When you open a hydraulic circuit diagram or a process flow drawing, throttle valve symbols appear as simple geometric shapes. But these lines and angles carry critical information about how fluid flows, how systems respond to load changes, and where safety risks might hide. A single misread symbol could mean the difference between a machine that smoothly lifts heavy loads and one that drops them catastrophically.

The throttle valve symbol represents more than just a component on paper. It encodes the physical behavior of fluid restriction, the mathematical relationship between pressure drop and flow rate, and the control strategy an engineer has chosen for that specific point in the system. Understanding these symbols requires knowing which standard your drawing follows, what each geometric feature means in terms of fluid mechanics, and how symbol placement affects system performance.

Two Worlds: ISO 1219 and ANSI/ISA-5.1 Standard Systems

The first challenge in reading throttle valve symbols is recognizing that two completely different symbolic languages dominate industrial practice. ISO 1219 standards govern fluid power systems (hydraulics and pneumatics), while ANSI/ISA-5.1 standards rule process instrumentation and control. These aren't just different drawing styles. They represent different engineering philosophies about what information matters most.

ISO 1219 follows a functional abstraction approach. The standard, currently at ISO 1219-1:2012, uses basic geometric primitives like squares, circles, and lines to represent component functions rather than physical shapes. A throttle valve in ISO notation doesn't look like a real valve body. Instead, it shows up as a constriction in the flow path, directly representing its role as a flow restriction element. This makes sense when you consider the governing equation: flow rate Q equals the discharge coefficient Cd times the orifice area A times the square root of two times pressure drop divided by fluid density. The symbol's narrowed passage visually maps to that restricted area A in the formula.

The Chinese national standard GB/T 786.1-2021 adopts ISO 1219 with high fidelity, emphasizing universal comprehension across language barriers. When you see these symbols, you're reading a language designed for mobile equipment, construction machinery, and automated production lines where hydraulic cylinders and motors dominate.

ANSI/ISA-5.1 takes a different path. Process and Instrumentation Diagrams (P&IDs) in chemical plants, refineries, and power stations use symbols that preserve equipment identity. The standard bow-tie symbol for valves mimics the physical connection of flanges to pipe runs. A throttle valve in this context often appears as a globe valve symbol (bow-tie with a solid dot in the center) or carries specific actuator markings that identify it as a control valve. The emphasis shifts from "what it does to the fluid" to "what type of equipment this is" and "how is it actuated."

| Aspect | ISO 1219 (Fluid Power) | ANSI/ISA-5.1 (Process Control) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Hydraulic systems, pneumatic automation, mobile machinery | Chemical processing, refineries, water treatment, power plants |

| Design Philosophy | Functional abstraction | Equipment identity and instrumentation loops |

| Basic Valve Shape | Square or rectangle | Bow-tie (two opposing triangles) |

| Throttle Representation | Narrowed flow path with angle lines | Globe valve body or control valve assembly |

| Line Meaning | Solid = working fluid, dashed = pilot control | Solid = process piping, dashed = signal lines |

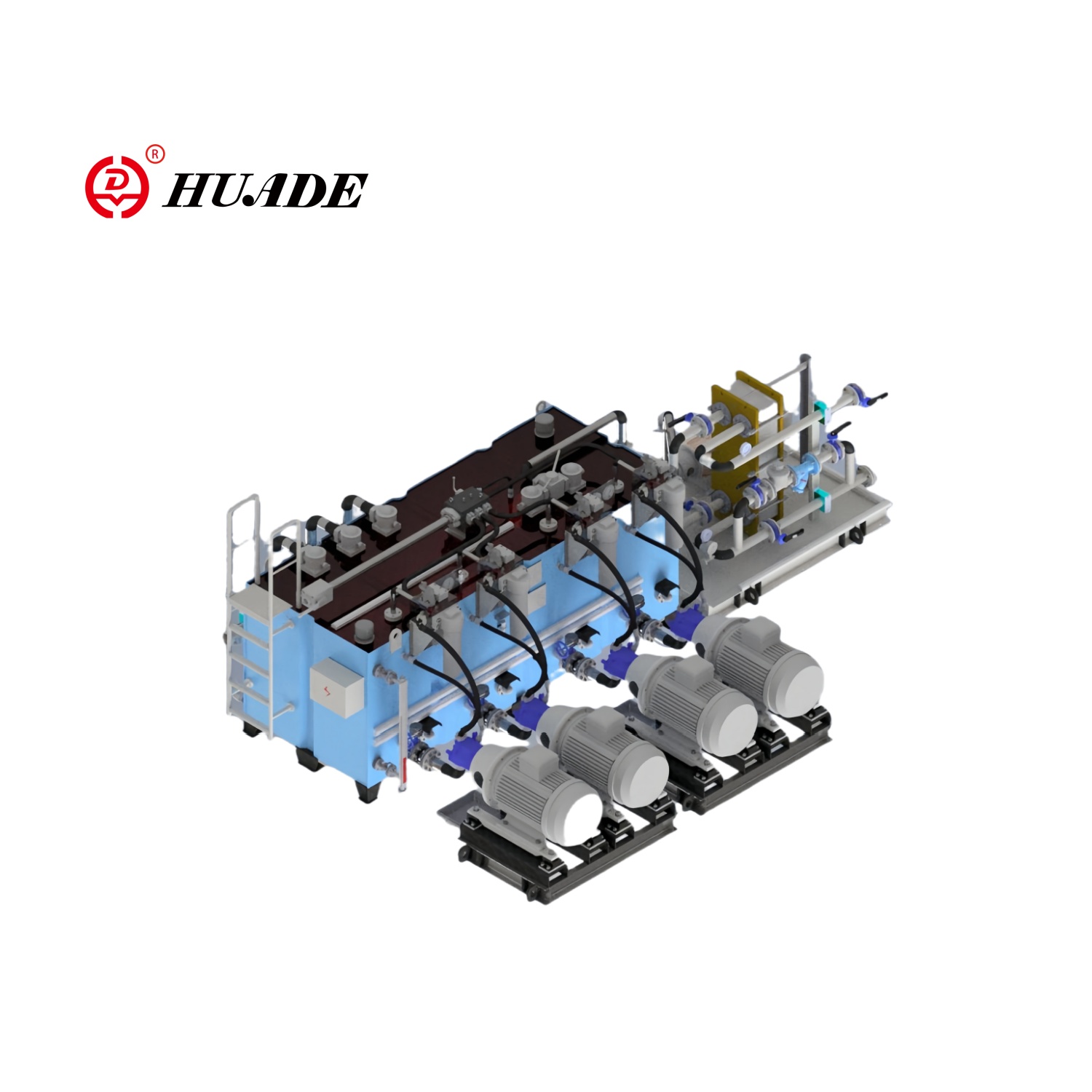

Mixing these standards on one drawing creates confusion. A hydraulic power unit schematic should strictly follow ISO 1219. A plant-wide process flow diagram connecting to a distributed control system should use ISA 5.1. When you must show detailed hydraulic control on a P&ID, the drawing legend must explicitly declare which convention applies to which section.

Decoding ISO 1219 Throttle Valve Symbols

The ISO throttle valve symbol starts with a basic restriction element. Two inward-angled lines pinch the flow path, creating a visual narrowing that directly represents the reduced cross-sectional area where fluid accelerates. This isn't arbitrary geometry. When fluid passes through this constriction, Bernoulli's principle tells us velocity increases and pressure drops. The flow rate becomes a function of both the orifice area and the pressure differential across it.

A diagonal arrow crossing through the valve body adds adjustability. Without this arrow, you're looking at a fixed orifice, typically used for damping in pilot circuits or as a buffer at pressure gauge connections to prevent needle flutter. The diagonal arrow means the valve spindle can move, changing the effective flow area. This corresponds to needle valves or manually adjusted throttle cartridges in real hardware.

You must distinguish this adjustment arrow from directional flow arrows. The diagonal arrow traverses the component symbol itself, indicating variability of state. Flow direction arrows appear at line ends, showing which way the fluid moves. Confusing these is a common mistake among technicians new to hydraulic schematics.

Viscosity Dependency: Curves Versus Angles

A subtle but critical detail in ISO 1219 symbols is the shape of the restriction lines. This relates directly to Reynolds number and flow regime.

- Curved Lines (Parentheses Shape): When the throttle symbol uses smooth curved lines, it indicates viscosity-dependent behavior. This represents a long, narrow passage where laminar flow dominates. The Hagen-Poiseuille law applies: flow rate depends inversely on fluid dynamic viscosity. As hydraulic oil heats up during operation, viscosity drops, and flow through this valve increases noticeably. Your actuator speeds up as the system warms.

- Sharp Angles (Chevron Shape): When the symbol shows sharp angles or opposing right angles, it signals viscosity-independent behavior. This represents a thin-wall orifice or sharp-edged restriction where fluid passes through an extremely short constriction. Inertial pressure losses dominate, and the flow becomes turbulent. Viscosity changes have minimal effect on the pressure-flow relationship within normal operating temperature ranges.

This distinction matters enormously for precision speed control applications where thermal stability is critical. Many generic CAD symbol libraries ignore this nuance, leading to drawings that fail to communicate the designer's thermal compensation strategy. Professional hydraulic schematics must preserve this distinction rigorously.

Actuation Method Annotations

ISO symbols show how the throttle valve is adjusted by adding notations to the basic rectangle. A manual handwheel appears as a perpendicular short line or wheel symbol at the adjustment arrow's end. Spring return mechanisms show as sawtooth zigzag lines on one side of the valve body, indicating the spindle resets to a default position when external force is removed. Roller or cam followers appear as circles touching a line, representing travel-dependent throttles where mechanical position drives valve opening (common in machine tool feed systems for automatic deceleration sequences).

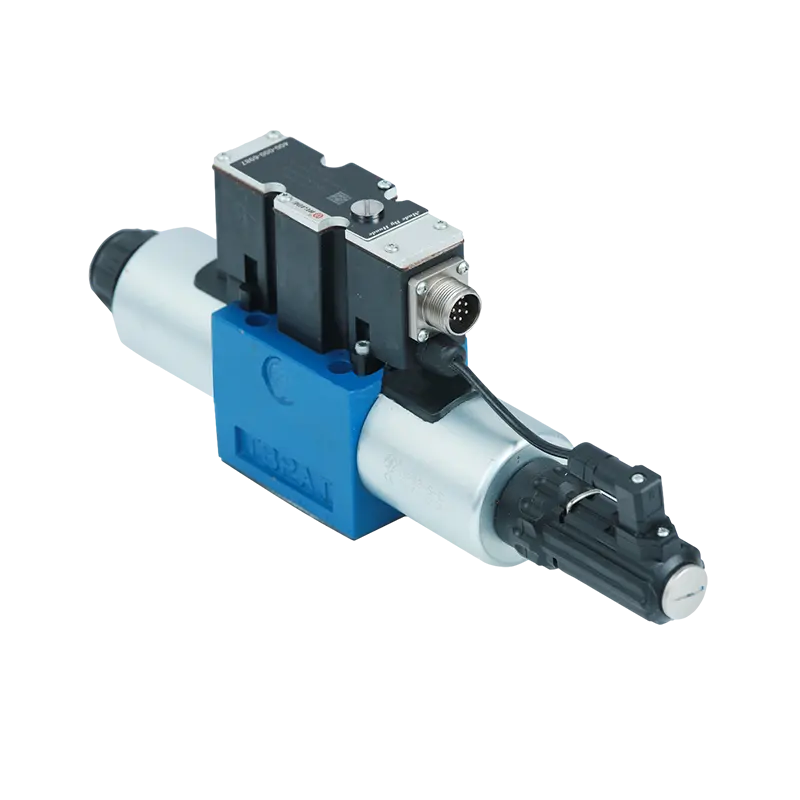

For proportional electronic control, the standard electromagnet symbol gains an additional arrow, or shows arrows on both the solenoid rectangle and the valve body. This indicates proportional response where coil current determines valve position continuously rather than simple on-off switching. Advanced closed-loop valves add a position sensor symbol (typically a rectangle opposite the electromagnet) connected by dashed feedback lines, representing LVDT or other displacement transducers providing real-time spindle position data.

Pressure Compensation: From Throttle Valve to Flow Control Valve

Here's where symbol reading becomes critical for system performance prediction. A basic throttle valve symbol shows only the diagonal adjustment arrow. But many applications need flow rate to remain constant regardless of load pressure variations. An excavator bucket extending should move at the same speed whether empty or full of gravel. A basic throttle valve fails this requirement because flow rate equals the discharge coefficient times area times the square root of pressure drop. If load pressure changes, pressure drop across the throttle changes, and flow rate varies.

The flow control valve solves this through pressure compensation. It adds a differential pressure regulator in series with the adjustable throttle. The regulator senses downstream pressure and automatically adjusts its own opening to maintain constant pressure drop across the main throttle orifice. Since pressure drop stays fixed, flow depends only on the adjusted orifice area.

The ISO symbol shows this by adding a small arrow directly on the flow line passing through the valve body, in addition to the diagonal adjustment arrow. That flow-line arrow is the universal marker for pressure compensation. You might also see detailed schematics showing the complete internal structure: an adjustable throttle element in series with a pressure-reducing valve, connected by a pilot line that feeds back load pressure.

Temperature compensation adds another layer. High-performance flow control valves incorporate thermal sensing elements (bimetallic strips or other temperature-responsive devices) that automatically adjust orifice area as oil viscosity changes with temperature. Symbols may show a thermometer marking near the adjustment arrow, or include explicit temperature sensor notation.

| Valve Type | ISO Symbol Features | Physical Behavior | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Orifice | Restriction lines only, no arrows | Flow varies with pressure and temperature | Pilot circuit damping, pressure gauge buffering |

| Adjustable Throttle | Diagonal adjustment arrow | Flow varies with load pressure and temperature | Simple speed adjustment, low-precision control |

| Pressure-Compensated Flow Control | Diagonal arrow plus flow-line arrow | Flow constant with load changes, varies with temperature | Machine tool feed drives, vehicle propulsion |

| Pressure and Temperature Compensated | Both arrows plus temperature indicator | Flow constant regardless of load or temperature | Precision injection molding, aerospace actuation |

Check-Throttle Valves: Reading Composite Symbols

Most practical hydraulic circuits need asymmetric control. You want the actuator to move slowly in one direction (the working stroke) but return quickly in the opposite direction. This requires combining a throttle with a check valve in what ISO 1219 calls a check-throttle valve or one-way throttle valve.

The symbol shows a parallel arrangement: the throttle restriction and the check valve sit side by side, usually enclosed in a dashed or solid rectangle indicating they're integrated into a single valve body. The check valve symbol consists of a small circle (representing the ball or poppet) pressed against a V-shaped seat. Understanding flow direction through this composite symbol requires careful attention to the check valve orientation.

Flow pushing against the ball toward the point of the V-shaped seat closes the check valve. The ball seals tightly against the seat, blocking flow through that path. All fluid must pass through the adjacent throttle restriction, creating the controlled, slow movement. Flow pushing the ball away from the seat opens the check valve. The ball lifts off, allowing free flow with minimal resistance. Most fluid bypasses the throttle, taking the low-resistance path through the check valve for rapid return motion.

The critical reading rule: the direction where the check valve blocks flow is the throttle direction. The direction where the check valve opens is the free-flow direction. New technicians often reverse this logic, thinking the check valve arrow shows the controlled direction. It shows the opposite - the uncontrolled, fast-return direction.

Many check valves include a spring behind the ball, shown as a zigzag line in the symbol. This spring creates a cracking pressure, typically between 0.5 and 3 bar, that must be overcome before the valve opens. This isn't negligible in system pressure calculations. That cracking pressure adds to the total system resistance and affects actuator force balance.

Circuit Architecture: Where Symbols Appear Matters More Than What They Look Like

The same check-throttle valve symbol placed in different positions within a hydraulic circuit creates radically different system behaviors. This is where symbol reading transcends simple component identification and becomes system-level analysis.

Meter-In Control Architecture

When the throttle valve symbol appears in the supply line leading into the actuator, you're looking at meter-in control. The check valve orientation allows free flow during retraction (the check opens) but forces supply flow through the throttle during extension. This limits the flow entering the cylinder, controlling extension speed.

Meter-in works acceptably for resistive loads where the load force opposes motion direction (like pushing a heavy object up a ramp). But it fails catastrophically for overrunning loads. Consider a hydraulic cylinder lowering a suspended weight. Gravity pulls the piston down faster than the pump supplies oil to the rod-end chamber. The extending chamber creates vacuum, pulling dissolved air out of solution. You get cavitation, noise, jerky motion, and ultimately loss of control. The load runs away.

Meter-in throttle valve symbols should immediately trigger a question: what happens if this load tries to pull the actuator? If the answer involves potential runaway, the circuit needs redesign.

Meter-Out Control Architecture

Placing the throttle valve symbol in the return line creates meter-out control. Now the check valve opens during extension (free flow in) but closes during retraction, forcing return oil through the throttle. The restricted exhaust creates backpressure in the retracting chamber. This backpressure acts like a hydraulic brake, creating resistance that opposes motion regardless of whether the load pushes or pulls.

Meter-out excels at load rigidity. Even with overrunning loads like suspended weights or vehicles descending slopes, the backpressure prevents runaway. The system maintains controlled speed in both motion directions. This explains why construction equipment and industrial lifts default to meter-out configurations.

But meter-out introduces a different hazard: pressure intensification. In differential cylinders where the rod-end area is smaller than the cap-end area, restricting the rod-end exhaust while pressurizing the cap end can generate rod-end pressures far exceeding pump supply pressure. The pressure multiplication ratio equals the area ratio. A 2-to-1 area ratio can produce rod-end pressures twice the supply pressure when the exhaust is blocked by the closed throttle valve. This can burst hoses or crack cylinder barrels. Reading the circuit requires calculating these pressure relationships, not just identifying symbols.

Bleed-Off Control Architecture

A third configuration places the throttle valve symbol in a branch line connecting the supply to tank, parallel to the main actuator path. This bleeds off a portion of pump flow, letting the remainder go to the actuator. Bleed-off control offers better energy efficiency because the pump only generates pressure needed for the load, not additional pressure to overcome throttle restriction. But speed stability is poor. Any load variation changes the flow split ratio, causing large speed fluctuations.

| Architecture | Symbol Location | Load Suitability | Energy Loss | Primary Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meter-In | Supply line to actuator | Resistive loads only | High (relief valve losses) | Cavitation and runaway with overrunning loads |

| Meter-Out | Return line from actuator | Resistive and overrunning loads | High (throttle pressure drop) | Pressure intensification causing component failure |

| Bleed-Off | Branch line to tank | Low precision applications | Lower (no throttle pressure drop) | Poor speed stability with load variation |

ANSI/ISA-5.1 Symbols in Process Control Systems

Moving from fluid power to process instrumentation, the throttle valve symbol language shifts dramatically. Process and Instrumentation Diagrams serve chemical plants, refineries, pharmaceutical facilities, and water treatment systems. Here, "throttle valve" is sometimes a colloquial term for any valve used in flow modulation service, but the standard terminology distinguishes between valve types by body design and actuation method.

Globe Valve as Throttling Device: The globe valve serves as the workhorse for throttling service in process systems. Its ISA 5.1 symbol shows the standard bow-tie shape (two opposing triangles meeting at their points) with a solid black circle at the center. That central dot represents the closure member moving perpendicular to flow direction, mimicking the physical reality of a globe valve where the plug travels vertically to progressively block the flow path.

Contrast this with a gate valve symbol (hollow bow-tie or bow-tie with a vertical line), used for on-off isolation service. Attempting to throttle with a gate valve causes severe turbulence and erosion at partial openings. Ball valves use a circle in the center of the bow-tie, indicating rotational closure action. While quarter-turn operation makes ball valves excellent for isolation, standard ball valves provide poor flow control linearity. V-notch ball valves adapt rotary motion for modulation, but even these rarely match globe valve performance for continuous throttling.

Manual Control Valves (HCV): When a manually-operated valve plays a critical role in process control rather than just equipment isolation, ISA 5.1 classifies it as a Hand Control Valve. The symbol may show a handwheel actuator atop the valve body, and the instrument tag will read HCV followed by a number (like HCV-201). This designation signals operators and maintenance staff that this valve's position has been calculated and set for specific process conditions. It shouldn't be adjusted casually or fully opened during routine operations.

The distinction matters. An ordinary manual valve might just carry a line number (like V-201). Seeing HCV tells you this valve's throttling position directly affects process variables like reactor temperature, column reflux ratio, or reactor pressure. Messing with an HCV without understanding the process consequences can trigger alarms, product quality deviations, or safety incidents.

Restriction Orifice (RO) and Flow Orifice (FO): Process piping also uses fixed throttling devices. The restriction orifice symbol appears as two short parallel lines perpendicular to the process line, sometimes annotated with RO or FO. Unlike the adjustable valves discussed earlier, an RO is a permanent installation: a precisely-drilled hole in a metal plate sandwiched between pipe flanges. Restriction orifices limit maximum flow in relief discharge lines, provide minimum flow recirculation for centrifugal pumps, or create intentional pressure drop for process requirements. They're sized during design and can't be adjusted without physically removing and replacing the orifice plate. Reading these symbols correctly means recognizing where the designer intentionally built in permanent flow restrictions.

Control Valve Assemblies: Fully automated control valves in ISA diagrams combine the valve body symbol with actuator and controller symbols. A pneumatic actuator appears as a mushroom-shaped diaphragm above the valve. An electric actuator shows as a motor symbol. The instrument tag often reads FCV (Flow Control Valve), PCV (Pressure Control Valve), or LCV (Level Control Valve) depending on the controlled variable.

The complexity increases when you see fail-safe indications. A spring shown in the actuator symbol indicates fail-closed (FC) or fail-open (FO) behavior. On air supply loss, the spring drives the valve to a predetermined safe position. Reading this correctly is essential for safety analysis. A throttle valve on a reactor feed line that fails open on instrument air loss could cause a runaway reaction. One that fails closed might cause vacuum damage to vessels from continuing withdrawal streams.

Common Symbol Reading Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

The precision required in reading throttle valve symbols leaves little room for assumptions. Several recurring errors plague even experienced technicians when they work across industries or switch between standard systems.

Key Mistakes to Watch For

- Confusing Automotive "Throttle" with Hydraulic Throttle: In automotive engineering, "throttle valve" specifically means the engine throttle body controlling air intake (butterfly valve symbols). An automotive technician reading a hydraulic schematic might see "throttle valve" and expect electronic throttle control logic, missing that the symbol represents passive flow restriction in fluid transmission.

- Misreading Single-Direction Symbols: The most dangerous error involves reversing the logic of check-throttle valves. Seeing the check valve arrow, technicians assume it shows the controlled direction. This inverts the circuit's actual behavior. The check valve arrow shows the free-flow direction. The throttled direction is where the check valve blocks flow, forcing fluid through the restriction.

- Ignoring Symbol Details in CAD Libraries: Modern engineering relies heavily on CAD software with pre-built symbol libraries. Unfortunately, many libraries contain symbols that don't fully comply with current standards. A common problem is failing to distinguish between viscosity-dependent (curved lines) and viscosity-independent (angular lines) throttle symbols.

- Overlooking Pressure Rating and Flow Direction: Some symbols include embedded information about pressure rating through line weight or annotation. Misreading flow direction reverses your understanding of whether a valve is in meter-in or meter-out position.

Best practice requires maintaining custom symbol libraries that enforce standards compliance and adding a comprehensive symbol legend sheet to every drawing package. The legend should explicitly state which standard governs which drawing types and show example symbols with text descriptions.

Semiconductor and Specialty Applications

Beyond traditional hydraulic systems and process plants, throttle valve symbols appear in highly specialized contexts where terminology shifts again. Semiconductor manufacturing equipment uses precisely-controlled gas flow for chemical vapor deposition (CVD), physical vapor deposition (PVD), and etch processes. These systems employ mass flow controllers (MFCs) that integrate flow sensors, control electronics, and throttling valves into single instruments.

An MFC symbol in equipment schematics often shows as a rectangle containing both a flow transmitter symbol (circle with FT) and a control valve symbol. While the internal throttling valve is physically similar to other needle valves, engineers treat MFCs as intelligent instruments rather than simple valves. The distinction matters: you don't manually adjust an MFC throttle. You send a setpoint to its controller, which automatically positions the valve to achieve the target mass flow rate.

Semiconductor process tools also distinguish between upstream and downstream control. An upstream mass flow controller maintains constant flow regardless of downstream pressure variations. A downstream throttle valve (often a butterfly valve on the vacuum pump exhaust) controls chamber pressure. The terminology "throttle valve" in vacuum systems often refers specifically to pressure control valves rather than flow control devices. Context determines meaning.

Conclusion: Symbols as Engineering Language

Throttle valve symbols function as vocabulary in the language of engineering drawings. Like any language, precise meaning depends on context, grammar (standard systems), and syntax (circuit architecture). A single geometric symbol - two angled lines pinching a flow path - carries information about fluid dynamics, control strategy, load characteristics, and potential failure modes.

Reading these symbols well requires moving beyond simple pattern recognition. You need to understand the physics behind the geometry: how Bernoulli's equation relates to symbol shape, what Reynolds number tells you about viscosity sensitivity, and how pressure compensation mechanisms appear in symbol notation. You must grasp the standard systems: when to expect ISO 1219 functional abstraction versus ANSI/ISA-5.1 equipment identification. And you need system-level thinking to interpret how symbol position within circuit architecture determines whether a load can run away or pressure can intensify to destructive levels.

For engineers designing new systems, symbols must accurately communicate intent to fabricators, commissioning technicians, and maintenance staff years into the future. For technicians troubleshooting problems, correctly reading symbols means identifying whether control strategy matches load characteristics and whether actual valve installations follow the design.

The throttle valve symbol proves that effective engineering communication depends not on elaborate graphics but on precise, standardized notation that encodes complex physical relationships in simple geometric forms. Understanding this language transforms blueprints from mere paper into roadmaps revealing how systems work, where they might fail, and how to make them better.