In modern hydraulic systems, controlling how fast fluid moves through the circuit determines how quickly your machinery operates. When you see a hydraulic cylinder extending slowly or rapidly, that speed difference comes from one critical component: the flow control valve. Understanding the different hydraulic flow control valve types available helps engineers select the right solution for their specific application, whether it's a mobile excavator that needs consistent bucket speed under varying loads or a precision manufacturing system requiring synchronized multi-cylinder movement.

The fundamental principle behind all hydraulic flow control valve types starts with a simple physics equation. Flow rate through an orifice follows the relationship:

Where flow (Q) depends on the orifice area (A) and the pressure difference across it. This square-root relationship creates a challenge: when load pressure changes, flow changes too, even if you haven't touched the valve setting. Different valve types solve this problem in different ways, which is why understanding their operating principles matters for system design.

Basic Non-Compensated Flow Control Valves

The simplest hydraulic flow control valve types work by creating a restriction in the flow path. These valves change the orifice area to control flow, but they don't compensate for pressure variations. While this makes them less precise than advanced designs, their simplicity and low cost make them suitable for applications where load pressure remains relatively constant or speed precision isn't critical.

Needle Valves and Their Precision Advantage

Needle valves feature a tapered, needle-shaped element that moves into a conical seat. The fine thread on the adjustment stem allows extremely small changes in orifice opening. When you turn the adjustment knob one full rotation, the needle might move only 0.5mm, giving you precise control over very small flow rates. This makes needle valves particularly valuable in pilot circuits, gauge damping applications, and instrumentation lines where flow rates might be as low as 0.1 liters per minute.

The conical geometry also provides nearly linear flow characteristics across much of the adjustment range. However, needle valves have limitations. The small orifice size means they're prone to clogging if fluid cleanliness drops below ISO 4406 18/16/13 levels. Additionally, because they lack pressure compensation, a needle valve set to deliver 2 liters per minute at 50 bar load pressure might deliver 2.8 liters per minute if load drops to 20 bar. This 40% speed variation makes them unsuitable as the primary speed control in systems with variable loads.

Globe Valves in Hydraulic Service

Globe valves feature an internal flow path that forces fluid to change direction twice, creating a Z-shaped flow pattern through the valve body. The disk-shaped or plug-shaped closure element sits perpendicular to the flow stream. This design creates higher pressure drop compared to straight-through valves, but provides good throttling characteristics.

In hydraulic applications, globe valves typically handle larger flow rates than needle valves—usually from 5 to 100 liters per minute. The adjustment is less precise than needle valves, but the more robust construction handles particulate contamination better. The seat and disk undergo less erosion damage because the geometry distributes forces more evenly. However, like all non-compensated throttle valves, globe valves suffer from the same load-sensitivity issue. A cylinder pushing a 10-ton load will move slower than when pushing 5 tons, even with identical valve settings.

V-Notch Ball Valves for Throttling

Standard ball valves serve primarily as on-off isolation devices, but the V-notch ball valve represents an evolution specifically for flow control. Instead of a circular port, the ball contains a V-shaped cutout. As the ball rotates, the V-notch progressively increases the flow area, providing an equal-percentage flow characteristic. This means each degree of rotation produces a flow change proportional to the current flow, rather than a fixed increment.

The V-notch design suits applications requiring large flow capacity with reasonable throttling capability. A 2-inch V-ball can handle 200+ liters per minute at full opening while still providing controllable reduction down to 20% of maximum. The hard metal-to-metal or metal-to-elastomer sealing provides tight shutoff. However, these valves share the pressure sensitivity limitation—flow varies with the square root of pressure difference, making them unsuitable for precision speed control under variable loading.

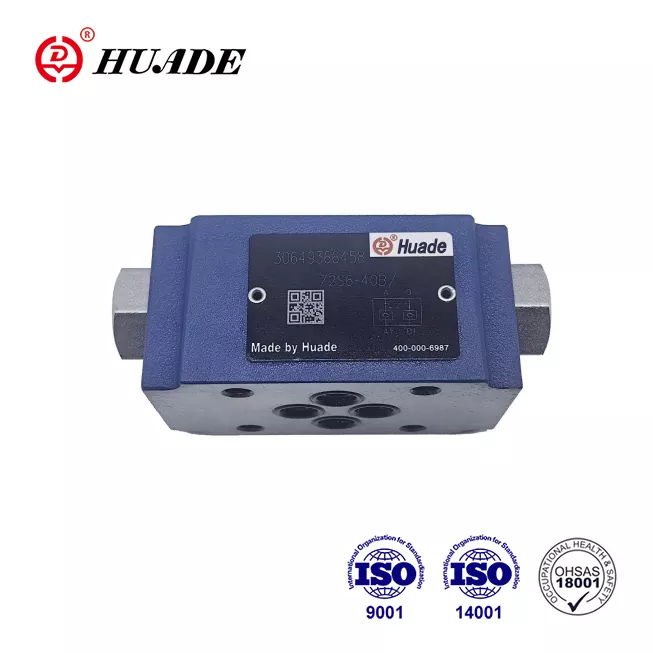

Pressure-Compensated Flow Control Valves

When hydraulic systems demand consistent actuator speed regardless of load changes, pressure-compensated flow control valves become necessary. These valves solve the fundamental problem inherent in simple throttling: they maintain constant pressure drop across the metering orifice by automatically adjusting a secondary restriction element. This innovation transforms an inherently pressure-sensitive device into a true flow controller.

The key to pressure compensation lies in adding a spring-loaded compensator spool in series with the main throttling orifice. This compensator senses pressure both upstream and downstream of the metering section. When load pressure increases, the compensator automatically opens slightly, reducing its own restriction to keep the pressure drop across the main orifice constant. Conversely, when load pressure drops, the compensator closes partially to prevent flow increase.

Two-Way Pressure Compensated Valves

Two-way pressure-compensated flow control valves connect in series with the actuator circuit. The valve consists of the main adjustable orifice and the compensator element arranged so all controlled flow passes through both restrictions. The compensator spring typically sets a fixed differential pressure of 5 to 10 bar across the main orifice.

How it responds to load changes

Imagine you've set the valve to deliver 10 liters per minute to a cylinder. Initially, system pressure is 100 bar and load pressure is 80 bar. The compensator adjusts itself so pressure between the compensator and main orifice is exactly 90 bar (80 + 10 bar spring setting).

Now the load increases, raising cylinder pressure to 90 bar. Without compensation, flow would drop. But the compensator immediately senses the downstream pressure rise and opens wider. This reduces the compensator's own pressure drop, ensuring the main orifice still sees exactly 10 bar across it. Flow stays at 10 liters per minute.

The limitation of two-way compensated valves shows up in energy efficiency. When the pump delivers more flow than the valve passes, the excess must return to tank through the system relief valve. This excess flow crosses the relief valve at full system pressure, converting hydraulic power directly into heat.

Three-Way Pressure Compensated Valves

Three-way pressure-compensated valves add a third port that bypasses excess pump flow directly to tank. Instead of forcing excess flow over the high-pressure relief valve, the three-way valve's compensator diverts it through the bypass port at only slightly above load pressure. This dramatically reduces energy waste.

The compensator in a three-way valve performs dual functions. First, it maintains constant differential across the metering orifice just like in a two-way valve. Second, when pump flow exceeds the set flow rate, the compensator directs the surplus through the bypass port. The key difference is the pressure at which this bypass occurs. The diverted flow crosses the compensator at load pressure plus the compensator spring setting (typically 10 bar), not at relief valve pressure (which might be 200 bar).

Pre-Compensation Versus Post-Compensation in Multi-Actuator Systems

When multiple hydraulic flow control valves connect to a single pump, the position of the pressure compensator relative to the main directional valve spool becomes critical. This seemingly minor design detail determines whether the system maintains smooth coordinated motion when pump flow becomes insufficient for all actuators.

In pre-compensated systems, the compensator sits upstream of the directional control spool. Each valve section compensates its own flow independently. This works perfectly when pump capacity exceeds total demand. However, when you simultaneously operate multiple functions and total demand exceeds pump flow, pre-compensated valves exhibit flow saturation. The actuator with the lowest load pressure receives full flow while high-load actuators slow down or stop entirely.

Post-compensated valves (also called Load Sensing Independent Metering or LUDV systems) place the compensator downstream of the directional valve. When pump flow saturates, all compensators reduce their openings proportionally. This flow-sharing behavior means all actuators slow down together while maintaining their speed ratios. For mobile machinery requiring coordinated multi-axis control, post-compensation is essentially mandatory.

| Valve Type | Excess Flow Handling | Energy Efficiency | Typical Applications | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Way Compensated | Returns through relief valve | Low (high heat generation) | Variable displacement pump systems | Not suitable for continuous operation with fixed pumps |

| Three-Way Compensated | Bypasses to tank at load pressure | Medium (reduced heat) | Fixed pump systems, continuous duty | Typically meter-in only |

| Pre-Compensated | Varies by valve design | Medium | Single actuator or sequential operation | Flow saturation causes uneven actuator response |

| Post-Compensated (LUDV) | Varies by valve design | Medium to High | Mobile equipment, multi-actuator coordination | Higher cost and complexity |

Flow Divider and Combiner Valves

When a hydraulic system needs two or more actuators to move at exactly the same speed, simple parallel connections don't work. Fluid naturally follows the path of least resistance, meaning the actuator with the lowest load receives all the flow while others stall. Flow divider valves solve this problem by mechanically or hydraulically forcing flow to split in fixed proportions regardless of individual load pressures.

Spool-Type Flow Dividers

Spool-type flow dividers use pressure sensing and variable throttling to balance flow between outlets. Inside the valve body, each outlet has a fixed orifice that all flow must pass through. After these fixed orifices, the pressure in each branch acts on opposite ends of a balanced spool. If one branch starts receiving more flow, pressure drop across its fixed orifice increases, creating an imbalance that shifts the spool. This movement restricts the high-flow side while opening the low-flow side until flows equalize.

The dividing accuracy of quality spool-type valves reaches plus or minus 2.5 to 5 percent of total flow. This precision makes spool dividers suitable for synchronized lifting platforms, dual-cylinder presses, and positioning systems where the cylinders must arrive at end positions within millimeters of each other. However, the weakness of spool-type dividers is their sensitivity to contamination. Particles lodging in clearances cause the spool to stick, destroying synchronization accuracy.

Gear-Type Flow Dividers

Gear-type flow dividers take a fundamentally different approach using positive displacement principles. The valve consists of two or more gear sections (similar to gear motors) mounted on a common shaft. Incoming flow enters a common inlet and drives all gear sets. Because the shaft mechanically couples all sections, they must rotate at identical speeds. Each gear section displaces a volume proportional to its displacement setting, forcing flow division in exact proportion to the gear ratios.

Gear dividers excel in efficiency and ruggedness, tolerating contamination levels up to ISO 4406 20/18/15. They are ideal for continuous-duty applications like synchronizing multiple hydraulic motors in conveyor drives. However, they have a dangerous characteristic called pressure intensification. If one outlet becomes blocked, the blocked section acts as a pump, generating extremely high pressure. Every outlet of a gear divider must have a pressure relief valve.

| Characteristic | Spool-Type Divider | Gear-Type Divider |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Principle | Pressure sensing with variable throttling | Positive displacement with mechanical coupling |

| Dividing Accuracy | ±2.5% to ±5% | ±5% to ±10% |

| Contamination Tolerance | ISO 4406 17/15/12 or better | ISO 4406 20/18/15 acceptable |

| Efficiency | 75-85% (heat generation) | 92-98% (minimal energy loss) |

| Critical Safety Requirement | None beyond normal system protection | Mandatory outlet relief valves to prevent intensification |

Cartridge and Logic Valves for High Flow Applications

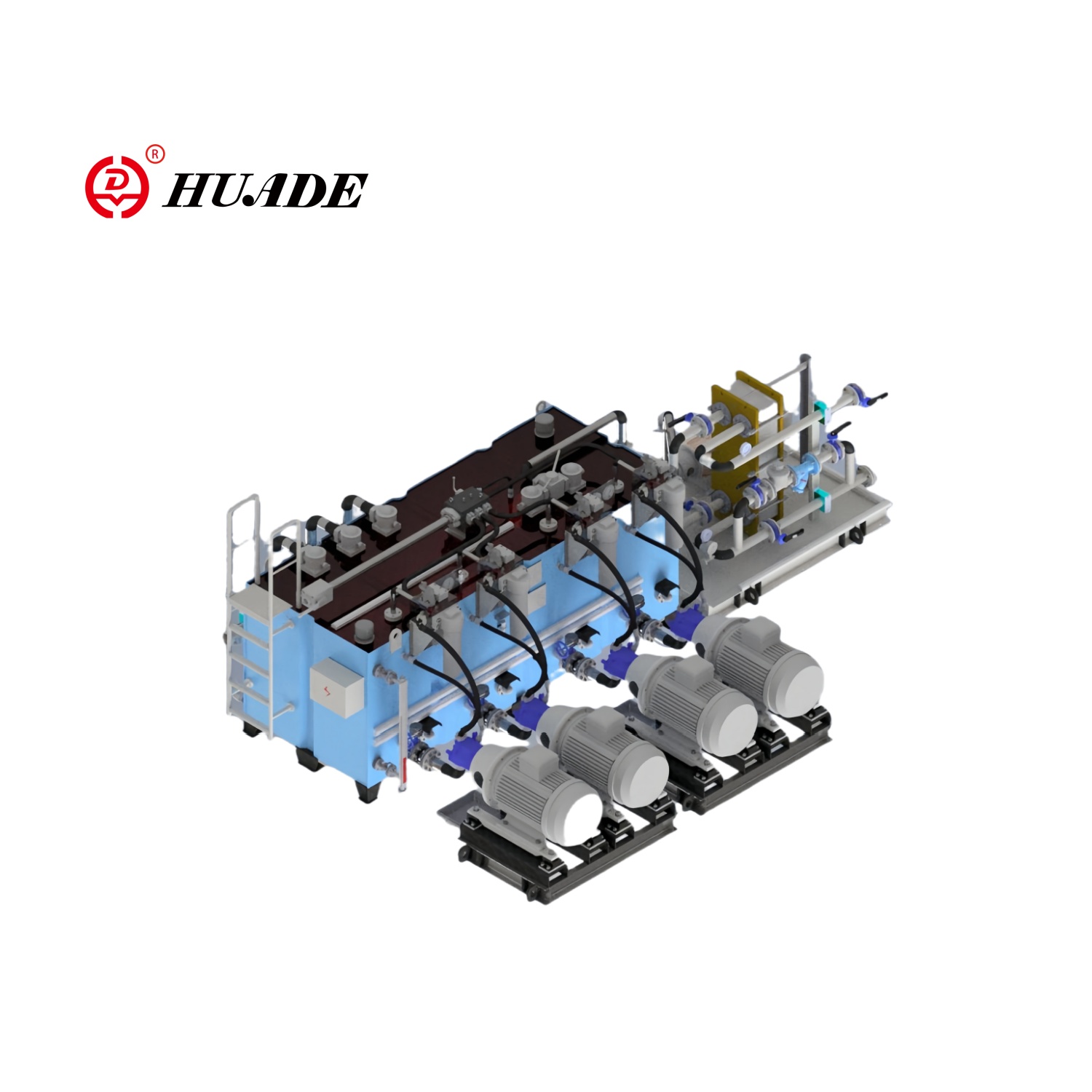

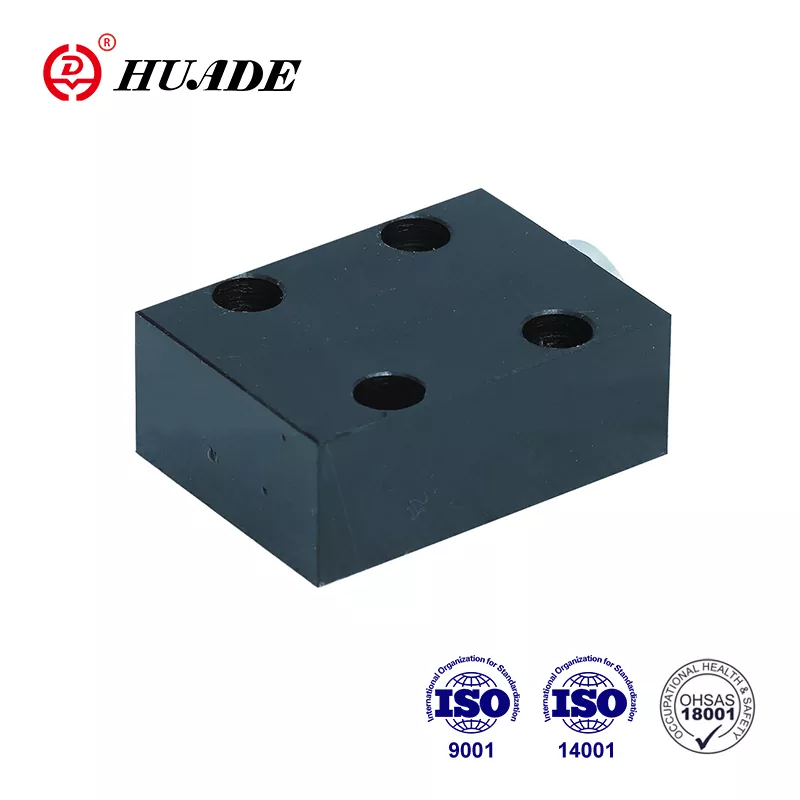

As hydraulic systems scale up in power, traditional spool valves become physically too large. Cartridge-style flow control valves solve this by separating the valve function into a small logic element inserted into a drilled manifold block. This approach dramatically reduces size and weight while enabling much higher flow capacity in a compact package.

Two-Way Cartridge Logic Elements

The basic two-way cartridge valve consists of a poppet element sitting in a threaded or slip-in housing. Unlike spool valves that use overlapping lands for control, cartridge valves use seat-type closure. Flow control happens by restricting how far the poppet lifts off its seat. A pilot valve controls pressure in the top chamber. By modulating this pilot pressure, you control the force balance on the poppet, which determines the opening size.

The advantages are significant. First, flow capacity scales dramatically. Second, the zero-leakage seat design eliminates the internal leakage inherent in spool valves. Third, a single cartridge body becomes a directional valve, pressure valve, or flow valve simply by changing the pilot cover assembly mounted on top.

Proportional and Servo Flow Control

When hydraulic systems integrate with PLCs or CNC systems, mechanical adjustment gives way to electronic command signals. Proportional and servo valves translate electrical inputs into precise flow outputs.

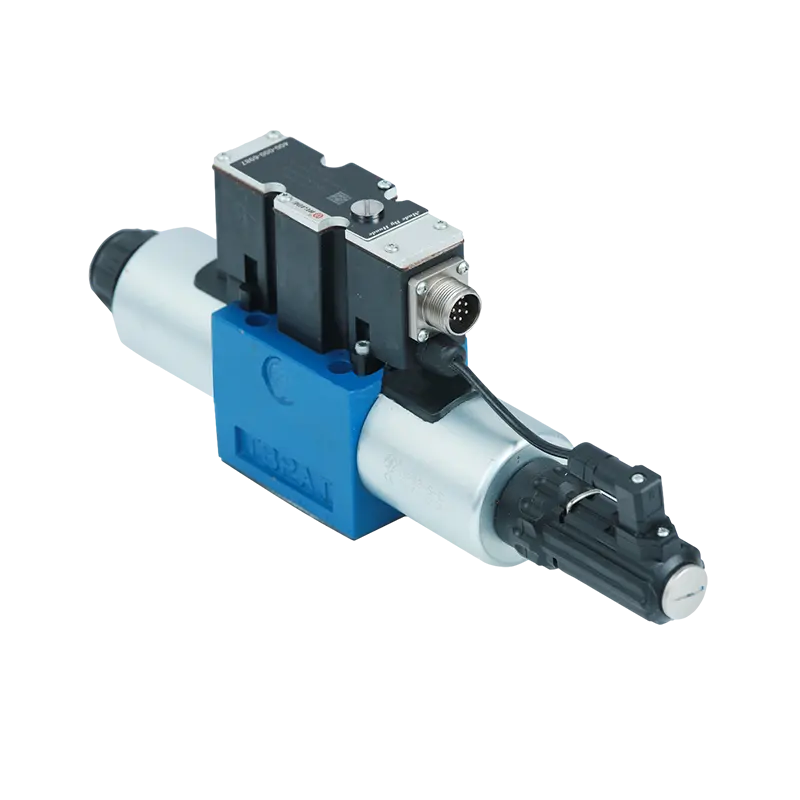

Proportional Flow Control Valves

Proportional valves replace the manual adjustment screw with a proportional solenoid. Instead of turning a knob, the control system sends a current signal that generates electromagnetic force to position the valve spool. Modern valves use pulse-width modulation (PWM) drive signals with superimposed dither frequencies. This high-frequency vibration keeps the pilot spool in constant micro-motion, breaking static friction and reducing hysteresis to 1-2% or less.

Servo Valves for High-Dynamic Applications

Servo valves represent the pinnacle of hydraulic control precision. Instead of using a proportional solenoid acting directly on the main spool, servo valves employ a two-stage design with a torque motor. The low moving mass and minimal mechanical friction give servo valves exceptional dynamic response. Frequency response commonly exceeds 100 Hz, meaning a servo valve can accurately reproduce command signals changing 100 times per second.

| Parameter | Proportional Valve | Servo Valve |

|---|---|---|

| Actuator Type | Proportional solenoid (direct force) | Torque motor with hydraulic amplification |

| Frequency Response | 10-50 Hz (-3dB point) | 100-200+ Hz (-3dB point) |

| Hysteresis | 1-2% (with dither); <0.5% (with LVDT) | <0.3% typical |

| Contamination Sensitivity | Moderate (requires ISO 4406 18/16/13) | Extreme (requires ISO 4406 14/12/09) |

| Cost (relative) | Moderate | 3-5x higher than proportional |

Temperature Effects and Viscosity Considerations

Hydraulic flow control valve types respond differently to temperature changes because fluid viscosity varies dramatically with temperature. Mineral-based hydraulic oils typically show viscosity dropping by half for every 25-degree Celsius temperature increase. For simple throttling valves, this means equipment might run dangerously fast after warmup.

Sharp-edged orifice designs counteract this problem. When fluid passes through an orifice with a sharp entrance edge, flow instantly transitions to a turbulent regime. In turbulent flow, the discharge coefficient becomes essentially independent of viscosity. This is why pressure-compensated flow control valves universally employ sharp-edged orifices in their metering sections.

Selection Criteria for Different Applications

Choosing among the various hydraulic flow control valve types requires analyzing load characteristics, precision requirements, duty cycle, and energy efficiency needs.

Load Type Assessment

Resistive loads work fine with simple throttle valves. Overrunning loads (like lowering a heavy weight) require pressure-compensated valves combined with counterbalance valves. For applications involving highly variable loads, pressure compensation becomes mandatory. Only pressure-compensated valves can achieve consistent lift speed whether a pallet weighs 200kg or 800kg.

Energy Efficiency Considerations

Calculating the Cost of Inefficiency

Energy costs increasingly drive valve selection. Consider a 50-horsepower hydraulic system running two shifts daily. Every 10% efficiency improvement saves roughly $3000-4000 annually in electricity costs.

- Intermittent operation: Simple two-way pressure-compensated valves work acceptably.

- Medium-duty: Use three-way pressure-compensated valves to reduce heat generation.

- Continuous duty: Demand load-sensing systems where pump displacement automatically adjusts to system demand.

Conclusion

The range of hydraulic flow control valve types reflects decades of engineering evolution addressing different application requirements. Simple needle valves and throttle valves suit low-cost applications where load stability exists. Pressure-compensated valves deliver consistent actuator speeds under variable loads. Flow divider valves solve multi-actuator synchronization challenges.

Understanding these hydraulic flow control valve types and their operating principles allows engineers to specify systems that meet performance requirements without over-engineering. Successful hydraulic system design matches valve characteristics to actual operating conditions, accounting for load variations, required precision, duty cycle, contamination environment, and total cost of ownership rather than just purchase price.