When fluid pressure builds up beyond safe limits in hydraulic systems, boilers, or process equipment, something has to give. That's where pressure relief valves come in - they're your system's last line of defense against catastrophic failure. But walk into any industrial supply catalog and you'll find dozens of valve types, each designed for specific conditions. Choosing the wrong type doesn't just waste money; it can compromise safety.

This guide breaks down the major pressure relief valve types you'll encounter, explaining how each works and when to use them. Whether you're designing a new hydraulic circuit or replacing an existing valve, understanding these differences matters.

How Pressure Relief Valves Actually Work

Before diving into specific types, let's establish the basic principle. Every pressure relief valve operates on force balance. The valve stays closed when the closing force (usually from a spring) exceeds the opening force from system pressure acting on the valve disc area.

[Image of pressure relief valve force balance diagram]The fundamental equation is straightforward:

When system pressure rises high enough, the opening force overcomes the spring force, and the valve opens to discharge fluid. Once pressure drops sufficiently, the spring pushes the disc back onto its seat, stopping the flow.

This simple concept gets complicated quickly when you factor in different fluid types, backpressure effects, and application requirements. That's why we have distinct valve types.

Spring-Loaded Direct-Acting Valves: The Industry Workhorse

Spring-loaded valves are the most common type you'll see in industrial applications. A helical spring sits above the valve disc, providing the closing force. As inlet pressure increases, it compresses the spring until the disc lifts off its seat.

Conventional Spring-Loaded Valves

These are the basic design. The bonnet (cap) housing the spring vents to the outlet side of the valve. This simple arrangement works fine in many applications, but it has a critical limitation.

Backpressure - any pressure on the outlet side - acts on the back of the valve disc, adding to the closing force. This means:

If backpressure varies (common when multiple valves discharge into a shared header), the valve's actual opening pressure shifts. API 520 standards limit conventional valves to applications where backpressure stays below 10% of set pressure for this reason.

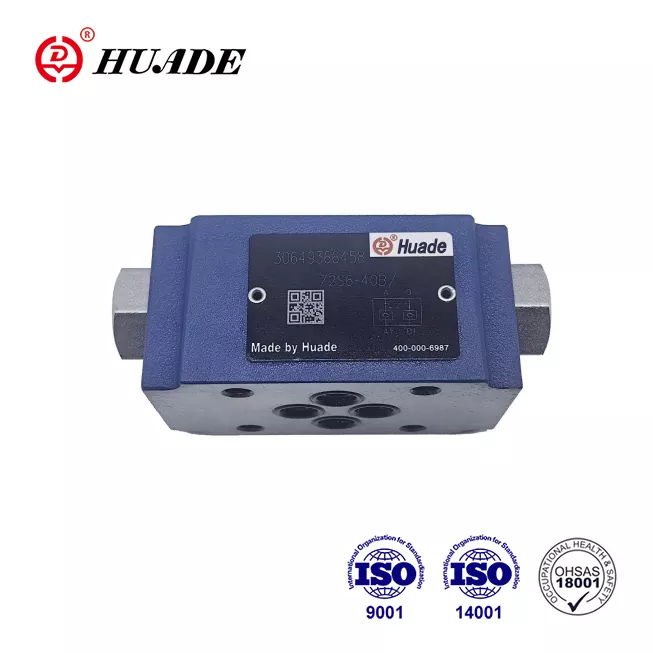

Balanced Bellows Valves: Fighting Backpressure

To overcome backpressure sensitivity, engineers developed balanced bellows designs. A flexible metal bellows wraps around the valve stem, sealing off the bonnet from process fluid. The bellows effective area matches the seat area.

Here's the clever part: backpressure pushes down on the disc back but simultaneously pushes up on the bellows bottom. Since both areas are equal, these forces cancel out:

This design handles backpressure up to 30-50% of set pressure without affecting valve performance.

| Feature | Conventional | Balanced Bellows |

|---|---|---|

| Backpressure Limit | 10% of set pressure | 30-50% of set pressure |

| Design Complexity | Simple, fewer parts | Bellows adds complexity |

| Cost | Lower | Higher (15-30% premium) |

| Maintenance Risk | Lower | Bellows fatigue/rupture |

| Typical Application | Standalone systems | Common discharge headers |

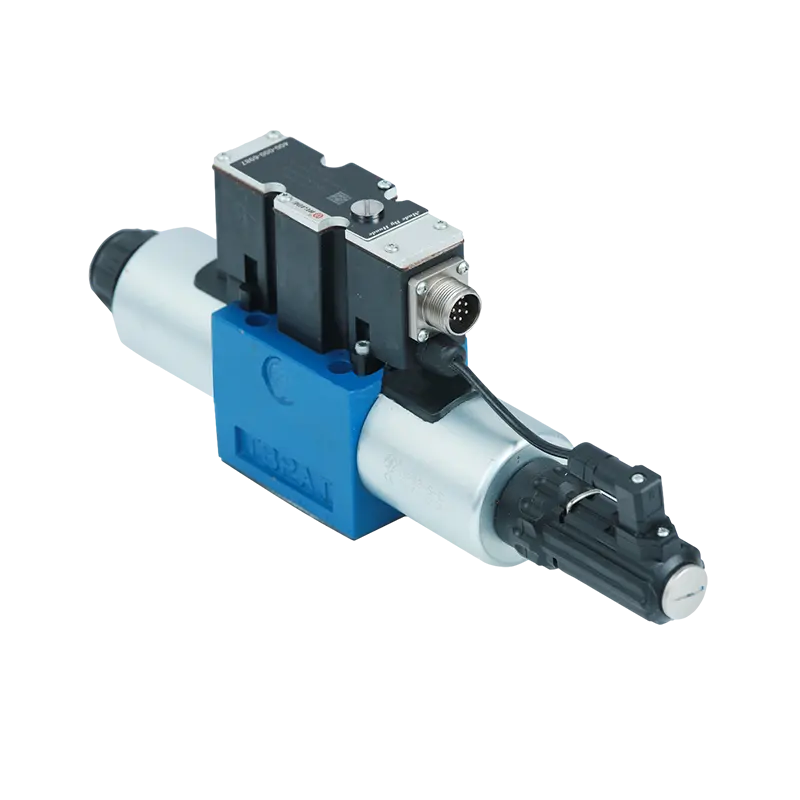

Pilot-Operated Relief Valves: Precision Under Pressure

When you need tight control or face extreme conditions (very high pressure, large flow rates, or highly unstable backpressure), spring-loaded valves hit their limits. Springs get too large and unwieldy. That's where pilot-operated relief valves (PORV) shine.

[Image of pilot operated relief valve schematic]The Reverse Sealing Principle

A PORV consists of a main valve (usually piston-type) and a small pilot valve. The magic lies in area differential. The piston top (dome area) is 30-50% larger than the bottom (seat area). System pressure fills the dome chamber through a connecting tube.

$$F_{opening} = P_{system} \times A_{seat}$$

Since dome area exceeds seat area, closing force always wins - as long as dome pressure equals system pressure. The valve seals tighter as pressure increases, the opposite of spring-loaded valves where seal compression decreases near set pressure.

Pop-Action vs Modulating Pilots

Pilot valves come in two control philosophies:

- Pop-action pilots: Snap fully open when set pressure is reached. Mimics conventional safety valve behavior for gas services requiring rapid pressure relief.

- Modulating pilots: Crack open proportionally to overpressure. Essential for liquid line protection to prevent water hammer.

Flowing vs Non-Flowing Design

Flowing-type pilots allow process fluid to pass through the pilot mechanism, which can clog if fluids are dirty. Non-flowing designs route process fluid away from the pilot, making them excellent for dirty services like crude oil or natural gas with entrained liquids.

Safety Valves vs Relief Valves: The Fluid Matters

You'll often hear these terms used interchangeably, but ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code makes a clear distinction based on fluid compressibility.

Designed for pop-action behavior. When set pressure is reached, the valve snaps to full open position within milliseconds. Why? Gases expand rapidly. A gradual opening might not relieve pressure fast enough to prevent runaway expansion.

Relief Valves for Incompressible Fluids (Liquids)

Designed for modulating opening. The disc lifts gradually proportional to pressure. This prevents water hammer - the destructive pressure surge caused by suddenly stopping or starting liquid flow.

ASME Section I vs Section VIII: Why the Code Matters

Not all pressure relief valves meeting ASME standards are interchangeable.

- ASME Section I (Boilers): For fired steam boilers >15 psig. "V" stamp. Overpressure max 3%. Priority: preventing explosion while conserving steam.

- ASME Section VIII (Pressure Vessels): For reactors, tanks, exchangers. "UV" stamp. Overpressure max 10%. Priority: handling diverse process fluids.

Selecting by Application: Real-World Scenarios

Blocked DischargeA pump runs with its outlet closed. The valve must handle the pump's full flow capacity. This often governs size selection for liquids.

External FireHeat causes liquid to boil rapidly. The expanding vapor requires enormous relief capacity. Fire scenarios frequently determine the largest required orifice size.

Thermal ExpansionLiquid trapped in pipes heats up (solar/trace heating). Even a few degrees causes massive pressure rise. A small relief valve is essential here.

Installation & Failure Modes

Inlet Piping and the 3% Rule

API 520 states inlet piping pressure drop should not exceed 3% of set pressure to prevent chatter. Chatter is a violent cycle where the valve opens, inlet pressure drops due to friction, the valve slams shut, pressure builds, and it opens again. This damages seating surfaces and flanges rapidly.

Common Failure Modes

- Leakage/Simmer: Dirt trapped on the seat or operating too close to set pressure (wire-drawing).

- Chatter: Oversizing or excessive inlet pressure drop.

- Stuck Shut: Corrosion or polymerized fluids gluing components together.

- Bellows Rupture: Fatigue failure exposing springs to corrosive fluids.

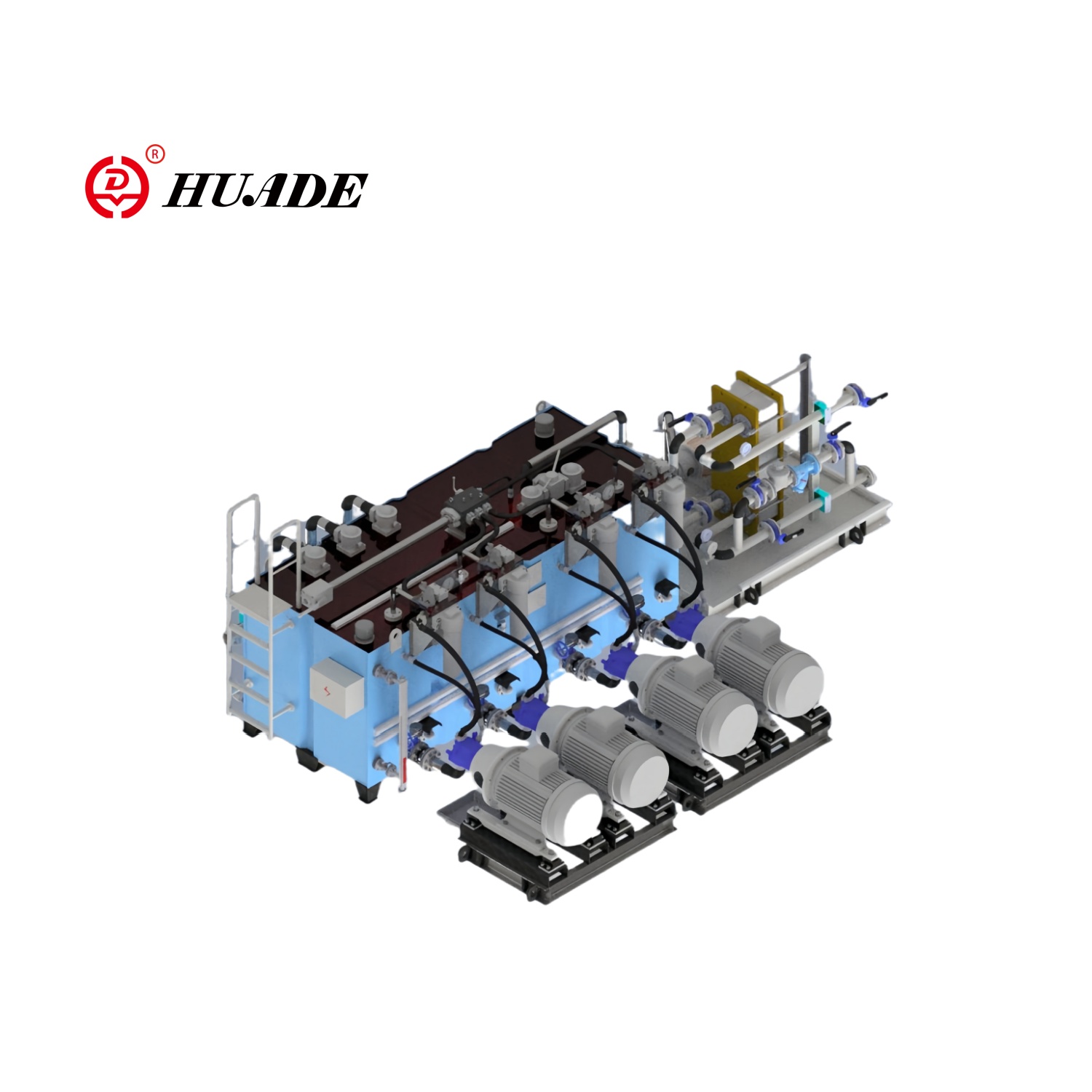

Maintenance & Smart Monitoring

Testing Strategies

- Bench Testing: Remove valve and test in shop. Requires shutdown.

- In-Situ Testing: Use hydraulic assist equipment to test while installed. Verifies set pressure but not discharge capacity.

Emerging Tech: Smart Monitoring

Wireless Acoustic Sensors: Detect ultrasonic frequencies from leakage, providing instant alerts.

Bellows Monitoring: A pressure transmitter at the bonnet vent warns of bellows rupture, converting reactive maintenance to predictive.

Conclusion

Pressure relief valves represent mature technology, but selecting the wrong type causes problems ranging from nuisance leakage to catastrophic damage. Take time to analyze your operating conditions—especially backpressure and fluid type—and match valve characteristics to your actual requirements.