In modern industrial systems, controlling fluid flow with precision is not just about opening or closing a pipe. The choice of valve type directly impacts system efficiency, operational safety, and long-term maintenance costs. Whether you're designing a chemical processing line, a steam distribution network, or a hydraulic control system, understanding the fundamental differences between flow valve types is the foundation of sound engineering decisions.

Flow control valves serve as the final control element in process loops, translating electronic signals or manual commands into physical changes in flow rate, pressure, or direction. The global valve industry recognizes dozens of distinct designs, but they can be systematically categorized based on their internal mechanism, flow characteristics, and intended service. This guide breaks down the major flow valve types according to engineering principles rather than marketing classifications.

Understanding Flow Control Valve Classifications

The engineering community divides flow valve types into two fundamental categories based on how the closure element moves: linear motion valves and rotary motion valves. This distinction is not merely academic. It determines the valve's torque requirements, maintenance accessibility, flow capacity coefficient (Cv), and suitability for throttling versus on-off service.

Linear motion valves move their closure element in a straight line, either parallel or perpendicular to the flow path. This group includes gate valves, globe valves, diaphragm valves, and needle valves. They typically offer superior shutoff capability and precise flow modulation but often create higher pressure drops due to their internal geometry.

Rotary motion valves, which include ball valves, butterfly valves, and plug valves, operate through a 90-degree quarter-turn rotation. These designs generally provide larger flow capacity (higher Cv values) in the same pipe size, require less installation space, and deliver faster operation. However, their throttling performance varies significantly depending on the specific design.

Beyond these two primary groups, specialized flow valve types serve specific functions. Check valves prevent backflow using the fluid's own kinetic energy. Pressure control valves (pressure reducing valves) maintain downstream pressure without external power. Understanding these distinctions helps engineers match valve capabilities to system requirements rather than relying on generic specifications.

Linear Motion Valve Types

Linear motion valves dominate applications requiring tight shutoff or precise flow modulation. Their closure element travels along the valve stem axis, creating a mechanical advantage that delivers high seating forces.

Gate Valves

``` [Image of gate valve internal mechanism] ```Gate valves are the industry standard for isolation service in high-pressure piping systems. The closure element, called a gate or wedge, slides vertically into the flow stream, cutting through the fluid like a knife. When fully open, the gate retracts completely into the bonnet, creating a straight-through flow path with minimal resistance.

The gate valve design comes in several configurations. Solid wedge gates offer maximum structural strength but can bind under thermal cycling. Flexible wedge gates incorporate a connecting rib between two sealing surfaces, allowing slight deformation to compensate for seat wear and thermal expansion. This flexibility prevents the jamming phenomenon common in rigid designs subjected to temperature fluctuations.

Engineering Note: Gate valves follow API 600 standards for industrial applications and API 6D for pipeline service. One critical specification difference is that API 6D requires full bore design to allow passage of pipeline pigs used for cleaning and inspection. Attempting to throttle flow with a partially open gate valve is an engineering mistake. The turbulent flow around the partially exposed gate edge creates severe erosion known as wire drawing, which rapidly destroys the seating surfaces. Gate valves are strictly for fully open or fully closed service.

Globe Valves

Globe valves represent the workhorse of flow modulation across process industries. Unlike the straight-through path of a gate valve, fluid entering a globe valve must change direction twice, following an S-shaped path through a horizontal seat opening. A plug-shaped disc moves perpendicular to the seat, controlling flow area with precision.

This tortuous flow path creates substantial pressure drop, which is both a disadvantage and an advantage. The high head loss makes globe valves inefficient for applications where pressure conservation matters. However, this same characteristic makes them excellent throttling devices. The relationship between stem position and flow rate is nearly linear, allowing predictable control across a wide range.

Globe valve trim (the replaceable internal components) can be customized to achieve different inherent flow characteristics. Linear trim provides proportional flow change per unit of stem travel. Equal percentage trim, where flow changes by a constant percentage for equal stem increments, compensates for system pressure drop variations. This modular design, specified in IEC 60534 standards, allows engineers to optimize control performance without changing the valve body.

The rangeability of standard globe valves typically reaches 50:1, meaning they can effectively control flow from 2% to 100% of maximum capacity. High-performance designs extend this to 100:1 or beyond, making them suitable for processes with extreme load swings such as steam desuperheating stations.

Diaphragm Valves

Diaphragm valves physically separate the actuating mechanism from the process fluid using a flexible membrane. This barrier makes them uniquely suited for corrosive, abrasive, and sterile applications where contamination from packing leakage or stem corrosion is unacceptable.

Two main configurations exist. Weir-type diaphragm valves feature a raised contour in the flow path. The diaphragm presses against this weir to achieve shutoff, using a shorter stroke that extends diaphragm life. Straight-through diaphragm valves have a smooth, unobstructed bore that minimizes pressure drop and allows complete drainage. This design is critical for slurry service and sanitary applications where product must not accumulate in dead zones.

In biopharmaceutical manufacturing, diaphragm valves dominate because they meet ASME BPE standards for bioprocessing equipment. The internal surface finish, measured in microinches Ra (roughness average), must not exceed 20 microinches to prevent biofilm formation. Electro-polished surfaces reaching Ra values below 10 microinches are standard in high-purity applications. The flexible diaphragm eliminates the crevices and stagnant zones found in traditional stem-packing designs, making clean-in-place (CIP) and sterilize-in-place (SIP) procedures effective.

The diaphragm material itself becomes a critical selection factor. EPDM rubber suits water and steam service up to 280°F. PTFE-faced diaphragms handle aggressive chemicals but have lower temperature limits around 400°F. For pharmaceutical applications, FDA-compliant materials with full traceability are mandatory.

Needle Valves

``` [Image of needle valve structure] ```Needle valves are precision instruments for low-flow control. They essentially function as miniature globe valves, using a long, tapered needle that fits into a closely matched seat. The fine-pitch threads on the valve stem provide an exceptionally high turn-to-lift ratio, meaning many handle rotations are required to move the needle through its full travel.

This mechanical reduction translates rotational input into minute linear motion, enabling precise flow adjustment. In instrumentation systems, needle valves serve as root valves protecting pressure gauges and as bleed valves for hydraulic test points. Their ability to crack open just slightly, creating a controlled leak path for pressure relief or sample extraction, makes them irreplaceable in analytical systems.

Needle valves are not designed for large volumetric flow. Their small orifice and high flow resistance limit capacity. The engineering value lies in metering small quantities with repeatable accuracy. In chemical dosing systems where a 0.1 GPM adjustment matters, needle valves provide the resolution that larger valves cannot achieve.

Rotary Motion Valve Types

Rotary valves revolutionized flow control by reducing actuation from multi-turn operation to a simple quarter-turn motion. This speed advantage, combined with compact actuator requirements, drives their adoption in automated systems.

Ball Valves

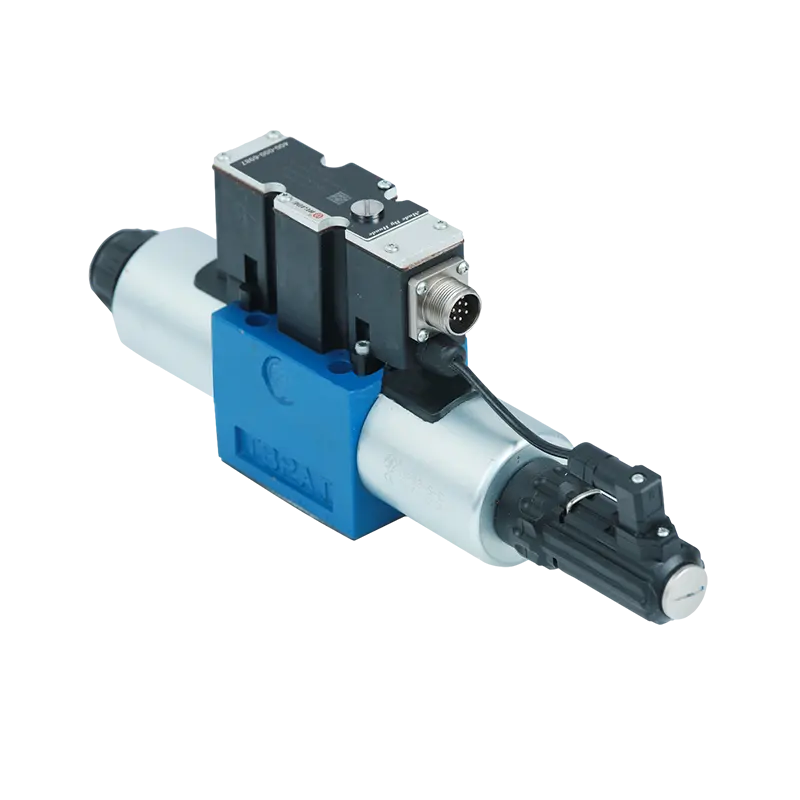

``` [Image of ball valve internal components] ```Ball valves use a spherical closure element with a cylindrical bore drilled through its center. Rotating the ball 90 degrees aligns or misaligns this bore with the pipeline, achieving full flow or complete shutoff. The seating mechanism differs fundamentally based on valve class.

Floating ball designs allow the ball to move slightly along its axis. Upstream pressure pushes the ball against the downstream seat, creating a pressure-assisted seal. This elegant simplicity makes floating ball valves cost-effective for low to medium pressure applications. However, as pressure increases, the seating force on the downstream seat grows proportionally, eventually causing excessive wear and high operating torque. Floating ball valves rarely exceed Class 600 ratings or 6-inch diameter.

Trunnion-mounted ball valves solve the pressure-force problem by mechanically supporting the ball with bearings top and bottom. The ball cannot move axially. Instead, spring-loaded seats move toward the ball surface. This reversal means higher pressure does not increase torque, making trunnion designs the standard for high-pressure service exceeding 1000 psi and large diameters above 8 inches. API 6D pipeline ball valves exclusively use trunnion mounting.

Standard ball valves exhibit a modified equal percentage flow characteristic. As the ball rotates from closed position, flow increases slowly at first, then accelerates rapidly near full open. This creates control challenges in the mid-range. V-port ball valves address this by machining a V-shaped contour into the ball opening. This geometric modification produces a nearly linear flow characteristic, transforming the ball valve from an isolation device into a capable control valve with rangeability exceeding 300:1.

Butterfly Valves

Butterfly valves achieve flow control through a circular disc rotating on a central shaft. When closed, the disc sits perpendicular to flow. At 90 degrees rotation, the disc aligns with flow direction, offering minimal obstruction. The elegance lies in simplicity—butterfly valves have fewer parts than almost any other valve type, translating to lower cost and weight.

Three design generations exist, each solving limitations of its predecessor. Concentric (zero offset) butterfly valves place the stem axis, disc center, and body centerline at the same point. The disc seals by pressing into a resilient elastomer liner. This design suits low-pressure HVAC and water distribution where a small amount of leakage is tolerable and operating temperatures stay below 200°F.

Double offset (high performance) butterfly valves shift the stem axis away from both the disc centerline and pipe centerline. This creates a cam action during opening, causing the disc to immediately lift away from the seat. Friction and wear reduce dramatically, extending service life and enabling metal seating for higher temperature applications up to 800°F.

Triple offset butterfly valves (TOBVs) add a third geometric offset by angling the seat cone axis relative to the pipe axis. This produces a right-angle metal-to-metal seal that only contacts at the final degrees of closure. The result is true zero-leakage shutoff meeting API 598 standards, fire-safe design per API 607, and bidirectional capability. TOBVs are gradually replacing gate valves in pipeline applications where their 75% weight reduction and lower actuation torque deliver significant system cost savings, particularly in diameters above 24 inches.

The flow characteristic of butterfly valves is highly non-linear. A concentric butterfly valve delivers 75% of maximum flow at just 60 degrees open. This "quick opening" characteristic limits their use in modulating control unless paired with sophisticated positioners that linearize the response.

Plug Valves

Plug valves use a cylindrical or tapered plug with a bored passage. Rotating the plug 90 degrees aligns or blocks the flow path. Compared to ball valves, plug valves offer a much larger sealing contact area, making them more tolerant of dirty fluids containing suspended solids.

Lubricated plug valves inject sealant grease under pressure into grooves machined in the plug body. This lubricant serves two functions: it provides the sealing interface and reduces friction. Regular relubrication is mandatory, making these valves higher maintenance. The advantage is their ability to handle abrasive slurries that would destroy a ball valve's polished seats.

Non-lubricated plug valves use elastomer sleeves or proprietary coatings to achieve sealing without injected lubricant. While this reduces maintenance, it limits temperature range and chemical compatibility. The trade-off between sealing mechanism and operational requirements drives the selection between lubricated and non-lubricated designs.

Specialized Flow Valve Types

Certain flow control requirements cannot be met by general-purpose valves. Specialized designs address unique functional needs.

Check Valves

Check valves prevent reverse flow using only the fluid's kinetic energy—no external actuation is required. When flow moves in the intended direction, pressure opens the valve. When flow stops or reverses, the closure element returns to its seat either by gravity, spring force, or reverse pressure.

Swing check valves use a hinged disc that swings open with forward flow. They create minimal pressure drop when fully open, making them popular in large pump discharge lines. The limitation is response time. In systems with rapid flow reversal, the disc may not close before significant backflow occurs. This delay can generate destructive water hammer when the disc finally slams shut against reverse flow momentum.

Lift check valves function like globe valves without the stem. The disc lifts vertically off its seat when forward pressure exceeds the spring force. They provide tight shutoff and fast response but create higher pressure drop due to the globe-style flow path. Lift checks are preferred in high-pressure steam service where leakage tolerance is zero.

Dual-plate wafer check valves split the disc into two semicircular plates spring-loaded closed. This design is exceptionally compact, installing between pipe flanges in the space of a single gasket. The spring closure provides rapid response, minimizing water hammer risk. The trade-off is slightly higher pressure drop compared to swing checks and limited repairability—most wafer checks are replaced rather than rebuilt.

API 594 and ISO 5208 define performance testing for check valves. A critical specification is the closing flow velocity—the minimum forward flow required to hold the valve open. If system velocity drops below this threshold, the valve begins to flutter, creating vibration and accelerating wear.

Pressure Control Valves

Pressure reducing valves (PRVs) maintain constant downstream pressure regardless of upstream pressure variations or flow rate changes. They operate entirely self-contained, deriving power from the process fluid itself, requiring no electricity or instrument air.

Direct-operated PRVs use a diaphragm sensing downstream pressure and a spring providing the setpoint force. When downstream pressure rises above setpoint, the diaphragm lifts against the spring, closing the valve plug and reducing flow. When pressure drops, the spring pushes the diaphragm down, opening the plug. This simple mechanism works reliably but exhibits "droop"—a gradual reduction in downstream pressure as flow rate increases, typically 10-15% from no-flow to maximum flow conditions.

Pilot-operated PRVs overcome the droop limitation through hydraulic amplification. A small pilot valve senses downstream pressure and controls the pressure in a chamber above the main valve diaphragm. The main valve acts as a power amplifier, following the pilot's signal with minimal droop, typically under 2%. This configuration handles much larger flow capacities while maintaining tight pressure control, making pilot-operated designs standard for natural gas distribution and municipal water supply.

The critical sizing parameter for PRVs is the flow coefficient (Cv) required at maximum flow with available pressure drop. Undersizing causes insufficient capacity. Oversizing leads to unstable operation where the valve hunts—oscillating around setpoint rather than settling smoothly.

Comparing Flow Valve Types: Technical Parameters

Understanding the performance characteristics that differentiate flow valve types helps match capabilities to application requirements. The following table synthesizes key engineering parameters based on API, ASME, and ISO standards:

| Valve Type | Pressure Drop (Cv Efficiency) | Shutoff Class (API 598) | Throttling Capability | Rangeability | Actuation Torque |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gate Valve | Very Low (Highest Cv) | Excellent (Rate A) | Poor - Not Recommended | N/A | High (Multi-turn) |

| Globe Valve | High (Low Cv) | Excellent (Rate A) | Excellent | 50:1 to 100:1 | Very High |

| Ball Valve (Full Port) | Very Low (Highest Cv) | Excellent (Zero Bubble) | Poor (Standard), Excellent (V-Port) | 300:1 (V-Port) | Low (Quarter-turn) |

| Butterfly Valve (TOBV) | Low (High Cv) | Excellent (Rate A) | Moderate | 30:1 to 50:1 | Very Low |

| Diaphragm Valve (Weir) | Moderate | Good | Good | 40:1 | Moderate |

| Needle Valve | Very High (Lowest Cv) | Excellent | Excellent (Low Flow) | 100:1+ | Low (Fine Thread) |

The flow coefficient (Cv) deserves additional explanation because it is the fundamental sizing parameter. Cv is defined as the flow rate in gallons per minute (GPM) of 60°F water that produces a 1 psi pressure drop across the valve. A higher Cv means less resistance. For example, a full-bore ball valve might have a Cv of 500 for a 4-inch size, while a globe valve of the same size might only achieve Cv of 150 due to its tortuous internal path.

The relationship between Cv and flow for incompressible liquids follows the equation:

Where Q is flow in GPM, SG is specific gravity (water = 1.0), and ΔP is pressure drop in psi. This formula reveals that doubling the Cv reduces required pressure drop by a factor of four for the same flow rate. In systems where pumping energy is expensive, selecting a valve type with higher Cv delivers long-term cost savings despite potentially higher initial valve cost.

For compressible fluids (gases and steam), the calculation becomes more complex. An expansion factor (Y) must be applied to account for density change as the gas accelerates through the valve restriction. The factor varies with pressure ratio (P2/P1) and approaches choked flow conditions when the downstream pressure drops below the critical pressure ratio.

Selecting the Right Flow Valve Type for Your Application

Proper valve selection requires analyzing multiple factors beyond just pipe size and pressure rating. The selection methodology professional engineers use can be remembered through the acronym STAMPED:

The STAMPED Methodology

- Size: Pipe diameter and flow capacity needed.

- Temperature: Fluid extremes and ambient conditions.

- Application: Isolation vs. Throttling.

- Material: Compatibility with corrosive or abrasive fluids.

- Pressure: Operating range and design limits.

- Ends: Connection type (flanged, threaded, welded).

- Delivery: Lead time and availability.

Application Analysis comes first. Is the valve performing isolation service (on/off) or modulating control (throttling)? Isolation applications prioritize tight shutoff and low pressure drop, pointing toward gate valves or full-bore ball valves. Modulating control demands predictable flow characteristics across a wide range, favoring globe valves or characterized ball valves.

The fluid properties shape material and design selection. Viscous fluids exceeding 1000 centipoise struggle with complex internal passages, making full-bore designs preferable. Abrasive slurries containing suspended solids rapidly destroy precision-machined seats, requiring either sacrificial soft seats (in diaphragm valves) or hardened metal components with large clearances (in plug valves).

Temperature extremes eliminate entire valve families. Above 800°F, elastomer-sealed designs fail, limiting choices to metal-seated gate, globe, or triple-offset butterfly valves. Below -50°F in cryogenic service, material toughness becomes critical. Standard carbon steel undergoes ductile-to-brittle transition, mandating special low-temperature materials like ASTM A352 LCB steel or austenitic stainless steel per ASME B16.34.

Cavitation risk must be quantified using the cavitation index sigma:

Where P1 is inlet pressure, Pv is vapor pressure of the liquid, and ΔP is pressure drop. When sigma falls below 1.0, cavitation damage becomes severe. The solution involves either reducing pressure drop by oversizing the valve (increasing Cv), installing a multi-stage trim that divides the pressure drop across several restrictions, or selecting a valve design less prone to cavitation like an eccentric rotary valve.

Corrosion resistance requirements derive from the chemical compatibility table in NACE MR0175 for sour service (H2S-containing fluids) or material selection per ISO 15156. In seawater applications, standard 316 stainless steel suffers pitting corrosion. Super duplex stainless steel (UNS S32750) with a pitting resistance equivalent number (PREN) exceeding 40 becomes mandatory. For hydrofluoric acid service, only Monel 400 nickel-copper alloy provides adequate resistance.

The installed flow characteristic differs from the inherent characteristic tested in a laboratory. Real systems have pipeline pressure drop that varies with flow rate. An equal percentage valve compensates for this system effect. At low flow, where system pressure drop is minimal, the valve provides small incremental changes. At high flow, where system pressure drop consumes available differential, the valve provides large changes to maintain linear installed response. This principle explains why 70% of industrial control valves use equal percentage trim despite linear trim being simpler to manufacture.

Actuator selection connects to valve type. Multi-turn valves (gate, globe) traditionally use electric motor operators for automated service. Quarter-turn valves (ball, butterfly) suit pneumatic rack-and-pinion or scotch-yoke actuators that deliver high breakaway torque. The 2025 industry trend favors electric actuators even for rotary valves because compressed air systems suffer energy losses from leakage, whereas electric actuators only consume power during movement. Smart electric actuators with integrated digital positioners enable predictive maintenance through stem friction monitoring, a capability pneumatic systems cannot match.

Industry-Specific Flow Valve Applications

Different industries impose unique requirements that favor specific flow valve types.

Petroleum refining operates under API 600, API 602, and API 608 standards. High-temperature, high-pressure hydrocarbon service with potential hydrogen sulfide content demands gate valves and globe valves in ASTM A216 WC9 chrome-moly steel. Fugitive emissions regulations per EPA Method 21 require low-emission packing designs with graphite filament or PTFE V-ring configurations maintaining less than 500 ppm hydrocarbon leakage.

Water and wastewater treatment emphasizes corrosion resistance and large flow capacity at low head loss. Resilient-seated butterfly valves dominate this sector because their cost per unit Cv is lower than any alternative in sizes 6 inches and above. For drinking water, valves must meet NSF/ANSI 61 standards certifying materials do not leach harmful substances. Ductile iron bodies with fusion-bonded epoxy coating provide decades of buried service life.

Pharmaceutical manufacturing under FDA 21 CFR Part 211 requires sanitary design preventing contamination. Diaphragm valves meeting ASME BPE standards with electropolished surfaces below 15 microinches Ra dominate. All wetted components must have material certifications tracing to heat lot. Validation protocols require documented clean-in-place (CIP) and steam-in-place (SIP) testing proving the valve achieves sterility assurance level (SAL) of 10^-6.

Natural gas transmission pipelines use trunnion ball valves per API 6D with full-bore passages allowing pig passage. Fire-safe testing per API 607 simulates fire exposure, verifying the valve maintains pressure boundary integrity after soft seats burn away, preventing catastrophic gas release. Double block and bleed (DBB) capability allows safe maintenance isolation.

Steam systems in power generation and district heating require valves handling 600°F to 1000°F superheated steam. Globe valves with pressure-balanced plug designs reduce actuator thrust requirements. The pressure drop they create actually benefits steam systems by reducing velocity and preventing erosive cutting at downstream piping elbows. For modulating temperature control through desuperheating, high-rangeability characterized globe valves provide stable operation from 5% to 100% load.

Cryogenic service in LNG facilities and industrial gas plants handles fluids below -150°F. Extended bonnet designs position the packing gland far from the cold zone, preventing packing freeze-up. Materials like ASTM A352 LCC steel and 304L stainless steel maintain impact toughness at these temperatures. Liquid oxygen valves require oxygen cleaning per ASTM G93, removing all traces of hydrocarbons to prevent ignition under enriched oxygen conditions.

Maintenance Considerations and Total Cost of Ownership

The initial purchase price of a flow valve represents only 20-30% of its total lifecycle cost. Maintenance frequency, spare parts availability, and mean time between failures drive the economic equation.

Gate valves have the lowest initial cost but highest maintenance burden. The rising stem design with external threads requires periodic lubrication. Backseat function must be verified during overhaul to allow packing replacement under pressure. Once gate seating surfaces show wire drawing from improper throttling use, restoration requires costly machining or replacement.

Globe valves offer easy maintenance access because the bonnet design allows dropping the internals out through the top without removing the valve body from the pipeline. Trim components are standardized and interchangeable. A single valve body can accommodate multiple trim configurations, from cavitation-resistant multi-stage designs to high-capacity low-noise trims. This modularity delivers flexibility as process requirements evolve.

Ball valves minimize maintenance due to their simple design with few moving parts. However, once the ball surface or seats show wear, field repair is impractical. Trunnion-mounted designs allow seat replacement in-situ, but floating ball valves typically require complete valve replacement. For critical isolation service, specifying metal-seated ball valves provides longer service intervals at higher initial cost.

Butterfly valves, especially triple-offset designs, are revolutionizing maintenance economics. The metal-to-metal seating makes no contact until final closure, eliminating continuous rubbing wear. Service life reaches 100,000 cycles compared to 10,000 cycles for resilient-seated designs. In pipeline applications above 16-inch diameter, the weight savings translate to reduced crane requirements during maintenance outages.

Predictive maintenance programs using digital valve controllers with embedded diagnostics fundamentally change the maintenance paradigm. Rather than scheduled overhauls every 12 months, condition-based maintenance responds to actual valve health. Stem friction trending detects packing degradation months before external leakage occurs. Cycle counting predicts seat wear based on operational history rather than calendar time. These capabilities reduce maintenance costs by 40% while simultaneously improving reliability.

Conclusion

Selecting among flow valve types requires engineering analysis that balances fluid dynamics, materials science, operational requirements, and economic factors. No single valve type excels in all criteria. Gate valves offer unmatched flow capacity and tight shutoff but fail in throttling service. Globe valves provide superior modulating control at the cost of high pressure drop and actuation force. Ball valves deliver speed and simplicity but limited mid-range control unless specifically configured with characterized trim. Butterfly valves optimize size and weight but require careful attention to flow-induced vibration in partially open positions.

The decision framework starts with defining the primary function—isolation or control. Next, analyze the fluid properties including corrosivity, viscosity, and potential for cavitation or flashing. Match these requirements against valve capabilities documented in relevant standards like API 600, ISO 5208, and ASME B16.34. Calculate the required Cv using system hydraulics and verify the selected valve can operate within its optimal rangeability.

Modern industrial practice increasingly favors electric actuation for automated flow valve types, driven by energy efficiency and diagnostic capabilities. Digital valve controllers with HART or FOUNDATION Fieldbus communication enable integration into industrial IoT platforms, transforming valves from passive components into intelligent assets that predict their own failures and optimize process control.

The most reliable valve selection comes from understanding that application-specific knowledge matters more than generic performance claims. A valve that performs flawlessly in clean water service may fail catastrophically in sour gas or slurry applications. Successful engineering demands matching valve internal geometry, materials, and actuation to the specific thermal, chemical, and mechanical stresses the system imposes. This analysis-driven approach, rather than lowest-price purchasing, delivers the lowest total cost of ownership and highest operational reliability.