When engineers first encounter needle valves and flow control valves in fluid power systems, they often assume these components serve identical purposes. Both regulate flow, both have adjustable elements, and both appear in hydraulic and pneumatic circuits. However, this surface-level similarity masks a fundamental operational difference that impacts system design, performance, and application suitability.

The Core Distinction: The major difference between a needle valve and a flow control valve lies in their directional flow characteristics. A needle valve restricts flow equally in both directions—it's a bi-directional throttling device. In contrast, a standard flow control valve restricts flow in only one direction while allowing free flow in the reverse direction, achieved through an integrated check valve that creates uni-directional control logic.

This distinction isn't merely academic. In a pneumatic cylinder circuit, installing a needle valve at the exhaust port would slow both the extension and retraction strokes equally, often causing insufficient inlet pressure during return. A flow control valve solves this by throttling the working stroke while permitting rapid return through its internal bypass check valve. The choice between these components fundamentally determines whether your actuator can achieve controlled motion in one direction and rapid reset in the other.

Internal Architecture: How Design Determines Function

Understanding the physical construction of these valves reveals why they behave so differently in actual systems.

Needle Valve Construction

The needle valve derives its name from its tapered stem geometry. The valve stem terminates in a long, slender cone that seats against a precision-machined orifice. This needle-and-seat arrangement creates an annular flow path whose cross-sectional area changes gradually as you rotate the stem.

The throttling mechanism forces fluid through a 90-degree turn before passing through the valve seat, similar to a globe valve configuration. This tortuous path, combined with the shallow taper angle of the needle, means that even small axial movements of the stem produce minimal changes in the flow area. Most needle valves require 8 to 10 complete turns from fully closed to fully open, giving them exceptional resolution for fine-tuning flow rates.

The sealing interface typically uses one of three approaches. Metal-to-metal seals work well for high-pressure liquids and elevated temperatures, relying on the precision contact between the hardened needle tip and seat edge. For gas applications, manufacturers often specify soft seats made from PTFE or Delrin, where the plastic material deforms under the metal needle's pressure to create a larger sealing contact area. The stem itself seals against leakage using adjustable packing glands, which introduce some mechanical friction into the adjustment mechanism.

From a flow perspective, the standard needle valve has no directional preference. Fluid entering from either port must navigate the same constricted annular passage. While manufacturers often mark flow direction arrows on the body, this recommendation primarily optimizes the pressure distribution on the packing to reduce operating torque rather than indicating a functional flow restriction.

Flow Control Valve Architecture

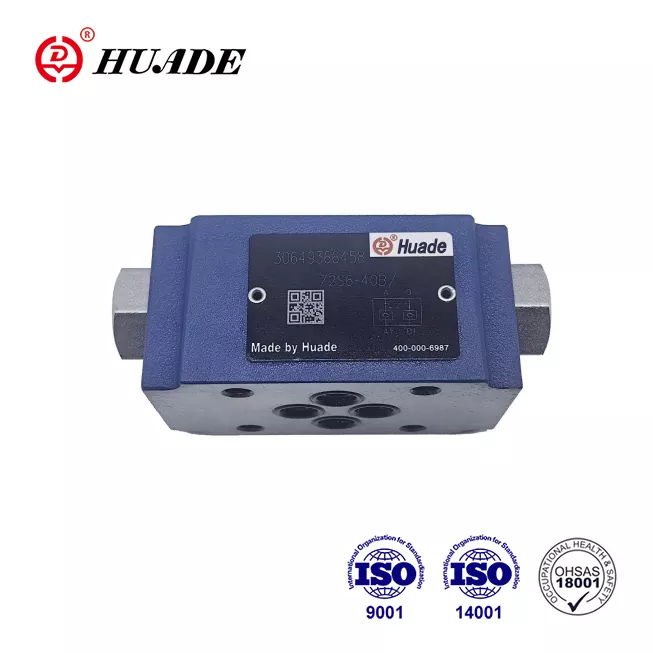

Industrial flow control valves operate as composite assemblies rather than single elements. The critical distinguishing feature is a check valve installed in parallel with the adjustable throttling section.

When fluid flows in the controlled direction, the check valve remains closed against its seat, forced shut by system pressure and its return spring. The entire flow volume must pass through the adjustable needle valve section, where the operator has set the desired restriction. This creates the metered flow path.

When system pressure reverses, fluid pressure overcomes the check valve's cracking pressure—typically between 0.5 and 7 psi depending on design—and lifts the check element off its seat. The fluid now bypasses the throttling section entirely, flowing through the much larger diameter check valve passage with minimal resistance. This creates what engineers call "free reverse flow."

This parallel circuit architecture fundamentally alters the valve's role in a system. Rather than being a simple variable restrictor, the flow control valve becomes a directional component that implements different flow resistance based on the direction of fluid movement.

| Feature | Needle Valve | Flow Control Valve |

|---|---|---|

| Core Function | Bi-directional throttling | Uni-directional throttling with bypass |

| Internal Components | Body, tapered stem, seat, packing | Body, throttling element, check valve assembly, spring |

| Flow Path Logic | Same restriction both directions | Restricted in one direction, free in reverse |

| Adjustment Range | 8-10 turns (fine pitch threads) | Variable, often with locking mechanism |

| Schematic Symbol | Throttle orifice with bilateral arrows | Throttle orifice in parallel with check valve |

Fluid Dynamic Behavior Under Load

The way these valves respond to changing system pressures reveals their fundamental operational differences and determines their suitability for specific applications.

The Orifice Equation and Load Sensitivity

Both needle valves and basic non-compensated flow control valves obey the same underlying physics described by the orifice flow equation:

Here, flow rate Q depends on the discharge coefficient Cd, the orifice area A (which you set by adjusting the valve), the pressure differential ΔP across the valve, and the fluid density ρ.

The critical insight comes from that square root relationship with pressure differential. Consider a hydraulic cylinder controlled by a needle valve. When the cylinder encounters increased load—perhaps lifting a heavier object—the pressure required downstream of the valve (Pout) must rise to overcome that load. If inlet pressure (Pin) remains constant from the pump, then the pressure drop across the valve (ΔP = Pin - Pout) necessarily decreases.

According to the equation, when ΔP drops, flow rate Q drops proportionally to the square root of that change. The practical result is that your cylinder slows down when it encounters heavier loads and speeds up with lighter loads. This load-dependent behavior makes simple needle valves unsuitable for applications requiring constant speed under varying loads, such as machine tool feed drives where cutting forces fluctuate.

Pressure Compensation: Breaking the Load Dependency

Advanced hydraulic flow control valves incorporate pressure compensation mechanisms to maintain constant flow regardless of load variations. These designs use a movable compensator spool that automatically adjusts its opening in response to pressure changes.

The compensator creates a two-stage throttling system. First, fluid passes through your manually adjustable control orifice, which sets the target flow rate. Downstream of this control orifice, the pressure drops to some intermediate level. A spring-loaded spool senses the pressure both upstream and downstream of the control orifice.

The force balance on this compensator spool can be expressed as:

Rearranging this equation shows that the pressure drop across the control orifice becomes:

The spring force and spool area are fixed design parameters. This means the compensator automatically adjusts its own restriction to maintain a constant pressure differential across your control orifice, regardless of downstream load pressure. When you substitute this constant ΔP back into the orifice equation, flow rate depends only on the orifice area you've set—the load pressure no longer affects actuator speed.

This pressure compensation distinguishes industrial-grade flow control valves from simple needle valves. A needle valve cannot provide this load-independent flow regulation because it lacks the feedback mechanism to sense and respond to pressure changes.

Application Logic in Pneumatic Systems

The difference between needle valves and flow control valves becomes most apparent in pneumatic actuator circuits, where the compressibility of air creates unique control challenges.

Meter-Out Control: The Pneumatic Standard

In pneumatic systems, engineers almost universally apply flow control valves using meter-out configuration. The valve installs at the cylinder exhaust port, not the inlet. Full-pressure air enters freely through the inlet side, while the exhaust air must push through the restricted orifice of the flow control valve.

This arrangement creates back pressure in the exhaust chamber of the cylinder. That trapped, compressed air acts like a pneumatic spring-damper, cushioning the piston and preventing it from lurching forward erratically when the inlet receives pressure. Even with varying loads or supply pressure fluctuations, the controlled exhaust rate keeps piston velocity smooth and predictable.

The meter-out approach specifically requires a valve with directional logic. During the working stroke—say, extending a cylinder—air exhausts through the throttled path, controlling speed. But when you reverse the valve to retract the cylinder, that same port now becomes the inlet. If you used a plain needle valve, the inlet air would also be throttled, starving the cylinder of supply pressure and dramatically reducing both speed and output force on the return stroke.

A flow control valve with an integrated check valve solves this elegantly. On the return stroke, inlet air pressure opens the check valve, bypassing the throttle and flooding the cylinder with full-pressure air for rapid retraction. You get controlled motion in one direction and fast return in the other, using a single component.

Why Needle Valves Fail in Cylinder Control

Installing a needle valve at a cylinder exhaust port creates symmetric restriction. The working stroke proceeds at your desired controlled speed as exhaust air battles through the needle valve's restriction. But attempting to reverse direction reveals the problem—the cylinder now tries to pull air in through that same restriction.

The inlet throttling reduces available pressure, and worse, air's compressibility means the cylinder will exhibit stick-slip motion or fail to develop sufficient force. In applications with overrunning loads, like vertical cylinders extending downward, the uncontrolled inlet can allow the load to freefall while the cylinder chamber struggles to fill through the restriction.

Needle valves do find specific pneumatic applications, particularly in instrument airlines, pilot pressure adjustment, and laboratory flow metering where you actually need bi-directional restriction or where the flow is unidirectional by circuit design. But for standard actuator speed control, the flow control valve's directional logic is essential.

Hydraulic System Considerations

Hydraulic applications emphasize different valve characteristics than pneumatic systems, primarily because hydraulic fluid is incompressible and systems operate at much higher pressures.

Constant Speed Requirements

Hydraulic motors driving conveyor belts, winches, or machine tool feed axes typically encounter variable loads throughout their operating cycle. A forklift's hydraulic lift motor experiences different resistance when raising an empty pallet versus a loaded one. A milling machine's feed motor sees cutting forces that vary with material hardness and depth of cut.

If you control such applications with a simple needle valve, the load-dependent flow behavior becomes problematic. Heavier loads increase downstream pressure, reduce the pressure differential across the needle valve, and slow the motor down precisely when you need consistent speed. This speed variation causes poor surface finish in machining, uneven material feed in continuous processes, and unpredictable positioning in material handling.

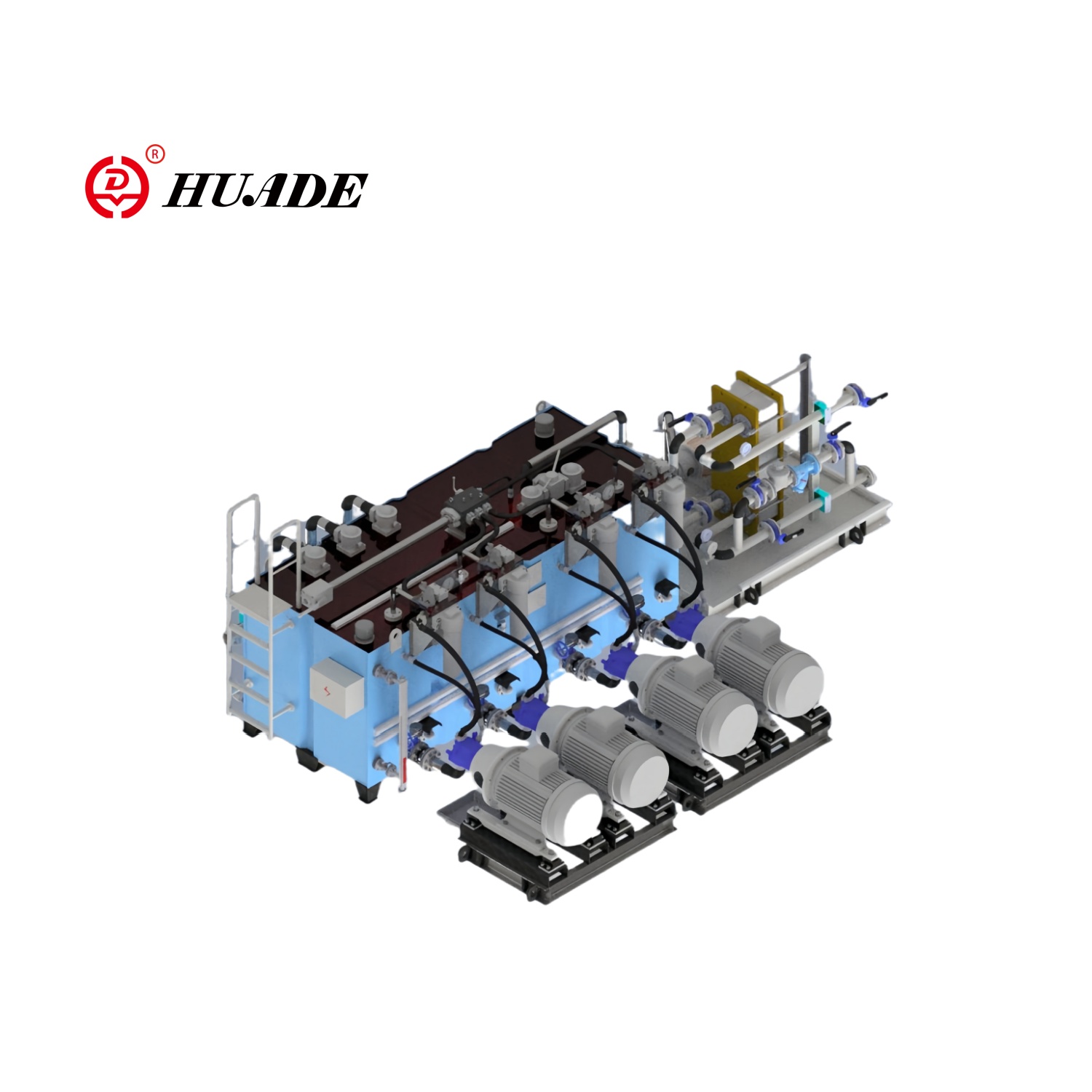

Pressure-compensated flow control valves maintain constant flow—and therefore constant motor speed—regardless of load variations. The compensator continuously adjusts to hold fixed pressure drop across the metering element, implementing the constant-flow principle described earlier. This makes pressure-compensated flow control valves standard equipment in industrial hydraulic circuits requiring load-independent speed regulation.

Energy Management and Heat Generation

Hydraulic systems must manage energy dissipation carefully. All throttling-type flow control, whether using needle valves or flow control valves, converts excess hydraulic power into heat. The pressure drop across the restriction multiplied by flow rate equals the power wasted as heat generation.

Three-port priority flow control valves address this by incorporating a bypass port. These valves meter the required flow to the actuator while diverting excess pump flow back to tank at low pressure, rather than forcing all pump output across a high-pressure relief valve. This reduces heat generation in the hydraulic reservoir and improves overall system efficiency.

Needle valves serve a different hydraulic role as pressure gauge snubbers. When installed between a pressure source and a gauge, a nearly-closed needle valve creates enormous flow resistance that filters out pressure spikes and pulsations. This protects sensitive pressure instruments from impact damage due to water hammer effects. Here, you're exploiting the needle valve's high throttling capability and fine adjustment, not its flow control characteristics.

Performance Specifications and Selection Criteria

Beyond the functional differences, these valve types exhibit distinct performance characteristics that influence engineering decisions.

Adjustment Resolution and Linearity

Needle valves excel at providing fine, linear control over small flow adjustments. The combination of shallow taper angle and fine-pitch threads creates a near-linear relationship between handle rotation and flow coefficient over the initial turns of opening. A quality needle valve might deliver flow changes as small as 0.1% of maximum flow per degree of rotation.

This resolution makes needle valves ideal for setting pilot pressures, calibrating flow rates in analytical instruments, or establishing reference conditions in test systems. Once you achieve the desired setting, a locking handle or locknut maintains that position indefinitely.

Hysteresis and Deadband in Flow Control Valves

Flow control valves with moving internal components—particularly the check valve assembly and any compensator spools—introduce hysteresis into the flow adjustment. Hysteresis means the valve delivers different flow rates at the same adjustment setting depending on whether you approached that setting from below or above.

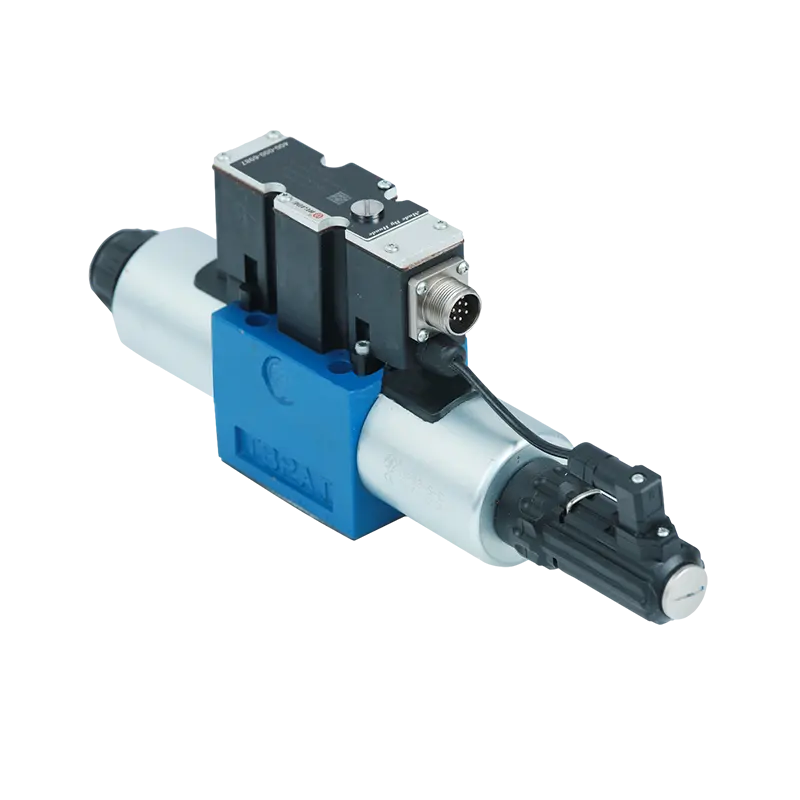

Mechanical sources of hysteresis include packing friction, O-ring stiction, and spring non-linearity. In manually adjusted valves, this might represent 2-5% of full-scale flow. Proportional electrohydraulic flow control valves can exhibit higher hysteresis, sometimes 7-10%, due to magnetic hysteresis in the solenoid and mechanical friction in the spool assembly.

Deadband refers to the range of input adjustment over which no flow change occurs. Some flow control valves show significant deadband near the closed position to ensure zero leakage when commanded shut—values can reach 40-50% of signal range. Needle valves typically have minimal deadband since flow begins immediately when the needle lifts off its seat, though this makes them more sensitive to contamination near the closed position.

| Performance Metric | Needle Valve | Flow Control Valve |

|---|---|---|

| Adjustment Linearity | Excellent | Good (some non-linearity) |

| Resolution | Very high | Moderate |

| Hysteresis | Low | Moderate to high |

| Deadband | Minimal | Can be significant |

| Load Independence | None | Basic to Excellent (Compensated) |

| Adjustment Stability | Excellent once locked | Good |

Terminology and Industry Context

The terms "needle valve" and "flow control valve" carry different meanings across industries, which can create confusion during cross-disciplinary communication.

In the general industrial fluid power sector—covering hydraulics and pneumatics—the definitions presented here apply consistently. Needle valves are fine-adjustment throttling devices, and flow control valves are directional metering components with integrated check valves or compensation.

However, in semiconductor manufacturing, "flow control valve" typically refers to mass flow controllers (MFCs) that precisely regulate process gas delivery using closed-loop electronic control. Meanwhile, "throttle valve" in that context describes the butterfly or gate valve at the vacuum pump inlet that controls chamber pressure by varying pumping conductance, not flow rate.

In automotive engineering, "throttle valve" commonly means the engine air intake butterfly valve that controls power output. This has nothing to do with hydraulic or pneumatic flow control valves despite sharing terminology.

When specifying components or reviewing technical literature, always verify the industry context and confirm the specific valve configuration rather than relying solely on terminology.

Selection Decision Framework

Choosing between these valve types requires analyzing your specific application requirements against the fundamental capabilities of each design.

Select a Flow Control Valve when:

- Your application involves pneumatic or hydraulic cylinder speed control where you need controlled motion in one direction and rapid return in the opposite direction.

- You need directional flow logic where one direction must be metered and the other must flow freely.

- Typical uses: Sequencing circuits, regenerative cylinder circuits.

Select a Pressure-Compensated Flow Control Valve when:

- Load variations significantly affect downstream pressure, but you must maintain constant actuator speed (e.g., Machine tool feeds, conveyor drives).

- Multiple actuators share a common pressure source, and you need each actuator to maintain its set speed regardless of the others' activities.

Select a Needle Valve when:

- You need extremely fine flow adjustment resolution for calibration, testing, or instrumentation applications.

- Bi-directional flow restriction serves your purpose (e.g., pressure gauge snubbing, instrument air damping).

- System pressures exceed the rating of standard flow control valves (high-pressure gas systems).

- Your application involves corrosive or high-temperature fluids where simpler construction offers better reliability.

The most critical insight is recognizing that while both valves restrict flow, they serve fundamentally different control purposes. A needle valve is a precision variable restrictor—a tool for fine-tuning static operating points. A flow control valve is a dynamic control element that implements directional logic and, in advanced forms, maintains flow constancy despite system disturbances. Understanding this distinction prevents the common mistake of using a simple needle valve where directional control or load compensation is actually required.