When we talk about protecting hydraulic systems from dangerous pressure surges, the hydraulic pressure relief valve stands as the most critical safety component. This valve serves a dual purpose in fluid power systems: it acts as a pressure regulator during normal operation and becomes a safety guardian when system pressure threatens to exceed safe limits. Understanding how these valves work, their different types, and how to select the right one can make the difference between a reliable system and costly equipment failure.

What is a Hydraulic Pressure Relief Valve and How Does It Work

A hydraulic pressure relief valve operates on a simple yet elegant force balance principle. At its core, the valve contains a moving element called the poppet or spool that sits against a valve seat. This element is held closed by a spring with a specific stiffness coefficient (k). On the opposite side, hydraulic fluid pressure pushes against the effective area of the poppet.

The physics follows Pascal's Law and Hooke's Law. The hydraulic force can be expressed as F_h = P × A, where P represents the inlet pressure and A is the effective pressure area of the poppet. The spring force opposing this is F_s = k × (x₀ + x), where x₀ is the spring preload compression and x is the additional displacement after opening.

When system pressure remains below the setpoint, the spring force keeps the valve firmly closed. All flow continues to the actuators and cylinders. But when pressure rises due to external loads or pump overrun, the hydraulic force eventually overcomes the spring force. The poppet lifts off its seat, creating a flow restriction. Fluid begins routing back to the tank, preventing further pressure increase.

This process involves significant energy conversion. High-pressure fluid passing through the valve orifice experiences a rapid pressure drop. The pressure energy converts first to kinetic energy, then dissipates as heat through turbulent flow. This is why relief valves can generate considerable heat during prolonged relief cycles, sometimes requiring external cooling or oversized reservoirs to maintain acceptable oil temperatures.

The valve accomplishes three distinct functions depending on its circuit position. As a safety relief valve, it sits as the last line of defense with a setpoint typically 10-20% above maximum working pressure. In pressure regulating mode, particularly with fixed displacement pumps, the hydraulic pressure relief valve maintains constant system pressure by continuously diverting excess pump flow. For unloading circuits, especially in pilot-operated designs, the valve can drop system pressure to near-zero for energy savings during idle periods.

Types of Hydraulic Pressure Relief Valves: Direct-Acting vs Pilot-Operated

The hydraulic pressure relief valve family splits into two fundamental architectures, each with distinct performance characteristics that determine their ideal applications.

Direct-Acting Relief Valves

Direct-acting valves represent the simplest and most robust design. Hydraulic oil acts directly on the main poppet face, pushing directly against the adjustment spring. No intermediate control chambers or pilot stages exist. This straightforward design gives direct-acting valves their most valuable characteristic: extremely fast response time.

When a pressure spike hits the system, direct-acting valves can open in under 10 milliseconds, with some high-performance designs responding in as little as 2 milliseconds. This makes them ideal for absorbing pressure transients like water hammer effects or sudden load changes. In mobile equipment with variable loads or in circuits protecting cylinders during deceleration, direct-acting valves excel at clipping pressure peaks before they damage seals or burst hoses.

However, this simple design carries a significant limitation called pressure override. As flow through the valve increases, the poppet must compress the spring further to enlarge the orifice area. According to Hooke's Law, greater spring compression requires proportionally higher force, which means higher inlet pressure. Additionally, high-velocity fluid flowing past the poppet creates steady-state flow forces that tend to close the valve, requiring even more pressure to maintain the opening.

The result is a steep pressure-flow characteristic curve. The full-flow pressure (pressure needed to pass maximum rated flow) can exceed the cracking pressure (initial opening pressure) by 30% or even 50% in some designs. For precision control systems where pressure stability matters, this flow-dependent pressure rise is unacceptable.

Pilot-Operated Relief Valves

Pilot-operated designs solve the pressure override problem through a two-stage control architecture. The valve consists of a small direct-acting pilot stage that sets the pressure limit, and a larger main stage that handles the bulk flow. The main stage poppet has a small orifice drilled through it, allowing system pressure to equalize on both sides of the poppet in the closed position.

The top chamber of the main poppet connects to the pilot valve outlet. When system pressure stays below setpoint, the pilot valve remains closed, maintaining equal pressure above and below the main poppet. A light spring combined with slightly larger top surface area keeps the main poppet sealed on its seat.

When pressure exceeds the pilot setpoint, the pilot poppet opens, allowing a small amount of oil to flow to tank. This creates a pressure drop across the main poppet's internal orifice. The differential pressure overcomes the weak main spring, pushing the main poppet open to relieve the primary flow path.

The beauty of this design lies in its minimal pressure override. Since the main poppet opens primarily through hydraulic differential pressure rather than spring compression, and because the main spring is very soft, only a tiny pressure increase is needed to move from cracking pressure to full flow. Typical pilot-operated hydraulic pressure relief valves achieve pressure override of just 50-100 PSI, or under 5% of setpoint, regardless of flow rate. This creates an extremely flat pressure-flow characteristic curve.

The tradeoff comes in response time. Pressure signals must first trigger the pilot valve, establish pilot flow, create pressure drop across the damping orifice, and finally move the larger mass of the main poppet. This sequence typically requires around 100 milliseconds, roughly ten times slower than direct-acting designs. For steady-state pressure regulation this delay rarely matters, but for fast transient protection, pilot-operated valves may not react quickly enough to prevent brief pressure spikes.

| Performance Characteristic | Direct-Acting | Pilot-Operated |

|---|---|---|

| Response Time | Very fast (<10 ms) | Slower (~100 ms) |

| Pressure Override | High (30%+ possible) | Low (<5-10%) |

| Flow Capacity | Limited by spring size | High capacity in compact size |

| Pressure Stability | Varies significantly with flow | Flat pressure-flow curve |

| Contamination Sensitivity | Low (no small orifices) | Higher (pilot orifice can clog) |

| Hysteresis | Moderate to high | Low (1-3%) |

| Typical Applications | Transient protection, brake circuits, small flow systems | Main system relief, large pump stations, steady-state control |

Key Performance Parameters You Need to Know

When selecting a hydraulic pressure relief valve, the nameplate pressure rating tells only part of the story. Several critical parameters define how the valve will actually behave in your system.

Cracking Pressure vs Full Flow Pressure

Cracking pressure refers to the inlet pressure at which the valve first begins passing a small amount of fluid. ISO standards typically define this as the pressure at which flow reaches a specific low rate, often 1 liter per minute or a certain number of drops per minute. This distinction matters because if you set cracking pressure equal to your maximum system pressure, the valve may start weeping before you reach that pressure, causing efficiency losses and heat generation.

Full flow pressure is the inlet pressure required to pass the valve's maximum rated flow. For direct-acting valves, this can be substantially higher than cracking pressure due to spring compression requirements. For pilot-operated designs, these two values remain very close.

Hysteresis and Control Uncertainty

Hysteresis represents the pressure difference between the rising pressure at which the valve opens and the falling pressure at which it closes, measured at the same flow point. This phenomenon results from mechanical friction in seals and poppet guides, plus magnetic hysteresis in proportional solenoids if present. High hysteresis, say above 10%, creates control uncertainty. Modern pilot-operated valves achieve hysteresis as low as 1-3%, making them suitable for closed-loop control systems.

Reseat Pressure and System Efficiency

Reseat pressure is the pressure at which the valve fully closes and stops significant flow after a relief cycle. This value always falls below cracking pressure. A low reseat ratio, such as 80% of cracking pressure, means the system loses substantial pressure after each actuation. Actuators may respond slowly or feel weak. Quality valves maintain reseat pressure above 90% of cracking pressure to preserve system efficiency.

Flow Coefficient and Sizing

Every hydraulic pressure relief valve has a rated flow capacity at a specific pressure drop. Undersizing leads to excessive pressure override or inability to protect the system. Oversizing in direct-acting valves can cause instability at low flows, leading to chattering or squealing noise. The valve should be sized so that maximum system flow occurs within the stable operating region of the valve's characteristic curve.

Advanced Applications and Circuit Functions

Modern hydraulic circuits use the hydraulic pressure relief valve for far more than simple overpressure protection. Engineers exploit their unique characteristics to implement sophisticated system logic.

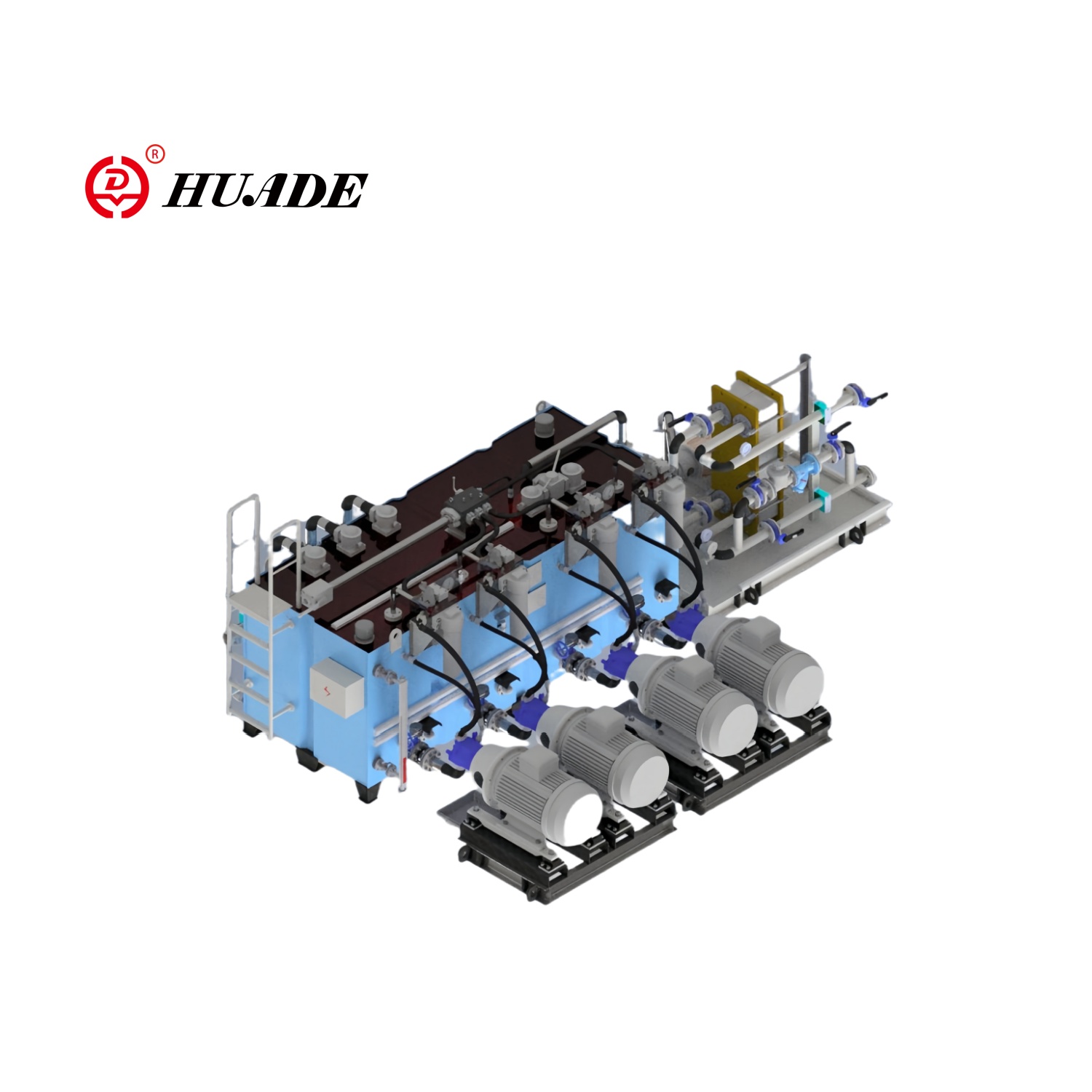

Remote Unloading and Multi-Pressure Circuits

Pilot-operated relief valves include a vent port, typically marked as the X port, which connects directly to the main poppet's upper chamber. By connecting this port to tank through a solenoid valve, you can instantly unload the system. With the upper chamber vented, the main poppet needs to overcome only the weak main spring, typically requiring just 50-100 PSI. The pump output flows freely to tank at near-zero pressure, dramatically reducing power consumption and heat generation during idle periods.

This principle extends to multi-pressure control. By connecting the X port to a series of smaller direct-acting relief valves through selector valves, a single main valve can provide different pressure limits for different machine operations. A hydraulic press might use low pressure for rapid approach, switch to high pressure for forming, and use medium pressure for return stroke. This costs far less than proportional valves while maintaining reliability.

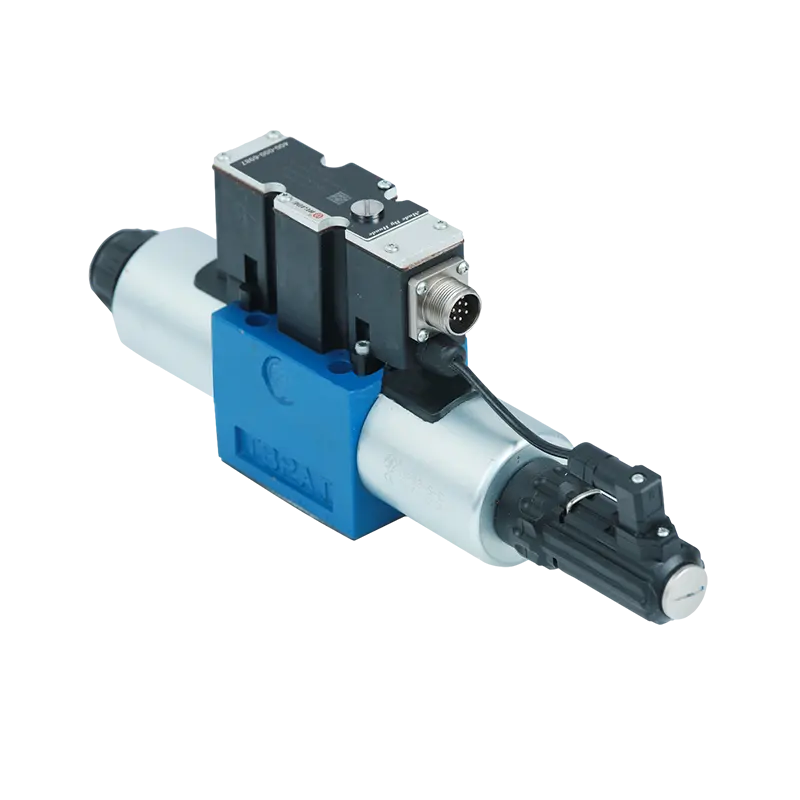

Proportional Pressure Control

Replacing the manual adjustment knob with a proportional solenoid creates an electronically controlled hydraulic pressure relief valve. Most proportional solenoids use pulse-width modulation (PWM) rather than pure DC voltage. The high-frequency dither introduced by PWM reduces static friction in the valve poppet, lowering hysteresis and improving repeatability.

Quality amplifiers employ current feedback control rather than voltage control. As the solenoid coil heats during operation, its resistance increases. Voltage control would reduce current and magnetic force, causing pressure drift. Current control maintains constant force regardless of temperature, stabilizing pressure output. Some designs use inverse proportional characteristics where maximum pressure occurs at zero current, providing fail-safe operation if electrical power is lost.

Thermal Relief Valves

In circuits where actuators or volumes of fluid can become isolated and trapped, temperature changes pose a serious threat. Aircraft parking brakes and locked hydraulic cylinders face this issue. As ambient temperature rises, the trapped fluid expands. Since hydraulic oil has low compressibility, even slight thermal expansion in a sealed volume generates enormous pressure that can burst lines or seals.

Miniature thermal relief valves, often called thermal expansion valves, solve this problem. These specialized hydraulic pressure relief valves have very small flow capacity but extremely low leakage. They remain sealed during normal operation but relieve the tiny volume of fluid needed to compensate for thermal expansion, preventing catastrophic failures.

Common Problems and Troubleshooting

Despite their apparent simplicity, hydraulic pressure relief valves can exhibit complex failure modes that challenge even experienced technicians. Understanding the underlying physics helps diagnose issues faster.

Chatter and Squeal: Instability Phenomena

Chatter manifests as a low-frequency, high-amplitude pounding sound as the poppet violently impacts the valve seat. This usually indicates the valve is oversized for the application. With very low flow rates, the poppet operates near its opening point where the system becomes dynamically unstable. Small pressure fluctuations cause the poppet to repeatedly slam shut and reopen. Long inlet lines can worsen this by creating pressure wave reflections that resonate with the poppet's natural frequency.

Squeal produces a high-pitched, piercing noise resulting from resonance in the pilot chamber or fluid shear layer instability. Air entrainment, where microscopic bubbles enter the oil, commonly triggers squealing. The bubbles act as tiny springs, changing the fluid's effective bulk modulus and shifting system resonance frequencies. Entrained air also promotes cavitation, which further destabilizes flow.

Cavitation Damage and Erosion

When high-velocity fluid passes through the valve orifice, static pressure drops according to Bernoulli's equation. If pressure falls below the oil's vapor pressure, bubbles form instantly. As these bubbles enter the downstream higher-pressure region, they collapse violently, creating microscopic jets that hammer the metal surface at tremendous velocity.

The damage appears as sponge-like pitting on the poppet and seat, usually accompanied by black discoloration from high-temperature oxidation. This erosion is irreversible and leads to severe internal leakage. Proper valve sizing to avoid excessive pressure drops and ensuring adequate back pressure can minimize cavitation risk.

Varnish Deposits and Stiction

Modern high-pressure systems face an insidious enemy: varnish. These resinous deposits form from oil oxidation at high temperatures, but also from electrostatic discharge near high-efficiency filters and from micro-dieseling when entrained air bubbles undergo adiabatic compression. This diesel-like effect creates localized hot spots that cook the oil.

Varnish preferentially deposits in tight clearances like pilot orifices and poppet guide surfaces. It increases friction, creating significant pressure hysteresis. In severe cases, the main poppet can stick in the closed position, leading to system overpressure and catastrophic burst failures. Alternatively, if the poppet sticks open, the system cannot build pressure. Prevention requires maintaining oil cleanliness per ISO 4406 codes and using anti-oxidant additives in high-temperature applications.

| Symptom | Probable Physical Cause | Diagnostic Steps |

|---|---|---|

| System cannot build pressure | Main poppet stuck open from varnish; pilot orifice blocked; vent port solenoid energized | Check X port circuit for unintended unloading; disassemble and inspect poppet freedom; verify pilot orifice flow |

| Pressure unstable or oscillating | Air entrainment in fluid; pilot stage wear or contamination; resonance with system capacitance | Check reservoir level and suction line seals; listen for squealing; inspect pilot components; measure pressure with fast-response transducer |

| High-frequency squeal | Cavitation; Helmholtz resonance in pilot chamber; air bubbles in oil | Check for inadequate back pressure; change pilot spring stiffness; degas oil or reduce aeration sources |

| Large pressure hysteresis | Mechanical friction from worn seals; varnish on sliding surfaces; incorrect PWM frequency (proportional valves) | Verify PWM dither settings; clean poppet and guides; replace aged seals |

| Pressure spike on load reversal | Response time too slow for transient; valve undersized | Add direct-acting valve in parallel for spike suppression; increase pilot drain orifice size if possible |

Installation and Maintenance Best Practices

Proper installation determines whether your hydraulic pressure relief valve performs to specification or becomes a maintenance headache.

Mounting Considerations

Most industrial hydraulic pressure relief valves follow ISO 6264 mounting standards for bolt patterns and port locations. This allows interchangeability between manufacturers, but you must verify that flow ratings and pressure ratings match your replaced component. The valve should mount as close as practical to the pump outlet for safety applications, minimizing the length of unprotected line between pump and relief valve.

Flow direction matters critically. The valve body has clear port markings: P for pressure inlet, T for tank return, and X for pilot vent (on pilot-operated models). Installing the valve backward prevents it from opening at all or causes the pilot stage to malfunction. When using sandwich plates or subplates, confirm the flow path matches the valve's internal configuration.

Adjustment and Setting Procedures

Never adjust a hydraulic pressure relief valve while the system runs under load. The correct procedure involves installing a calibrated pressure gauge directly at the valve inlet, preferably using a gauge with a snubber to dampen pulsations. Start the pump with minimal load on the system. Slowly increase the adjustment screw while watching the gauge until it reaches the desired setpoint.

For safety relief valves, set pressure approximately 10-15% above maximum system working pressure. For pressure regulating valves in fixed-displacement pump systems, the setpoint becomes your actual working pressure, so set it according to actuator force requirements. Remember that pressure override means the full-flow pressure will exceed your setpoint, especially with direct-acting valves.

Contamination Control

The ISO 4406 cleanliness code defines maximum particle counts for different size ranges. Pilot-operated hydraulic pressure relief valves with small damping orifices typically require cleanliness levels of 18/16/13 or better. This means no more than 1300 particles larger than 4 microns per milliliter. Exceeding these limits leads to pilot orifice blockage, erratic pressure control, and premature wear.

Return line filters downstream of the relief valve help prevent contamination from abrasive wear particles from re-circulating. However, the most critical filter sits on the pump inlet, preventing contamination from entering the system in the first place. Bypass indicators on filters must be checked regularly because a clogged filter creates suction-side restriction, leading to pump cavitation.

Predictive Maintenance

Modern systems increasingly use condition monitoring to predict hydraulic pressure relief valve failures before they occur. Smart valves with embedded sensors report inlet pressure, oil temperature, coil temperature, and poppet position through IO-Link or other industrial protocols. By tracking response time degradation, a control system can detect varnish buildup or spring fatigue before it causes a failure.

Even without smart valves, regular pressure-flow curve testing reveals valve degradation. Compare current full-flow pressure against baseline measurements. Increasing override pressure indicates spring fatigue or poppet wear. Decreasing cracking pressure suggests spring weakening or pilot contamination. Thermal imaging can reveal hot spots indicating excessive internal leakage or localized cavitation.

The service life of a hydraulic pressure relief valve depends heavily on duty cycle. A safety valve that rarely opens may last decades. A pressure regulating valve in continuous unloading service experiences constant flow erosion and may need rebuilding every 5000-8000 operating hours. Tracking operating hours and relief cycles helps schedule proactive maintenance before unexpected failures halt production.

Selecting the Right Hydraulic Pressure Relief Valve for Your Application

Choosing the optimal valve requires balancing multiple technical factors against cost and availability constraints.

Start with flow capacity. Calculate the maximum possible flow that needs relief, typically the pump's full output plus some safety margin. For direct-acting valves, select a nominal size where your flow falls in the middle 50-75% of the valve's range to avoid instability at either extreme. Pilot-operated designs tolerate wider flow ranges more gracefully.

Consider response time requirements. Applications with rapid load changes, like mobile equipment or cylinder deceleration, need direct-acting valves despite their higher pressure override. Steady-state pressure control in industrial systems benefits from pilot-operated designs. Some engineers use both: a pilot-operated valve for normal regulation plus a direct-acting valve set 15% higher for transient suppression.

Evaluate your contamination environment. Dirty applications like construction equipment favor direct-acting valves with their contamination tolerance. Clean industrial circuits with proper filtration can use pilot-operated designs for better performance. If you must use a pilot-operated valve in a marginal contamination environment, specify models with larger pilot orifices or those with replaceable pilot cartridges.

Account for back pressure in your calculations. If the tank return line creates significant pressure drop, this back pressure adds to the valve's cracking pressure for non-balanced designs. If back pressure exceeds 40% of setpoint, you need a pilot-operated balanced valve that compensates for return line pressure.

The operating fluid matters too. Standard hydraulic pressure relief valves work with petroleum-based hydraulic oils at temperatures from -20°C to +80°C. Water glycol fluids require special seals due to different swelling characteristics. Fire-resistant phosphate esters demand stainless steel internal components since they attack some materials. High-temperature thermal oil systems need valves rated for sustained temperatures above 100°C without seal degradation.

The Future: Smart Valves and Digital Hydraulics

The hydraulic pressure relief valve is entering a digital transformation period that promises to revolutionize system efficiency and reliability.

Smart valve technology integrates pressure transducers, temperature sensors, and position feedback directly into the valve body. These valves communicate system status via IO-Link or industrial Ethernet protocols, reporting not just whether they're relieving but also detailed performance metrics. Machine learning algorithms analyze response time trends, hysteresis changes, and thermal patterns to predict maintenance needs before failures occur.

Digital hydraulics represents an even more radical approach. Instead of using continuous throttling with proportional valves, digital systems employ arrays of fast-switching on-off valves. Binary combinations of open valves create discrete pressure or flow levels. Since each valve operates only fully open or fully closed, parasitic throttling losses nearly disappear and hysteresis becomes negligible. Response times reach sub-millisecond levels. While still expensive, this technology may eventually replace conventional hydraulic pressure relief valves in high-performance applications.

The push toward electrification, especially in mobile equipment, is reshaping hydraulic architecture. Decentralized electro-hydraulic actuators (EHAs) place small hydraulic circuits directly at each actuator, powered by individual electric motors. In these systems, the relief valve becomes primarily a safety backup while pressure control shifts to motor speed regulation. This eliminates throttling losses entirely during normal operation, dramatically improving efficiency in battery-powered machines.

These emerging technologies don't eliminate the need for traditional hydraulic pressure relief valves. They remain the most cost-effective solution for most industrial applications, particularly where reliability and simplicity outweigh the benefits of added complexity. But understanding these trends helps engineers prepare for the gradual evolution of fluid power systems toward more intelligent, efficient, and monitored architectures.

The hydraulic pressure relief valve may seem like a simple component, but as we've explored, it embodies sophisticated physics, requires careful engineering judgment for proper selection, and demands informed maintenance practices. Whether you're protecting a multi-million dollar manufacturing line or keeping a mobile machine running in harsh conditions, understanding these valves at a deeper level translates directly to better system performance, longer component life, and fewer unexpected failures.