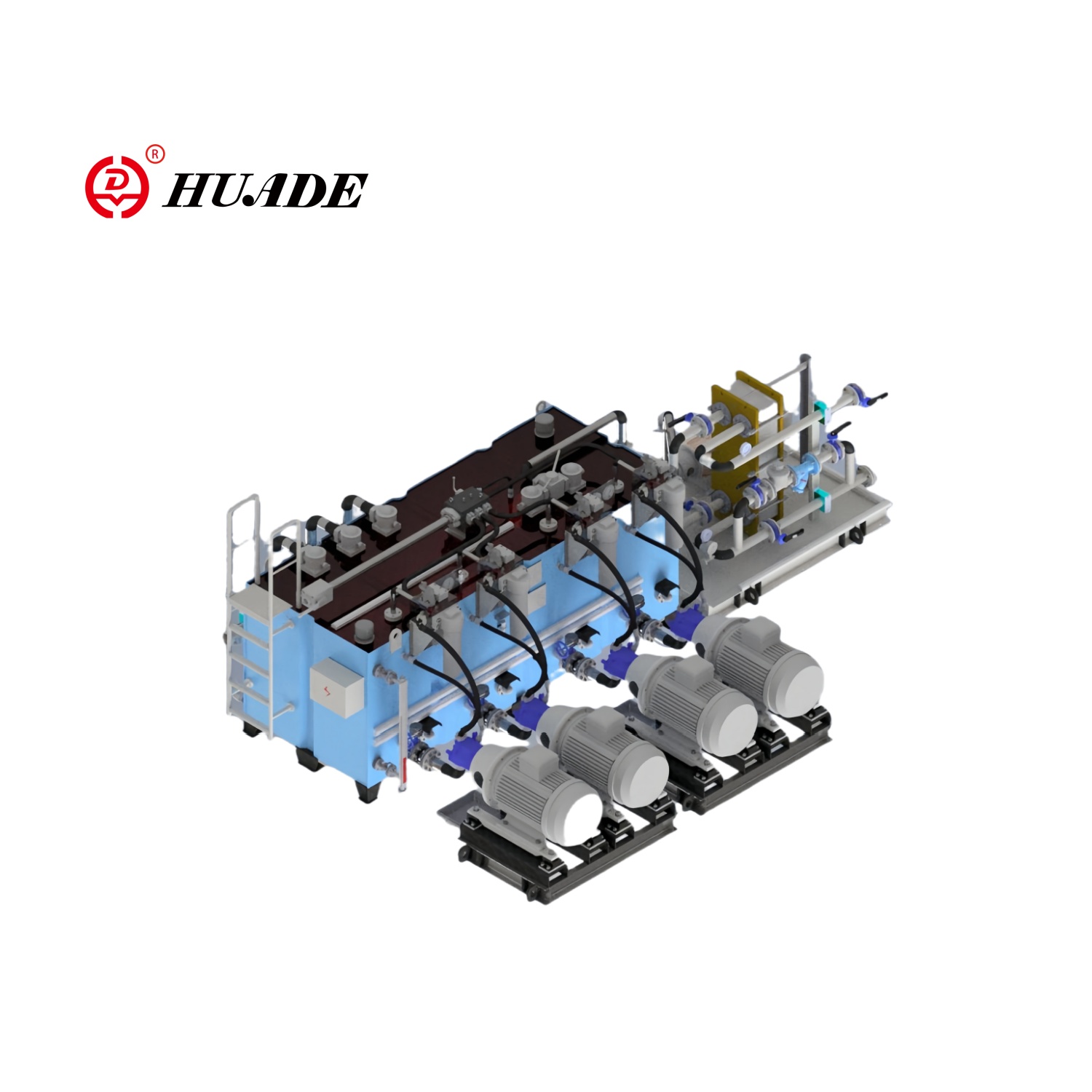

Adjusting Pressure Reducing Valves in Industrial Hydraulic Systems

Hydraulic pressure reducing valves require much more rigorous adjustment procedures than water valves, especially in cartridge or stack valve configurations. The adjustment involves creating a deadhead condition and understanding the interaction between main system pressure and branch circuit pressure.

Before starting any adjustment, verify you're working with a reducing valve and not a relief valve. This distinction is critical in hydraulic systems. Relief valves are installed in parallel with the pump and limit maximum system pressure. Reducing valves are in series with a branch circuit and maintain constant lower pressure in that branch regardless of main system pressure fluctuations.

Gauge location is absolutely critical. You must install your pressure gauge downstream of the pressure reducing valve on the reduced pressure circuit. If you measure upstream or on the main system, you'll only see main system pressure and your adjustments will appear to have no effect. Many troubleshooting hours have been wasted because technicians measured at the wrong location.

Bring the system to normal operating temperature before fine adjustment. Hydraulic oil viscosity changes significantly with temperature, affecting the drag on the valve spool. A setting made at 20°C will behave differently when the oil reaches 50°C. Run the system through several cycles until oil temperature stabilizes, typically between 40°C and 50°C.

Creating a Deadhead Condition

To accurately set the opening pressure, you need to create a deadhead condition in the branch circuit. This means blocking flow so the circuit has zero flow and only static pressure. For example, run a cylinder to its end of stroke and hold it there. This eliminates flow-induced pressure drop and allows you to set the valve's closing point precisely.

Loosen the locknut on the adjustment mechanism. The adjustment logic follows the same clockwise-to-increase principle as water valves. Turning the adjustment screw clockwise compresses the spring, increasing the resistance to valve spool opening, which raises the outlet pressure setpoint. Turning counterclockwise releases spring tension and lowers the pressure setpoint.

One critical prerequisite: main system pressure must be higher than your desired reduced pressure setting. If your main system runs at 100 bar, you cannot adjust a reducing valve to 150 bar. The reducing valve can only reduce pressure, not create it.

Modern high-performance hydraulic reducing valves often have reducing/relieving capability. These are three-port valves that not only reduce incoming pressure but also relieve downstream pressure if it rises above the setpoint due to external forces, like a load falling on a cylinder. When adjusting these valves, verify both functions: pressure reduction during normal operation and pressure relief when the downstream circuit is pressurized from an external source.

Pay special attention to the external drain line. All pilot-operated hydraulic reducing valves require a separate drain line back to the tank. This drain line provides the reference pressure for the pilot spring chamber. If this line has backpressure from being combined with other return lines or from flow restrictions, that backpressure adds directly to your setpoint on a 1:1 ratio. For example, if you set 50 bar but the drain line has 10 bar of backpressure, actual outlet pressure will be 60 bar. Checking drain line integrity is the first step when you cannot adjust pressure down to the desired level.

| Symptom | Physical Cause | Diagnostic Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure instability with gauge needle oscillation | Air trapped in pilot oil passages; worn valve seat creating turbulent flow | Listen for buzzing sound; check for milky appearance in sight glass | System purge by repeated load/unload cycles; replace spool assembly |

| Pressure drift upward during operation | Pilot damping orifice partially clogged with oil varnish | Monitor pressure rise rate over 10-15 minutes of operation | Disassemble and clean damping orifice; replace main filter element |

| Cannot reduce pressure below main system pressure | External drain port (Y-port) blocked or has excessive backpressure | Install gauge on drain line; should read less than 5 bar | Clear drain line obstruction; separate from high-flow return lines |

| Outlet pressure equals inlet pressure | Main valve spool stuck in full-open position; pilot valve contaminated | Check pilot adjustment; listen for pilot valve operation sound | Flush pilot circuit; clean or replace main spool; verify filtration meets ISO 4406 16/14/11 |

Adjusting Steam System Pressure Reducing Valves

Steam pressure reducing valves present unique challenges because steam is a compressible, high-energy medium that can condense into water slugs if handled improperly. The adjustment procedure must include rigorous warm-up and condensate removal protocols to prevent water hammer damage or valve destruction.

Industrial steam systems typically use pilot-operated pressure reducing valves to maintain stable outlet pressure despite large flow variations. The pilot valve creates a control pressure that acts on the main valve's large diaphragm or piston to modulate the main valve opening. Your adjustment on the pilot valve spring sets the control pressure, which the negative feedback loop maintains.

Warm-up Sequence

Before making any adjustments, you must perform the warm-up sequence. Never open a reducing valve suddenly into cold piping. The temperature differential causes rapid steam condensation, creating high-velocity water slugs that can shatter cast iron valve bodies or rupture bellows. Start by draining all condensate from inlet piping through the steam separator and steam trap. This is the first rule of preventing water hammer.

For large reducing stations with 3-inch (DN80) or larger main valves, use the warm-up bypass valve. This small parallel valve allows you to send a small amount of steam downstream gradually. The purpose is to slowly heat the downstream piping and build up backpressure before opening the main valve. This balances the pressure differential across the main isolation valve, preventing seal surface wire-drawing from high-differential pressure operation.

To adjust the pilot valve, start with downstream isolation valves closed or slightly open. Completely release the pilot adjustment screw by turning it fully counterclockwise, removing all spring force. Slowly open the upstream inlet stop valve. Now begin turning the pilot adjustment screw clockwise slowly. You should hear steam flow as the pilot begins to open.

Watch your downstream pressure gauge, but understand there will be thermal lag. Steam systems take time to reach thermal equilibrium. Make small adjustments and wait several minutes between changes to let the system stabilize. When you reach your setpoint, fully open the downstream isolation valve and fine-tune based on actual load conditions.

The sensing line configuration is critical to stable operation. This external pipe connects the pilot valve to a pressure tap point downstream of the main valve. The sensing point must be at least 10 pipe diameters downstream and away from elbows or fittings to capture stable laminar flow static pressure rather than turbulent pressure. The sensing line must slope downward away from the valve body. This gravity drainage prevents condensate from accumulating in the pilot diaphragm chamber. If water fills this chamber, it creates a liquid seal that severely delays pressure signal transmission, causing the valve to hunt or oscillate between fully open and closed positions.

Troubleshooting Common Adjustment Issues

Even with correct procedures, you may encounter situations where pressure reducing valve adjustment doesn't produce expected results. Understanding these failure modes helps you distinguish between adjustment problems and component failures requiring maintenance or replacement.

Regulator creep is one of the most common issues in water systems. This refers to downstream pressure slowly rising toward inlet pressure when no water is being used. The cause is always valve seat leakage—the disc isn't sealing properly against the seat due to debris, cavitation damage, or seal wear. To diagnose creep, close all water outlets to create a sealed system. Watch your pressure gauge for 15-30 minutes. If pressure remains constant, the valve seals properly. If the gauge needle climbs steadily, you have confirmed creep.

Distinguish creep from thermal expansion effects. If pressure rise only occurs during water heater heating cycles and drops quickly when you open a faucet briefly, that's thermal expansion of heated water in a closed system, not valve failure. The solution is installing a thermal expansion tank, not adjusting the pressure reducing valve.

Noise and vibration during water flow often indicates hydrodynamic instability. This buzzing or chattering sound comes from excessive flow velocity through an undersized valve, loose locknut allowing spring resonance, or worn valve disc seal. Try micro-adjusting pressure slightly higher, which sometimes changes the spring's natural frequency and eliminates resonance. If this fails, you need to disassemble for cleaning or component replacement.

In hydraulic systems, pressure instability shows as rapid gauge needle oscillation with possible buzzing sounds. This typically means air trapped in pilot oil passages or a worn valve seat creating turbulent flow. The correction involves repeated system purging through load/unload cycles or replacing the spool assembly. If you see milky appearance in the sight glass, air contamination is confirmed.

Pressure drift—where pressure slowly rises during operation—usually indicates the pilot damping orifice is partially clogged with oil varnish or decomposition products. This restricts the flow that provides damping in the pilot circuit, making the valve respond too aggressively. Disassembly and careful cleaning of this tiny orifice, combined with replacing the main system filter element, usually resolves the issue.

When you cannot adjust pressure below main system levels in a hydraulic system, immediately check the external drain line. This is the most overlooked diagnostic step. Install a gauge on the drain line—it should read less than 5 bar. If you see higher backpressure, find and clear the obstruction or separate the drain from high-flow return lines.

For pneumatic systems, understanding whether you have a relieving or non-relieving regulator is critical to troubleshooting. Relieving regulators have a vent port that opens to exhaust excess downstream pressure when you turn the adjustment counterclockwise. You'll hear a distinct hissing sound as air escapes, and the gauge will drop immediately. Non-relieving regulators cannot exhaust air automatically. When you turn the adjustment counterclockwise in a deadhead condition, the gauge won't change because trapped air has nowhere to go. You must manually vent downstream through a bleed valve to see the new setting.

Supply pressure effect in pneumatic regulators is a counterintuitive phenomenon. When inlet pressure drops—like a gas cylinder running low—outlet pressure actually rises. This happens because inlet pressure acts on the bottom of the valve poppet, creating an upward closing force. When this force decreases, the top-side balancing spring pushes the poppet more open, increasing outlet pressure. For systems supplied by high-pressure cylinders, you need to monitor source pressure and readjust the regulator periodically as the cylinder depletes.

Maintenance and Preventive Measures

The best adjustment technique cannot compensate for a valve in poor physical condition. Establishing preventive maintenance routines is the foundation for stable pressure control. Most pressure reducing valve failures originate from contamination. Clean the strainer or Y-type filter quarterly at minimum. For steam systems, a clogged strainer causes severe steam starvation and sudden pressure drops that can damage downstream equipment.

Diaphragms are wear components with finite service life. Rubber diaphragms harden and crack over time, especially in high-temperature applications. For critical systems, plan preventive replacement every three to five years before failure occurs. A leaking pilot valve bonnet cap is the most obvious sign of diaphragm rupture.

Valve seat condition determines sealing quality. Long-term exposure to high-velocity fluid erosion creates microscopic grooves called wire-drawing on the seat surface. During annual overhauls, inspect the seat sealing surface finish. If you feel roughness with your fingernail or see visible scoring, the seat ring requires lapping or replacement.

Hysteresis testing helps identify friction problems. Set the valve to 50 psi by adjusting upward from 40 psi. Record the actual pressure. Then adjust downward from 60 psi to the same 50 psi setting. If the actual pressures differ significantly between these two approaches, you have excessive friction from O-ring seals or stem guides. The mitigation strategy is always to approach your target setpoint from below. If you need to decrease pressure, first turn the adjustment well below your target (like 40 psi), vent or drain the system, then turn back up clockwise to your target (50 psi). This ensures the spring always loads from the same side, eliminating mechanical deadband.

Understanding when to adjust versus when to replace saves time and prevents recurring problems. If you need to adjust a valve more than twice per year, investigate the root cause—changing system demands, component wear, or contamination issues. If adjustment range is exhausted (screw at maximum extension or compression), the spring has likely weakened from fatigue or the valve is severely oversized or undersized for actual conditions. These situations require valve replacement, not continued adjustment attempts.

Documentation

Proper documentation of all adjustments, including date, pressure readings before and after, adjustment direction and amount, and any observed anomalies creates a valuable historical record. This data helps predict maintenance needs and identify slowly developing problems like gradual spring weakening or progressive seat wear.

Adjusting pressure reducing valves successfully requires combining mechanical procedure with fluid system knowledge. The core operations—turning clockwise to increase pressure and counterclockwise to decrease—remain consistent, but the surrounding protocols vary dramatically based on the medium being controlled. Water systems need pressure relief steps to overcome static lockup. Hydraulic systems demand deadhead conditions and careful drain line verification. Steam systems require rigorous warm-up sequences and sensing line configuration. Pneumatic systems need understanding of relieving versus non-relieving characteristics. Master these fundamentals, apply them systematically, and you'll achieve stable, reliable pressure control across any system you encounter.