Selecting the right flow control valve for your hydraulic system is not just about picking a component from a catalog. This decision directly impacts the speed consistency of your actuators, system heat generation, and overall energy efficiency. Many engineers face a common challenge: their hydraulic cylinder moves too fast under light loads and slows down when resistance increases. This happens because the wrong valve was chosen, or more precisely, the fundamental relationship between pressure drop and flow rate was misunderstood.

When you choose a flow control valve for a hydraulic system, you are essentially deciding how to manage energy conversion. Every valve that throttles flow is consuming hydraulic power and converting it into heat. The heat must go somewhere, and if your calculations are wrong, you will face oil degradation, seal failures, and premature component wear. This is why understanding the physical principles behind flow control is critical before you even look at a product specification sheet.

Understanding Flow Control Fundamentals

The basic purpose of a flow control valve is to regulate the volume flow rate of hydraulic fluid reaching an actuator, which directly controls its linear or rotational speed. However, this simple goal involves complex fluid dynamics. The flow through an orifice follows the Bernoulli equation, where flow rate Q is proportional to the square root of the pressure drop across the valve:

In this equation, Cd represents the discharge coefficient (typically determined experimentally), A is the orifice area, Δp is the pressure differential, and ρ is fluid density.

This square root relationship creates a fundamental problem: if your load changes and causes the downstream pressure to vary, the flow rate will change even though you did not touch the valve adjustment. This is called load sensitivity, and it is the main reason why simple throttle valves often fail to maintain consistent actuator speed.

The Reynolds number determines whether flow through your valve is laminar or turbulent. When operating with high viscosity oil at low temperatures, flow may become laminar, especially in needle valves with long, narrow passages. In laminar conditions, flow rate becomes inversely proportional to viscosity, which means your actuator speed will drift significantly as the system warms up. Modern precision flow control valves use sharp-edged orifices to force turbulent flow even at moderate Reynolds numbers. This design makes the discharge coefficient Cd relatively constant across a wide viscosity range, minimizing thermal drift.

Key Selection Criteria

Flow Requirements and Cv Value Calculation

The first technical decision when you choose a flow control valve for a hydraulic system is determining the required flow coefficient. In North America, this is expressed as Cv (flow in US gallons per minute at 1 psi pressure drop with 60°F water). European standards use Kv (flow in cubic meters per hour at 1 bar pressure drop). The conversion is straightforward: Cv ≈ 1.16 × Kv.

Since hydraulic oil has a specific gravity around 0.85 to 0.9, you need to apply correction factors. The practical formula becomes:

However, there is a critical mistake many engineers make: they size the valve based on 100% flow at full valve opening. This creates terrible control characteristics. Your valve should operate between 30% and 70% of its maximum Cv at the design point. If the valve reaches your required flow at only 10% opening, you will experience wire drawing erosion and extremely poor resolution in speed control. Conversely, if the valve must be at 95% opening to achieve the desired flow, you are generating excessive pressure drop, wasting energy, and creating unnecessary heat.

Pressure and Temperature Ratings

Every flow control valve has maximum working pressure and temperature limits determined by its body construction and seal materials. When you choose a flow control valve for a hydraulic system, you must account for both steady-state and transient pressure spikes. Pressure transients can reach 2 to 3 times the normal operating pressure during rapid directional valve switching or pump start-up.

Temperature affects more than just the valve body. Oil viscosity changes dramatically with temperature. Mineral-based hydraulic oils can lose half their viscosity with every 10°C temperature increase. This is why precision applications require either temperature-compensated valves (which use bimetallic elements to mechanically adjust the orifice as temperature changes) or operation within a tightly controlled temperature window.

Fluid Compatibility and Contamination Sensitivity

The hydraulic fluid type determines seal material selection. Using incompatible seals leads to catastrophic failure within hours. Nitrile rubber (NBR or Buna-N) works well with mineral oils but will harden and crack when exposed to phosphate ester fire-resistant fluids. Conversely, EPDM rubber, which is required for phosphate ester fluids like Skydrol in aerospace applications, will swell and fail rapidly in mineral oil. Fluorocarbon rubber (FKM or Viton) offers broader chemical compatibility and higher temperature tolerance up to 200°C, but costs significantly more.

Contamination sensitivity varies dramatically between valve types. Servo valves with jet pipe or nozzle-flapper pilot stages have orifices measured in microns. They require oil cleanliness levels of ISO 4406 15/13/10 or better. Proportional valves with direct-acting solenoids tolerate ISO 4406 18/16/13. Standard industrial flow control valves can typically operate at 19/17/14, though performance degrades as particles accumulate on the spool, increasing friction and causing stiction.

Seal Material Compatibility with Common Hydraulic Fluids

| Seal Material | Mineral Oil | Phosphate Ester | Water Glycol | Temp Range (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBR (Buna-N) | Excellent | Not Compatible | Good | -30 to +100 |

| FKM (Viton) | Excellent | Good | Fair | -20 to +200 |

| EPDM | Not Compatible | Excellent | Excellent | -40 to +120 |

Valve Types and Their Applications

Non-Compensated Throttle Valves

The simplest flow control device is a basic throttle valve, which is just a variable restriction. Needle valves use a tapered spool moving within a seat to create an adjustable annular gap. They excel at very fine flow adjustments but are extremely sensitive to viscosity changes because their long, narrow passages promote laminar flow. Ball valves and gate valves are typically on-off devices. When used for throttling, their high gain characteristic (small movement causes large flow change) and tendency to cavitate make them unsuitable for precision control.

When you choose a flow control valve for a hydraulic system with constant loads and relaxed speed accuracy requirements, a simple throttle can work. However, any load variation will cause proportional speed changes because the pressure drop across the valve changes, and flow follows that square root relationship we discussed earlier.

Pressure-Compensated Flow Control Valves

To eliminate load sensitivity, pressure-compensated valves incorporate a differential pressure regulator in series with the main throttling orifice. This regulator is essentially a spring-loaded spool that senses pressure both upstream and downstream of the main orifice. The compensator automatically adjusts its opening to maintain a constant pressure drop across the main orifice regardless of system pressure or load pressure fluctuations.

The force balance on the compensator spool can be expressed as:

This simplifies to maintain a constant differential: p₂ - p₃ = constant (typically 5 to 10 bar). Since the pressure drop Δp is now constant and the orifice area A is set by your adjustment, the flow Q becomes independent of load changes.

There are two compensation configurations. Two-way flow control valves place the compensator in series with the flow path. They deliver precise flow to the actuator, but excess pump flow must return to tank through the system relief valve at full pressure, wasting significant energy. Three-way flow control valves use the compensator as a bypass valve. Excess flow returns to tank at load pressure plus the compensator spring pressure, not at relief pressure. In fixed displacement pump systems, three-way valves are substantially more energy-efficient.

Circuit Topology Considerations

Where you install the flow control valve in your circuit fundamentally changes system behavior. This is one of the most misunderstood aspects when engineers choose a flow control valve for a hydraulic system.

Meter-in control places the valve between the pump and actuator inlet. This configuration works well for resistive loads where force opposes motion, like lifting a weight. However, meter-in control is completely ineffective and dangerous for overrunning loads. If your load direction matches motion direction (lowering a heavy load or a drill bit suddenly breaking through material), the load will pull the actuator faster than oil is being supplied. This creates vacuum conditions in the cylinder, causes cavitation, and results in runaway speed that can destroy equipment or injure operators.

Meter-out control installs the valve between the actuator outlet and tank. The pump applies full pressure to the inlet side while the flow control valve creates backpressure on the outlet side. The actuator is squeezed between inlet pressure and outlet backpressure, creating extremely high system stiffness and smooth motion. Meter-out prevents runaway conditions with overrunning loads because the actuator physically cannot move faster than oil is allowed to exit.

However, meter-out circuit topology introduces a serious risk called pressure intensification. In a single-rod cylinder, the cap-end area (piston area) is larger than the rod-end area. During extension with meter-out control, if the cap-end pressure is p₁ and the area ratio φ = A_cap/A_rod is 2:1 (common design), the rod-end pressure can theoretically reach 2 × p₁ even with zero load. This can exceed the pressure rating of seals, tube fittings, or the valve body itself. You must verify that all components in the rod-end circuit can handle this intensified pressure.

Bleed-off control places the valve on a branch line that diverts some pump flow directly to tank. The actuator receives pump flow minus bypass flow. This configuration is the most energy-efficient because system pressure equals only what the load requires. However, it has the worst speed stiffness. If load increases, system pressure rises, which increases flow through the bypass valve (unless it is pressure-compensated), reducing flow to the actuator and slowing it down.

Comparison of Flow Control Circuit Topologies

| Characteristic | Meter-In | Meter-Out | Bleed-Off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Load Type Suitability | Resistive only | Resistive & Overrunning | Constant resistive |

| System Stiffness | Medium | High | Low |

| Energy Efficiency | Low | Low | High |

| Cavitation Risk | High (overrunning loads) | Low | Medium |

| Pressure Intensification Risk | None | High (rod-end side) | None |

Sizing and Calculation Methods

Proper sizing requires calculating the actual flow rate needed based on actuator geometry and desired speed. For a hydraulic cylinder, flow rate equals piston area multiplied by velocity:

Convert units carefully. If you need a cylinder with 100 mm bore diameter to extend at 50 mm/s, the piston area is 0.00785 m², giving a flow rate of 0.000393 m³/s or 23.6 liters per minute. Adding 15% margin for system losses, you would target a valve that can deliver approximately 27 liters per minute at your design pressure drop.

The allowable pressure drop across your flow control valve depends on your system's thermal management capability. Every bar of pressure drop consumes power equal to Q (liters/min) × Δp (bar) / 600 = kW. For our example at 27 L/min, a 10 bar pressure drop generates 0.45 kW of heat continuously. Your reservoir, cooler, and ambient conditions must be able to dissipate this heat without exceeding your maximum allowable oil temperature, typically 60°C to 70°C for mineral oils with standard seals.

Cavitation becomes a risk when pressure at the valve's vena contracta (point of minimum area and maximum velocity) drops below the fluid's vapor pressure. The cavitation index sigma provides a quantitative check:

Safe operation requires σ > 2.0. When σ drops below 1.0, cavitation becomes likely. Below σ = 0.2, choked flow occurs where further pressure drop increases do not increase flow, accompanied by severe noise and erosion damage. In meter-out circuits where downstream pressure approaches zero (tank pressure), sigma values can be critically low, requiring multi-stage pressure reduction designs.

Installation Standards and Material Selection

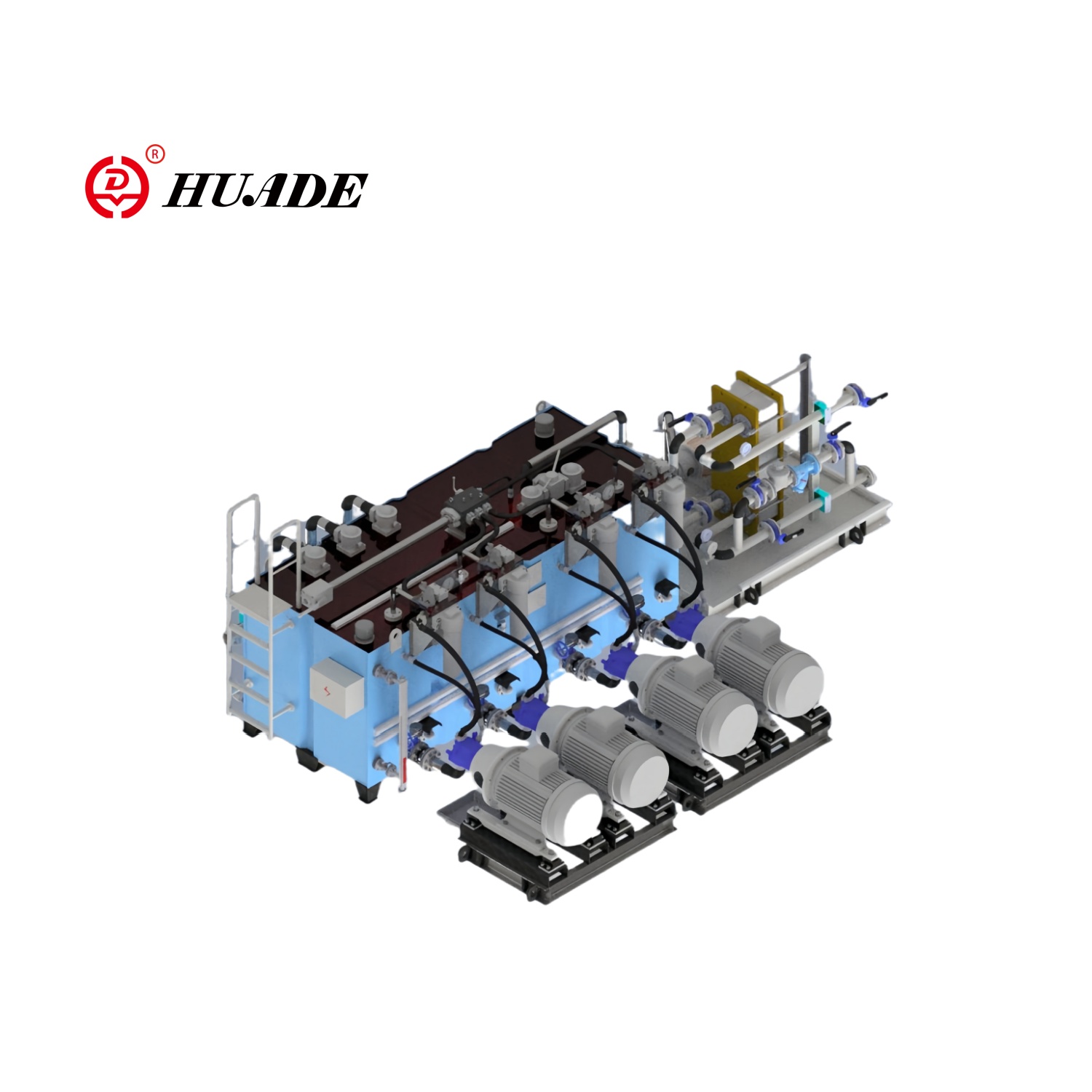

Physical installation method affects system reliability and maintenance accessibility. Line-mounted valves thread directly into pipe fittings. They work for simple systems but create maintenance difficulties because you must break hydraulic connections to service them. Subplate mounting using ISO 4401 or CETOP standards is the industrial norm. Valves bolt onto ported mounting surfaces with standardized bolt patterns and port locations.

CETOP 3 (also called NG6 or Size 03) handles flows typically up to 60-80 L/min. CETOP 5 (NG10, Size 05) works up to 120 L/min. CETOP 8 (NG25, Size 08) can pass 700 L/min. This standardization allows you to substitute valves from different manufacturers (Bosch Rexroth, Parker, Eaton, others) using the same mounting footprint, simplifying design and reducing spare parts inventory.

Cartridge valves (also called logic valves) are inserted into machined cavities in manifold blocks. Common sizes follow SAE standards: SAE-08, SAE-10, SAE-12, SAE-16. Cartridge designs offer maximum compactness, eliminate external leakage paths, and provide superior vibration resistance. They are the preferred choice for mobile equipment like excavators and wheel loaders where space is limited and environmental conditions are harsh.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid When You Choose a Flow Control Valve

One frequent mistake is ignoring the valve authority concept. If you size a valve based on achieving full design flow at 100% valve opening, you effectively have no flow control. The usable range where you can make fine adjustments may only be the first 5% of handle rotation. Instead, target your design flow to occur at 50% valve opening. This centers your operating point and provides good control resolution in both directions.

Another critical error is failing to account for worst-case pressure conditions. When you choose a flow control valve for a hydraulic system, you must calculate pressures under maximum load, minimum load, cold start conditions, and transient shock scenarios. The pressure intensification phenomenon in meter-out circuits catches many designers. A 100 bar system pressure with a 2:1 area ratio cylinder can create 200 bar on the rod-end side. If your valve or fittings are only rated for 150 bar, failure is inevitable.

Temperature drift compensation is often overlooked. Even valves designed with sharp-edged orifices for turbulent flow show some viscosity sensitivity. In applications requiring speed consistency within 2-3% across temperature ranges from 20°C to 60°C, you need either active temperature compensation using bimetallic elements or closed-loop electronic control with proportional valves. Simply hoping your throttle valve will maintain speed is not engineering.

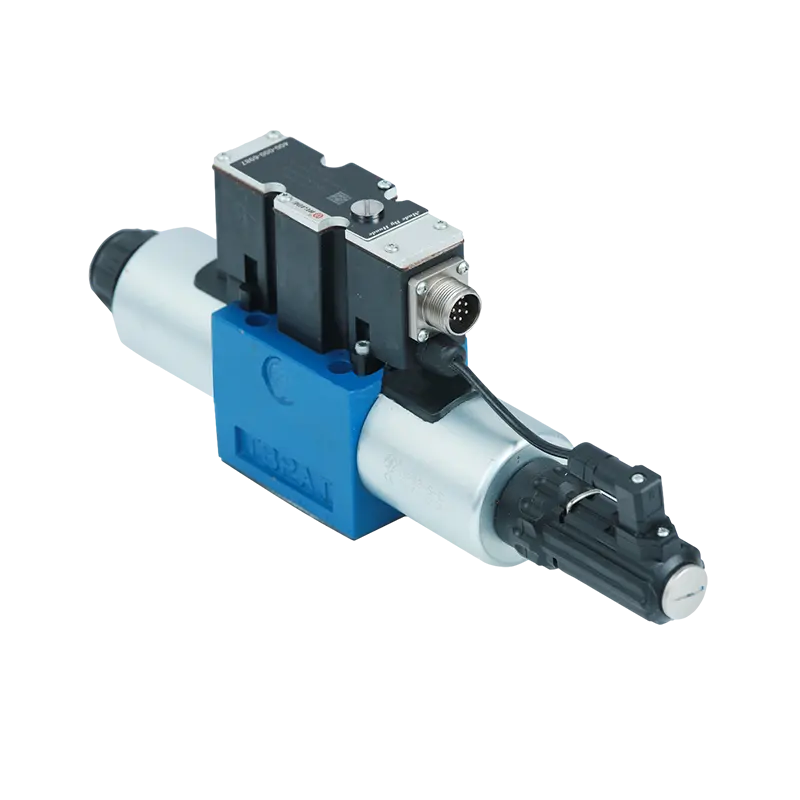

The question of when to upgrade from manual throttle valves to proportional or servo valves depends on your performance requirements. Proportional valves with pulse-width modulation (PWM) drive and dither signals eliminate stiction and can achieve hysteresis below 3% for open-loop types or under 0.5% for closed-loop versions with LVDT position feedback. Their frequency response reaches 50 Hz or higher. This performance level handles most industrial automation tasks. Servo valves with torque motors and jet pipe or nozzle-flapper pilot stages offer frequency response exceeding 100 Hz and near-zero deadband, but they demand extremely high oil cleanliness (ISO 4406 15/13/10 minimum) and cost significantly more. Reserve servo valves for applications with genuinely demanding dynamic requirements like flight simulators or materials testing machines.

Making Your Final Selection Decision

When you choose a flow control valve for a hydraulic system, you are balancing multiple competing objectives: control precision, energy efficiency, system stiffness, cost, and maintainability. Start by clearly defining your control objective. Do you need constant speed regardless of load (choose pressure-compensated valve), synchronized motion of multiple actuators (choose flow divider), or programmable speed profiles (choose proportional valve with electronic control)?

Analyze your load characteristics carefully. Resistive loads allow meter-in control. Overrunning loads require meter-out control, which means you must verify pressure intensification will not exceed component ratings. Energy-conscious designs with constant loads benefit from bleed-off control or load-sensing systems. Calculate the required flow rate from actuator geometry and desired speed, then determine the Cv value that places your operating point between 30% and 70% valve opening at the expected pressure drop.

Select installation method based on space constraints and maintenance philosophy. Choose seal materials compatible with your hydraulic fluid and temperature range. Verify that contamination control meets valve sensitivity requirements. If your application involves rapidly changing loads or closed-loop position control, proportional valves become necessary, and you must ensure the drive amplifier provides proper PWM frequency and dither signal characteristics.

The physical principles governing flow control have not changed, but the tools available to implement control strategies have evolved significantly. Modern pressure-compensated valves with temperature correction elements can maintain speed within 5% across wide operating ranges. Closed-loop proportional valves with integral electronics bridge the gap between simple manual valves and expensive servo systems. Digital protocols like IO-Link enable remote configuration and predictive maintenance by monitoring current signatures for early detection of spool stiction.

Success in flow control valve selection requires understanding that every valve throttles by creating pressure drop, and pressure drop multiplied by flow rate equals wasted power converted to heat. Your goal is to achieve the required control precision with minimum energy consumption and heat generation. This demands careful calculation, not guesswork. When you choose a flow control valve for a hydraulic system using the systematic approach outlined here, you will avoid costly mistakes like cavitation damage, runaway actuators, and thermal failures, while maximizing system performance and energy efficiency.