A pressure relief valve stands as the last line of defense in any pressurized system. When this critical safety component fails, the consequences range from minor operational inefficiencies to catastrophic equipment destruction. Understanding what happens when a pressure relief valve malfunctions helps facility managers and maintenance teams recognize problems before they escalate into dangerous situations.

The impact of a failing pressure relief valve depends entirely on how it fails. These valves can stick closed and trap dangerous pressure inside vessels, or they can stick open and bleed off system pressure continuously. They can also develop partial failures that cause equipment wear, energy waste, and environmental violations. Each failure mode creates distinct symptoms and requires different responses.

The Two Primary Failure Modes

Pressure relief valves fail in fundamentally different ways, and recognizing which type of failure you're dealing with determines the urgency of your response.

Stuck Closed: The Silent Killer

When a relief valve sticks in the closed position, it stops performing its safety function entirely. The valve becomes physically unable to open even when system pressure exceeds safe limits. This represents the most dangerous failure scenario because it provides no warning until pressure reaches critical levels.

Several physical mechanisms cause valves to stick closed. Corrosion between the disc and seat can create a metallurgical bond strong enough to prevent opening. Foreign material lodged in the guide sleeve blocks the disc from lifting. In some cases, shipping restraints installed by manufacturers remain attached during commissioning, physically locking the valve shut. Paint overspray during facility maintenance can seal moving parts together. These seemingly minor issues transform a safety device into a liability.

The thermodynamic consequences of a stuck-closed valve are severe. In a closed system with continued energy input, pressure builds without limit until something fails. Consider a steam boiler where the burner continues firing but the safety valve cannot open. Water at 300°F under pressure contains enormous stored energy. When vessel walls finally rupture, that superheated water instantly flashes to steam, expanding roughly 1,600 times in volume within milliseconds. The resulting explosion generates supersonic shock waves capable of leveling buildings and propelling metal fragments hundreds of feet.

Industrial accident investigations consistently reveal stuck-closed valves as contributing factors in catastrophic failures. The American Petroleum Institute standard API 576 classifies this failure mode as requiring immediate corrective action because detection typically occurs only during actual overpressure events.

Stuck Open: The Continuous Bleed

A valve stuck in the open position creates an entirely different problem set. Instead of trapping pressure, it continuously vents process media regardless of system conditions. The valve either fails to reseat after opening or becomes physically jammed in the discharge position.

This failure mode announces itself clearly through persistent noise from the discharge line and inability to maintain system pressure. However, operators sometimes misdiagnose the problem because control panels may indicate the valve received a close command without confirming actual disc position. The Three Mile Island nuclear accident in 1979 demonstrated this diagnostic gap with devastating consequences. A pilot-operated relief valve stuck open while control room instruments showed only that closing signals had been sent. Operators shut down emergency cooling systems based on false information while thousands of gallons of coolant escaped through the jammed valve, leading to partial core meltdown.

In industrial compressed air systems, a stuck-open relief valve prevents the compressor from reaching its cutout pressure. The machine runs continuously at full load instead of cycling normally. This forces the motor into thermal overload conditions, carbonizes lubrication oil, and accelerates wear on piston rings and valve plates. Within days or weeks, a compressor that should have lasted years suffers catastrophic mechanical failure.

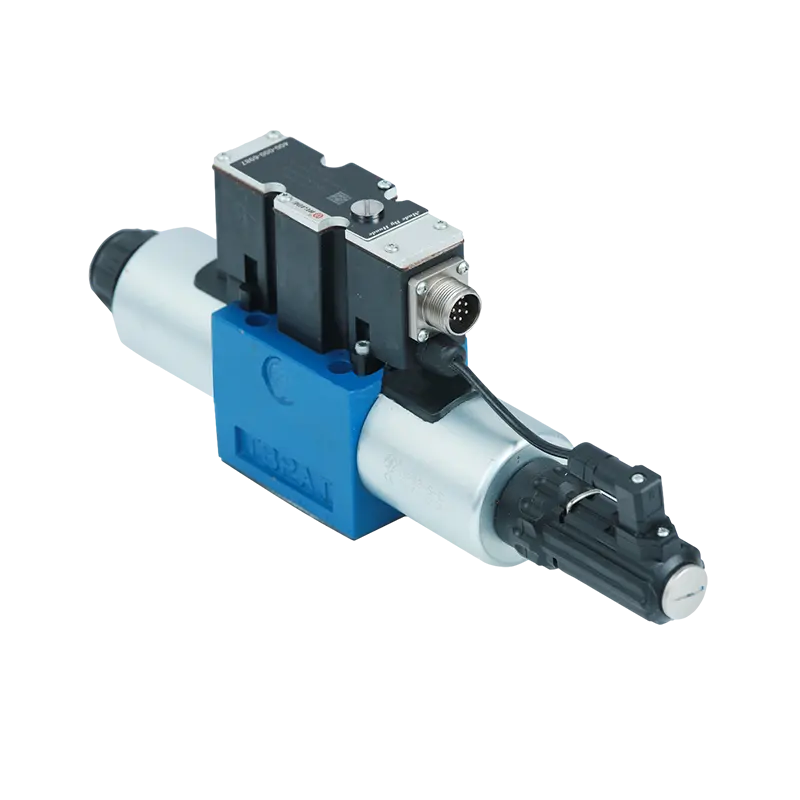

Hydraulic systems experience a different consequence when their pressure relief valves fail open. The hydraulic pump continues generating flow, but instead of powering actuators, all flow dumps directly back to the reservoir through the stuck valve. The throttling action converts hydraulic pressure into heat at a dramatic rate. Oil temperature climbs rapidly, degrading seals and lubricating properties. If uncorrected, the thermal buildup can seize the pump entirely.

The economic impact of continuous venting is quantifiable and substantial. Using the Napier formula for steam systems, a half-inch opening at 100 psig pressure wastes approximately $84,000 annually in fuel and water treatment costs at typical industrial utility rates. This calculation excludes downtime expenses and equipment damage from pressure starvation.

Intermediate Failure States

Not all valve failures are binary. Several partial malfunction modes create ongoing problems without completely eliminating valve function.

Chattering: High-Frequency Mechanical Destruction

Chattering occurs when a relief valve rapidly oscillates between open and closed positions, sometimes cycling dozens of times per second. This violent behavior stems from fluid dynamics issues rather than mechanical jamming. Two primary causes trigger chattering: oversized valve selection and excessive inlet pressure drop.

When a valve's rated capacity far exceeds actual system relief requirements, opening the valve instantly drops system pressure below the reseating point. The valve slams shut, pressure immediately rebuilds, and the cycle repeats. Each cycle subjects the disc and seat to impact forces similar to a forging hammer. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers standard ASME Section I limits inlet line pressure loss to three percent of set pressure specifically to prevent this phenomenon.

The mechanical consequences of sustained chattering are catastrophic. Precision-machined sealing surfaces deform and crack under repeated impacts. Bellows-type backpressure valves develop metal fatigue cracks in their flexible elements, releasing process media to atmosphere. Mounting flanges work loose as vibration propagates through connected piping. In documented cases, chattering has caused complete valve disintegration and pipeline fractures within hours.

Simmering: The Environmental Time Bomb

Simmering describes continuous low-level leakage when system pressure approaches but does not exceed the valve set point. This typically occurs when operating pressure runs at 95 to 98 percent of relief pressure, or when valve springs have relaxed over time through thermal creep.

Process fluid escaping through microscopic gaps between disc and seat travels at extremely high velocity. When this flow contains particulates or occurs in corrosive service, it creates wire drawing erosion. The phenomenon resembles waterjet cutting, progressively carving grooves into sealing surfaces. Once wire drawing initiates, leak rates increase exponentially and the damage becomes irreversible without parts replacement.

From a regulatory perspective, simmering represents a significant compliance risk. Environmental Protection Agency data indicates that valves contribute approximately 60 percent of fugitive emissions from industrial facilities, with relief valves representing a substantial portion because they typically discharge directly to flare systems or atmosphere. Continuous releases of volatile organic compounds trigger Clean Air Act violations and associated penalties. The leaked material also represents direct product loss measurable in thousands of dollars annually per valve.

| Failure Mode | Root Mechanism | Primary System Effect | Observable Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stuck Closed | Corrosion bonding, debris, shipping restraints | Catastrophic rupture/explosion | None (Silent failure) |

| Stuck Open | Debris on seat, guide seizure, pilot malfunction | System depressurization | Loud noise, low pressure |

| Chattering | Oversized valve, inlet pressure drop >3% | Mechanical destruction | Violent vibration |

| Simmering | Pressure near set point, spring relaxation | Fugitive emissions, erosion | Hissing, ultrasonic noise |

Physical Root Causes

Understanding why pressure relief valves fail requires examining the metallurgical, chemical, and mechanical degradation processes that occur during service life.

[Image of corroded pressure relief valve internal components] Corrosion and Stress Corrosion CrackingCorrosion attacks relief valves through multiple pathways. Uniform corrosion gradually reduces wall thickness in wetted components. Pitting corrosion creates localized deep cavities that destroy sealing surface flatness. Galvanic corrosion occurs at dissimilar metal junctions when proper isolation was not maintained during assembly.

The most insidious corrosion mechanism is stress corrosion cracking. This phenomenon requires three simultaneous conditions: a susceptible material, a corrosive environment, and tensile stress. Austenitic stainless steel springs exposed to chloride-containing atmospheres in coastal facilities commonly experience SCC. The cracks propagate slowly until sudden brittle fracture occurs. When a spring fails, the valve loses all set pressure control and may open at pressures far below design intent or fail to open at all depending on fracture location.

Hydrogen sulfide environments in sour gas service cause sulfide stress cracking in carbon steel components. This form of environmental cracking can occur at stress levels well below normal design allowances. Industry standards like NACE MR0175 specify resistant materials for these applications, but many failures result from installing inappropriate valve metallurgy in corrosive service.

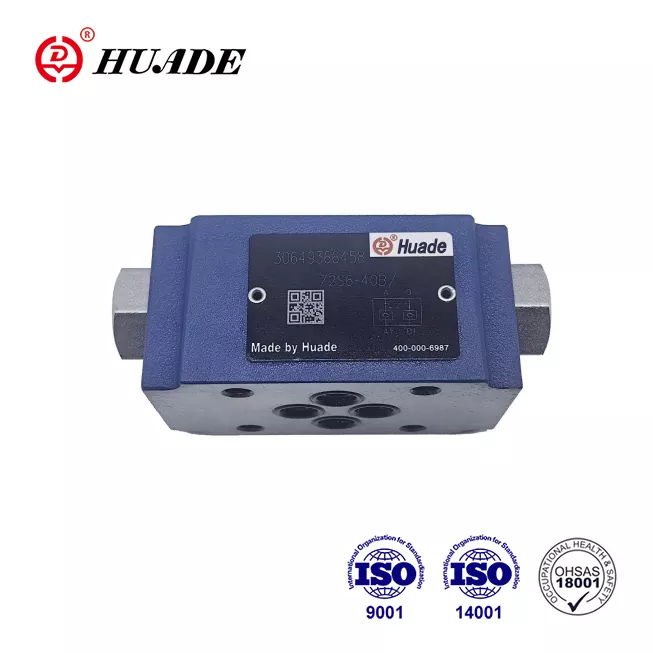

Spring DegradationValve springs operate under constant compression in elevated temperature environments. Over years of service, the spring material experiences creep, a time-dependent deformation under sustained load. Metallurgically, dislocations in the crystal structure gradually migrate and rearrange. The practical result is permanent reduction in spring stiffness, a phenomenon called spring relaxation or set loss.

A valve originally set to open at 150 psig might open at 140 psig after five years of service due to spring relaxation. This set point drift causes premature opening and process upsets. Conversely, if corrosion products accumulate on spring coils or between the spring and its housing, effective spring rate increases and the valve opens at pressures above its certified set point.

Temperature accelerates spring degradation exponentially. Springs operating at 400°F degrade roughly twice as fast as identical springs at 200°F. The ASME code recognizes this by requiring more frequent testing intervals for high-temperature applications.

Human Error and Maintenance MalpracticeMany valve failures trace directly to human mistakes during installation or maintenance. Large valves are shipped with gag devices that mechanically lock the disc to prevent damage during transport. Installation procedures require removing these restraints, but oversight occurs with alarming frequency. A valve with shipping restraints still attached provides zero overpressure protection despite appearing normal externally.

Improper lubrication practices cause numerous failures. Some maintenance personnel apply general-purpose oils or greases to valve stems without checking compatibility. Certain lubricants polymerize at elevated temperatures, creating sticky residues that increase breakaway force. Other lubricants attract and hold particulates, forming an abrasive compound that accelerates wear.

Paint contamination represents a recurring problem during facility maintenance painting campaigns. Overspray enters the valve bonnet and coats sliding surfaces. When paint cures, it bonds moving parts together. Studies have measured opening pressure increases exceeding 50 percent due to paint contamination alone. Proper procedures require bagging or removing relief valves before nearby painting operations begin.

Application-Specific Consequences

The impact of valve failure varies significantly depending on the system type and process media involved.

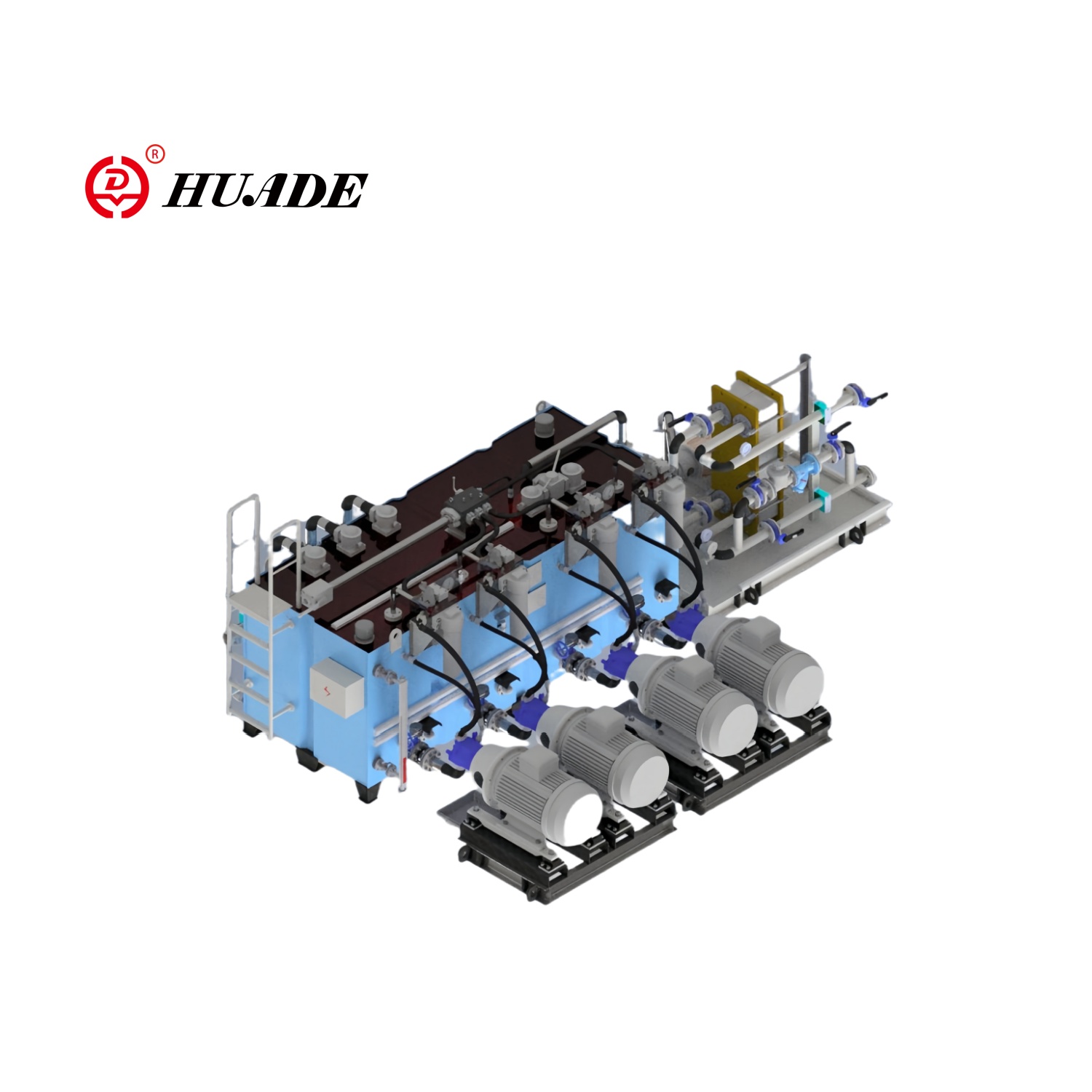

ASME Section I boiler code imposes strict requirements on power boiler safety valves. Section I valves must incorporate dual adjusting rings to achieve tight blowdown control. Installing a Section VIII valve on a boiler creates a code violation and a safety hazard. Section VIII valves lack the internal trim geometry to provide adequate relieving capacity and proper reseating characteristics for boiler service.

Steam leak economics are particularly harsh. A relatively small quarter-inch diameter leak at 100 psig pressure wastes approximately 240 pounds of steam per hour. Annualized at $10 per thousand pounds of steam, this single leak costs $21,000 yearly. Larger leaks scale geometrically rather than linearly because increased orifice area allows higher velocity and mass flow.

[Image of industrial steam boiler safety valve installation]Hydraulic Systems

Hydraulic relief valves serve dual roles as both safety devices and pressure regulators. When a hydraulic relief valve sticks open, the entire pump output flows directly across the valve back to the reservoir. The energy equation for this condition shows that all pump input power converts to heat in the fluid. A 20-horsepower pump running at full displacement with its relief valve stuck open adds approximately 50,000 BTU per hour to the hydraulic oil. Elevated oil temperature triggers a cascade of problems, from viscosity decrease to seal failure.

Residential Water Heater Safety

Temperature and pressure relief valves (T&P valves) protect against both overpressure and overtemperature. When a T&P valve fails closed, a malfunctioning thermostat can heat water well beyond boiling point under pressure. If the tank then ruptures, the superheated water flashes instantly to steam with explosive force. Despite their small size, failed residential water heaters have destroyed homes and caused fatalities.

Compressed Air Systems

Compressed air storage vessels contain substantial elastic potential energy. If a vessel ruptures due to relief valve failure, this energy releases as a combination of shock wave and fragment kinetic energy. A less dramatic but economically significant consequence occurs when a compressed air safety valve fails open or leaks. The compressor cannot build sufficient pressure to reach its automatic shutoff point, forcing the unit into continuous operation, costing thousands in excess electricity.

Regulatory Framework and Legal Liability

Operating equipment with defective pressure relief valves violates multiple regulatory standards and creates substantial legal exposure.

OSHA Process Safety ManagementThe Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulates pressure relief systems primarily through its Process Safety Management standard, 29 CFR 1910.119. This rule applies to facilities handling threshold quantities of hazardous chemicals and requires written programs for mechanical integrity. Common citations include failure to follow recognized and generally accepted good engineering practices (RAGAGEP).

Standards and Code ComplianceASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code establishes design requirements. Valves must bear appropriate code stamps (V or UV). The National Board of Boiler and Pressure Vessel Inspectors maintains a VR stamp program for repair organizations. Organizations performing valve maintenance without proper certification violate ASME requirements.

Liability ConsiderationsProduct liability law treats pressure vessel explosions under strict liability principles. Plaintiffs need not prove negligence; demonstrating that a defective safety device contributed to the accident establishes liability. Documented evidence that the facility failed to implement a valve testing program per recognized standards dramatically strengthens plaintiff cases.

| Leak Diameter | Steam Loss Rate (lb/hr) | Annual Cost (USD) | Operational Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/16 inch | 15 | $1,300 | Minor efficiency loss |

| 1/8 inch | 60 | $5,200 | Noticeable cost increase |

| 1/4 inch | 240 | $21,000 | Significant financial drain |

| 1/2 inch | 960 | $84,000 | Major asset loss |

Modern Diagnostic Approaches

Detecting valve degradation before functional failure requires moving beyond calendar-based testing to condition monitoring.

In-Line Testing TechnologyTraditional valve testing requires removal and bench testing, which introduces risks. In-line testing systems verify valve function while installed and under operating pressure. Hydraulic lift assist devices attach to the valve bonnet and apply controlled force. Precision pressure transducers monitor inlet pressure while the lifting force gradually increases, calculating the actual opening pressure without full blowdown.

Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) IntegrationModern facilities deploy wireless sensor networks. WirelessHART pressure transmitters track pressure differentials indicating valve opening. Acoustic sensors enable trending analysis, where machine learning algorithms establish baseline signatures. Deviations flag developing problems like simmering or partial lifts.

Conclusion

Pressure relief valve failure transforms a safety device into a liability through mechanisms ranging from explosive rupture to insidious economic bleeding. The stuck-closed failure mode represents an existential threat where detection occurs only during the catastrophic event the valve was installed to prevent. The stuck-open condition creates a different but substantial problem: continuous loss of process media, equipment damage from pressure starvation, and potential environmental violations.

Forensic analysis of failed valves consistently reveals that most failures result not from random mechanical breakdown but from predictable degradation processes: corrosion accumulation, improper valve selection, inadequate maintenance programs, and human error during installation or service. Mitigating these risks requires rigorous adherence to ASME and API standards, implementation of risk-based inspection programs, and adoption of modern diagnostic technologies including acoustic monitoring and in-line testing.

The regulatory framework surrounding pressure relief systems imposes clear legal obligations. Failure to meet these requirements not only jeopardizes personnel safety but creates substantial legal exposure. In high-pressure industrial systems, the pressure relief valve functions as the final barrier between controlled operation and catastrophic failure. The cost of comprehensive valve reliability programs pales compared to the consequences of catastrophic failure: facility destruction, environmental contamination, regulatory enforcement, and loss of human life.